In the classroom and the lab, students learned the scientific processes behind popular food fermentation techniques as part of the University of Nebraska–Lincoln’s three-week spring pre-session course “Moldy Meals: Filamentous Fungal Food Fermentations.”

“The overarching aim was really to learn about the foods that are made with mold fungi and learn the most important mold fungi involved in food fermentation,” said Heather Hallen-Adams, associate professor of practice in food science and technology. “I wanted students to have sufficient background so that when they left the course, they’d be able to follow it further.”

The Moldy Meals course was first offered virtually in winter 2020. Its full potential sprouted through the in-person format available in the spring pre-session.

“A big part of what I always wanted to do with this course was to have the experiential in-person portion — both the more rigorous scientific aspect of looking at organisms under the microscope and making some fermented foods and tasting the foods,” Hallen-Adams said. “We can teach these fermentations more easily in person at the Food Innovation Center because we have all the food processing equipment and large-scale incubators.”

The course, which ran Jan. 2-20, consisted of three major components: lectures, microbiology labs, and food-grade labs, where students tasted and sometimes prepared fermented foods.

Throughout the course, students learned about and tasted a variety of fermented foods, including nine soy sauces, fermented sausage and various cheeses.

Learning about popular food fermentations and how to do them at home is a major focus of the course, and Hallen-Adams provided students with a hands-on learning experience that will allow them to take what they learn and apply it to their lives — whether personally, professionally or both.

“If I were a student taking a food fermentation class, I’d like to know what the foods tasted like,” she said. “And to the extent possible, I’d want to know how to do this myself at home. I want to give people the tools to carry these lessons further into their futures.”

While providing students with valuable knowledge, Hallen-Adams encouraged students to try new things.

“I like to have some things that are a little bit different,” she said. “For example, they’ve probably never sat down and tried nine kinds of soy sauce, and it’s something not everyone would normally have the chance to do. They’re being exposed to foods that might be a little outside of their comfort zones. I’m never going to make anyone eat anything, but they have the opportunity, and most people have been trying them. They’re not excited by everything, but some of them are being surprised by ‘oh, I do like this’ or some of them will say ‘I’ve tried that once and that’s enough for me.’”

The taste tests were popular with students.

“My favorite part of the class has been tasting the food,” said Zhuo Chen, a senior food science major. “Some of the foods are not great, but it’s fun to taste them.”

Other students had their preferences. A favorite among the class was a wild mushroom soup.

“At one point the students ate fish fillets and chicken cutlets that had been marinated overnight in a fungal fermentation called Shio Koji, which the students prepared a week in advance, incubated and watched that fermentation develop,” Hallen-Adams said.

Sioi Koji is a fermentation that’s been used for millennia to make soy sauce, miso and other traditional fermented Asian foods. It started to gain popularity around 2018, and since, people have begun to use it for other things like cooking meat and vegetables, and incorporating it into baked goods.

“There’s just a huge amount of interest at the restaurant level and the foodie level in starting to look at these products,” Hallen-Adams said. “A book on Koji alchemy was part of what inspired me to make this a course topic.”

Interest in fermented foods is on the rise. For example, Kombucha has been around for some time, but wasn’t commercialized until the past decade. A lot of the interest in fermented foods has stemmed from growing awareness about overall health and gut microbiome health. There’s a big interest in probiotics, which can be naturally obtained through a diet containing certain fermented forms of foods like sauerkraut.

