A University of Nebraska research team is working on a critical issue in agriculture and automated systems: cybersecurity for agricultural machinery and technology.

Santosh Pitla, associate professor of advanced machinery systems at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, brought together team members from the Nebraska U and University of Nebraska at Omaha campuses in fall 2020 through a project looking at the security and hackability of autonomous farm vehicles that was supported through the University of Nebraska Collaborative Initiative seed funding.

In addition to Pitla, the group included Mark Freyhof, master’s student in agricultural engineering at Nebraska; George Grispos, assistant professor of cybersecurity at UNO; and Cody Stolle, research assistant professor at Nebraska.

Since this is a relatively new area of research in agricultural systems, collaboration has been key. Pitla has been working with autonomous tractors and agricultural robotics since 2010. While most of his focus has been on making different autonomy levels feasible, he started working with Grispos once engineers started integrating the Internet of Things into the machinery.

“It’s been a really fruitful collaboration,” Pitla said. “Agriculture researchers and cybersecurity experts are both really important to conduct research in the cybersecurity area (of agricultural technology). This allows us to really be proactive and find solutions or mitigation techniques.”

This topic is becoming increasingly relevant as farmers try to produce more food with fewer resources, Grispos said in a Fast Company article he co-authored.

“The advent of precision farming comes at a time of significant upheaval in the global supply chain as the number of foreign and domestic hackers with the ability to exploit this technology continues to grow,” he wrote in the article.

In addition, cyberattacks in the ag sector have already occurred. For example, in 2021, a grain storage cooperative in Iowa was targeted by a Russian-speaking group called BlackMatter, Reuters reported.

Grispos said the integration of automated technologies in farm equipment has the potential to increase vulnerability to cyberattacks, even on smaller farm operations.

“While previous attacks have targeted larger companies and cooperatives and aimed to extort the victims for money, individual farms could be at risk, too,” he said.

Freyhof conducted research on agriculture cybersecurity for his master’s project, with Pitla serving as the principal investigator and Grispos and Stolle as committee members.

Breaking ground in this project area was both “cool and challenging at the same time,” Freyhof said.

“There was little previous literature that investigated cybersecurity solutions for agricultural technology and machinery — therefore, a large part of the project involved tying many interdisciplinary topics together,” he said. “This made for a challenging but fun project.”

To approach the topic, Freyhof started by conducting a case study of cybersecurity breaches on agricultural equipment, using Flex-Ro as a test case. Flex-Ro is an agricultural robot that can be controlled remotely and operated autonomously.

