· 8 min read

Survey shows Nebraska U among best in energy consumption, costs

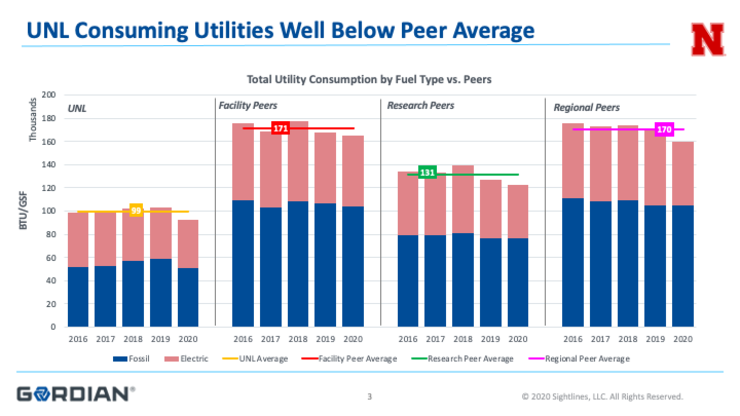

A sustainability focus led by Facilities, Maintenance and Operations employees is saving millions of dollars annually and holding the University of Nebraska-Lincoln’s energy consumption lower than that of its peer institutions.

According to an annual review by third-party consultant Gordian, the University of Nebraska–Lincoln’s electric and fossil fuel consumption is lower than comparable peer institutions, including other Big Ten partners. Facilities, Maintenance and Operations Energy Services accomplished this through its dedication to providing safe, smart, reliable spaces for the university to accomplish its teaching and research missions by being sustainable, economical, reliable and resilient.

Gordian is a data, software and services company that partners with over 450 colleges and universities across the country to provide an analytical framework that measures the current position and operational performance relative to peer institutions.

Energy Services, which consists of close collaboration between Utility Services and Building Systems Maintenance, works to consistently improve energy efficiency through a layered approach — which has ranged from manufacturing its own room controls and developing a centralized energy system, to developing a technically complex facilities system and investing in energy storage.

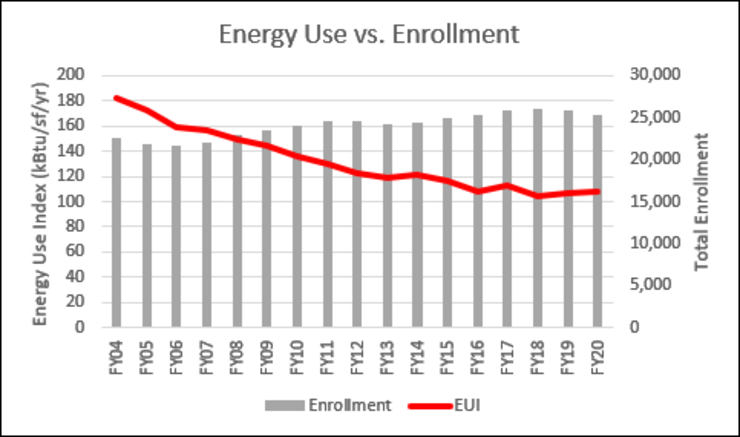

While enrollment and research expenditures have grown on campus, the work has improved the university’s energy efficiency by 40% since 2004. The university’s energy-saving measures combined for an avoided cost of $9 million in 2020. Overall, the measures saved more than $85 million in the past 17 years, said Kirk Conger, mechanical engineer and energy projects manager for building systems maintenance.

“Those savings remove some budget pressure from other university departments, leading to advancement in other programs and facilities,” Conger said.

Smart investments

To reach these levels of efficiency, “we have invested in higher efficiency equipment over the last 20 years,’’ said Lalit Agarwal, executive director of university operations.

Highly-efficient systems mean that campus gets the desired benefit (safe, reliable, comfortable campus) from less input energy. They help the budget by reducing the fuel bills paid to our electric and gas suppliers and reduce the amount of fossil fuels needed to supply campus energy needs.

“We started thinking from a total cost of ownership mindset, rather than just focusing on the lowest first-cost,” Agarwal said. “At UNL we have done a good job of making that part of our DNA, we think energy-first to make sure that the choices we make are going to lead to those energy optimizations.”

For example, the university invested $11.9 million into its City Campus thermal energy storage tank, which went online in 2018. The 8.3 million gallon tank is designed to work like a battery by chilling and storing water during times of low demand, then utilizing the chilled water to cool campus during times of high energy demand.

This operation was designed to level out electric demand and costs. Savings were projected to be between $850,00 to $900,000 annually, and current energy savings are around $1 million annually, meaning the tank will pay for itself in around 15 years.

The university was one of the first in the Big 10 to adopt thermal storage tanks. It acquired its first, smaller tank on east campus in 2012.