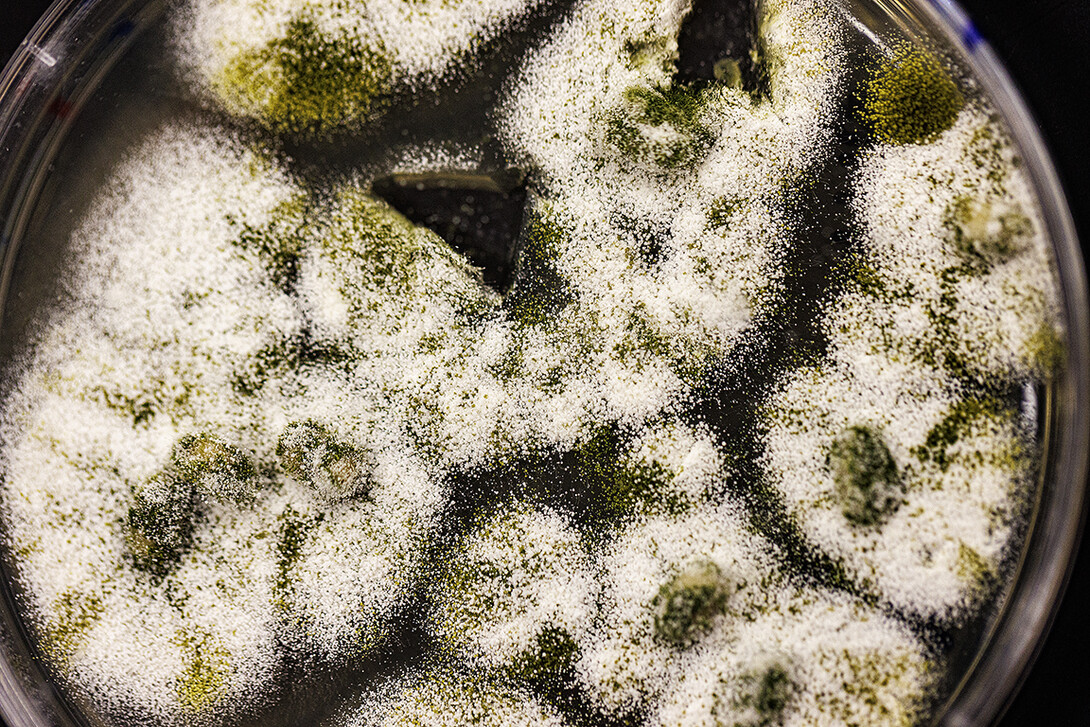

“Tempe is another fermented food that’s been around for some time,” Hallen-Adams said. “But it really wasn’t mainstream until the past five or 10 years. Tempe traditionally is a soybean product, made by very short fermentation with a mold called Rhizopus. It’s pretty bland on its own, so we made it into Reuben sandwiches in class.

“I think the combination of the possible health benefits and the chance to be creative and make something different with these fermented foods, really excites people. This is kind of a moment when all that’s coming together, and we’re at the point where we’re starting to know a lot more about gut health and about the role of microbes. Right here on campus we have the Food for Health Center which ties into this as well.”

The interest in fermentations has risen so much that a fermentations minor was recently approved.

In addition to showing students the world of food fermentations, the course fulfilled university or college requirements for many students.

“I think some of the students like having the three-week option because even though it’s a fair amount of work in three weeks, you’re generally only taking that one class and then going into the rest of spring semester only having to take 12 credits and the rest of the semester can be a little more relaxed,” Hallen-Adams said.

Her students agreed.

“We wanted to make use of our holiday break to fulfill some of our credit requirements, while learning about fermented food,” Chen said. “Heather Hallen-Adams is a really good teacher and she’s very thoughtful.”

“Her teaching methods are very chill,” added Baoyue Zhang, who is also a senior food science major. “She has great banter and makes it fun to follow her material and learn something along the way.”

Looking back on the past three weeks, Hallen-Adams appreciated the course format that rose from the three-week time frame.

“We have the lecture and lab component every day that the course meets and it meets four days a week, for three weeks,” she said. “In a full semester, it would be probably meeting once a week for lecture and once a week for lab. With the three-week session, the time frame for some of these fermentations works well to look at something every day or start fermentation and two days later, take it down and deal with it. The time frame would be a little more difficult to work into a full semester.”