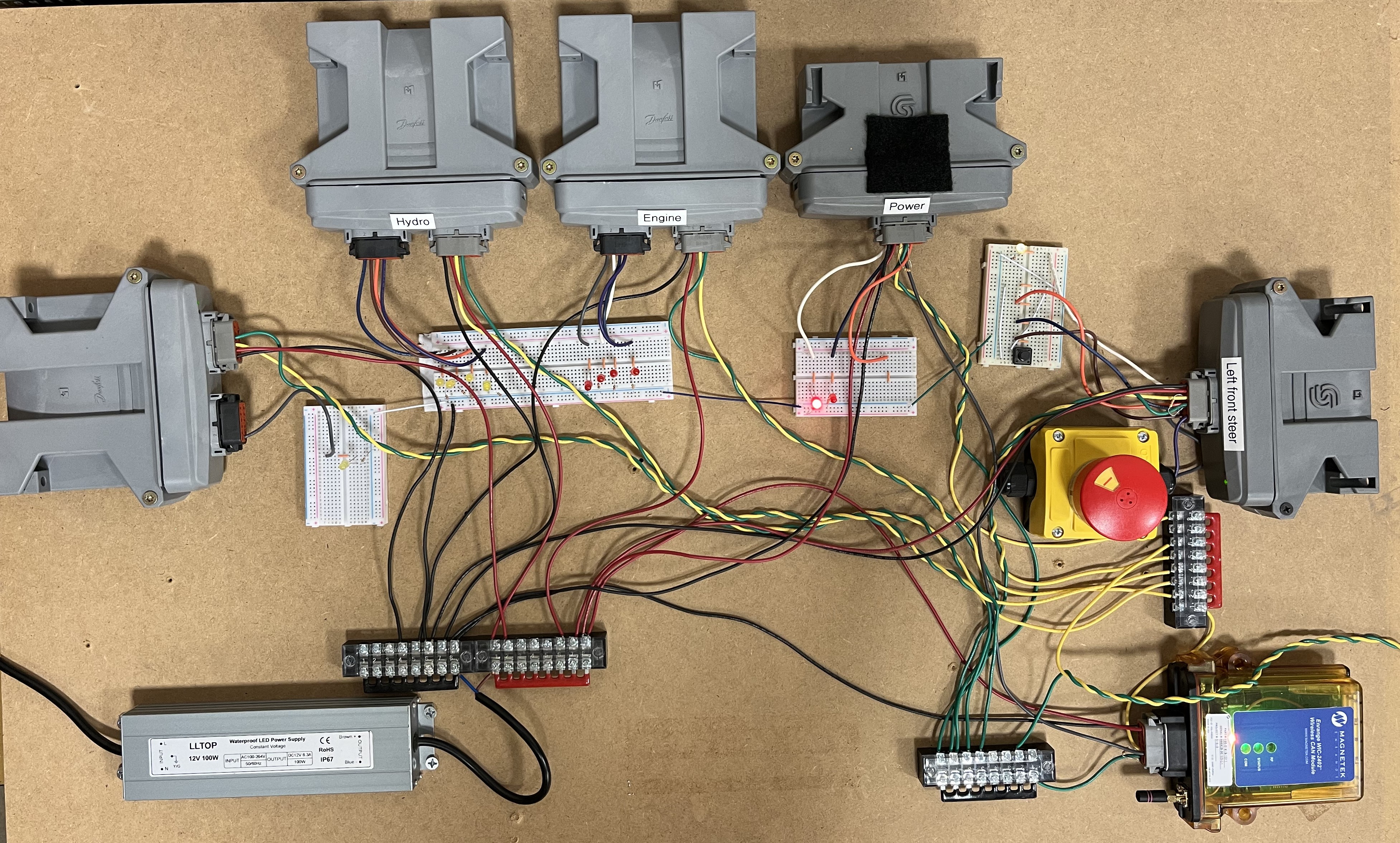

Rather than perform tests directly on Flex-Ro, Freyhof decided to build a testbed to investigate specific systems on the Flex-Ro machine to avoid performing potentially damaging tests on the machine itself.

The testbed, named Security Test Bed for Agricultural Vehicles and Environments (STAVE), was a useful tool for investigating cybersecurity vulnerabilities on Flex-Ro. It has great potential in future research into cybersecurity of agricultural machinery, Pitla said.

The group published a research paper about the ways STAVE could be used, which was selected as the best paper at the Midwest United States Association for Information Systems conference earlier this year.

“The reality is, agricultural machines and other agricultural technologies have an increasing level of integrated digital solutions as they move closer toward full autonomy,” he said. “Cybersecurity cannot be an afterthought, as the world will be dependent on these machines and technologies in the future.”

Pitla agreed that potential vulnerabilities need to be addressed to effectively advance the future of agriculture.

“You could have really smart equipment — an autonomous machine with a lot of computers, lots of sensors, artificial intelligence — but if it has a weak link with respect to cybersecurity, all that intelligence is of no use,” he said.

“Providing safe and secure agricultural machinery is important for food and national security. IANR is rightly positioned to provide strategic leadership in creating cyber-safe agricultural production systems.”

Freyhof graduated in August and will continue to work as an engineer for Precision Planting in Illinois. Pitla said the research team’s experience developing STAVE will help with plans to build security testbeds for smart and autonomous systems of the entire food supply chain.