Reliable energy

The 42% of campus that’s dedicated to science and research is dependent on Energy Services, meaning power outages could have severe consequences. To curtail any potential issues, and in pursuit of the goal of a reliable and responsive energy system, campus has backup generators to keep necessary projects and buildings up and running.

The university receives its energy from local sources. Lincoln Electric System provides electricity, while Black Hills Energy provides natural gas. Other sources — such as hydropower from government-owned dams in the Rocky Mountains that was allocated to the university long ago — also fuel campus energy needs.

Most buildings are served from centralized utility plants rather than individual systems in buildings. This saves time, labor and money.

The university also has the option to pre-purchase energy resources from companies to reduce costs and has backup systems such as the aforementioned generators and #2 fuel oil backup for central plant boilers.

“We have had no total utility outages,” said Conger. “Even during winter storm Uri, we only experienced a one-hour blackout in a few buildings around the edge of campus.”

During Winter Storm Uri in 2021, widespread power outages, rolling blackouts and increased electricity prices plagued citizens and college campuses nationwide.

Amidst the crisis, the University of Nebraska–Lincoln’s strategic planning and flexibility succeeded. The university only experienced the partial blackout, and the utility plants were able to switch from limited and expensive natural gas to the #2 fuel oil for a week. Switching to backup fuel saved approximately $4 million during the storm.

Automation

According to Gordian, the university has the most technically-advanced campus buildings in the Big Ten, in terms of the number and sophistication of automated controls. The control programs are cutting edge in terms of applying best-practice algorithms and designing new algorithms.

The university operates buildings, large HVAC equipment and individual rooms through its building automation system. The controls and software are designed and manufactured on campus. No other university does this. Since the university makes its own controls, it’s able to install smart thermostats in almost every room across campus. This allows individual room occupants to set temperatures to whatever suits them, and control programs automatically adjust temperatures of vacant rooms to conserve energy. This is more efficient and comfortable than other systems where three to five rooms or even entire buildings are set to the same temperature.

Advanced sensors also allow for efficient responses to energy needs and proactive maintenance. For example, staff members are able to replace filters when they’re actually dirty rather than on a preset timeline, such as every six months, reducing landfill waste.

Dedicated staff

Facilities Maintenance and Operations staff members are vital to the continued health and welfare of UNL’s teaching, programs, research and community members. They are seen nationally as innovators and have won several awards for their efforts including ACEC Engineering Excellence Awards in 2015 for the CRES system and 2019 for the City Campus Thermal Energy Storage plant. While automation has reduced the need for around-the-clock staffing in some areas, this innovation was the result of hours of research, hard work and genuine passion from FMO employees. Now, staff members’ concerted efforts focus on overseeing, maintaining and improving energy systems.

“Having separate groups managing energy use in building operations and the utility plants allows us to focus our expertise and maximize these individual systems,” said Aaron Evans, engineering supervisor for utility services. “It’s essential that we work together to get a total view of the needs of the campus community. The close working relationships we’ve developed have benefited not just our day-to-day operations, but helped us collaborate on long-term strategies that will will propel us toward reaching goals like those set out in the Sustainability Master Plan.”

For building operations, four to six engineers or highly-experienced operators oversee and improve systems day-to-day. They are supported by 15 system designers, programmers and field technicians.

The utility plant has 46 full-time personnel who actively manage equipment to serve campus. The team includes pipefitters, mechanics, engineers and safety coordinators.

Staff members also recognize the value of collaboration. They consult with controls operators, designers, programmers and planners at other universities to share experiences, successes and failures. This allows them to keep pushing forward to provide the most reliable, efficient systems possible.

Looking forward

While Energy Services is always looking towards the future in terms of innovation, efficiency, reliability and cost savings, it’s also focused on a large goal outlined in the university’s sustainability plan, which is for all buildings to reach net-zero energy by 2050.

By improving its energy efficiency by 40% since 2004, the university has already started to reduce its energy consumption and in turn, its carbon footprint. Energy Services continues to further improve efficiency campuswide, and through small changes such as replacing light bulbs with LED lights and reducing energy leakage around windows and doors also contribute to reducing energy consumption.

By utilizing the allocated hydropower, Lincoln Electric System’s renewable energy and the Thermal Energy Storage tanks, 74% of the university’s electricity is now sourced from renewable resources. However, due to natural gas use, fossil fuels still make up 66% of the university’s total energy usage.

“To reach the net-zero goal, we need a wholesale change in the way we do things,” Conger said. “So as we start to approach these goals, we’re looking for creative ways that we can do that for the least cost possible. We’re asking ourselves ‘what are the new technologies’ like geothermal and other renewable sources, that we may be able to leverage to replace natural gas usage.”