Houston, we have remote surgery!

In a test that featured half a dozen surgeons from across the United States, a miniature robot created at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln successfully completed a surgical simulation aboard the International Space Station.

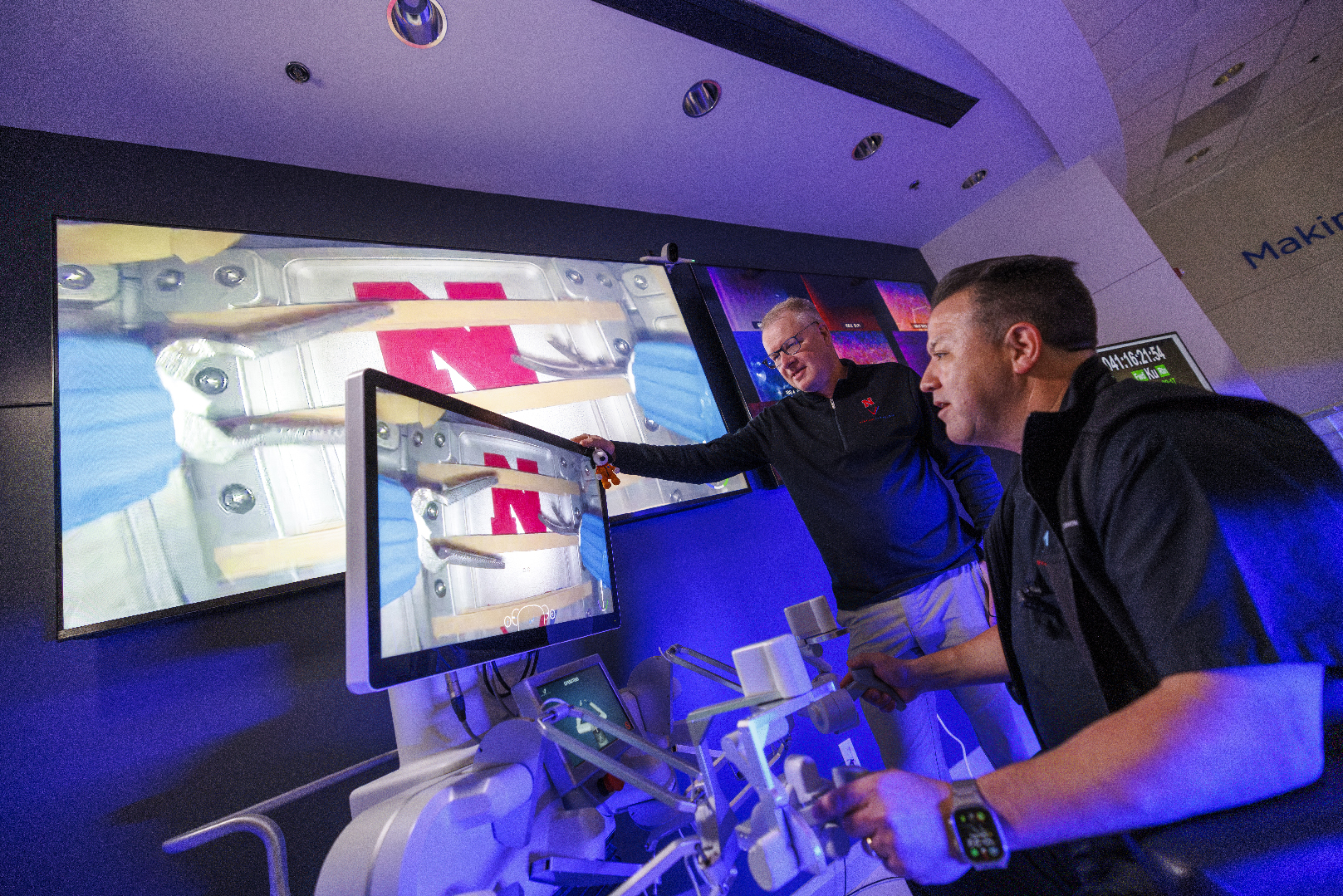

“Tell the astronauts they have six extra surgeons today,” said Yuman Fong, a liver surgeon from the City of Hope Cancer Center in Los Angeles, as he watched a surgeon from Houston guide the robot using hand and foot controls from a console at the Lincoln headquarters of Virtual Incision, a private company created to develop the MIRA robot.

“If they ever need us in the future, it would take us less than a second to get there.”

MIRA — which stands for Miniaturized In Vivo Robotic Assistant — was developed under the leadership of UNL’s Shane Farritor, Lederer Professor of Engineering and a Virtual Incision co-founder. It is the world’s only small form factor robotic-assisted surgery device. The Nebraska research team leveraged MIRA’s unique design to create spaceMIRA, an iteration that allows pre-programmed as well as long-distance remote surgery operation modes.

“SpaceMIRA’s success at a space station orbiting 250 miles above Earth indicates how useful it can be for health care facilities on the ground,” Farritor said.

Farritor and doctoral student Rachael Wagner obtained grant funding through NASA Nebraska Experimental Program to Stimulate Competitive Research (EPSCoR) to send the robot to the International Space Station. The robot blasted off Jan. 30 from Florida’s Cape Canaveral Space Force Station aboard a SpaceX rocket carrying a Northrop Grumman cargo vehicle.

It is the first surgical robot aboard the space station and one of the first times remote surgery tasks have been tested in space.

Wagner, who is pursuing a doctorate in biomedical engineering at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, served as “mission control,” communicating with NASA’s Payload Operations Center at Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, during the Feb. 10 simulated surgery. Later, she briefly took the robot’s controls, as the surgeons applauded her as the first woman to operate spaceMIRA in space.

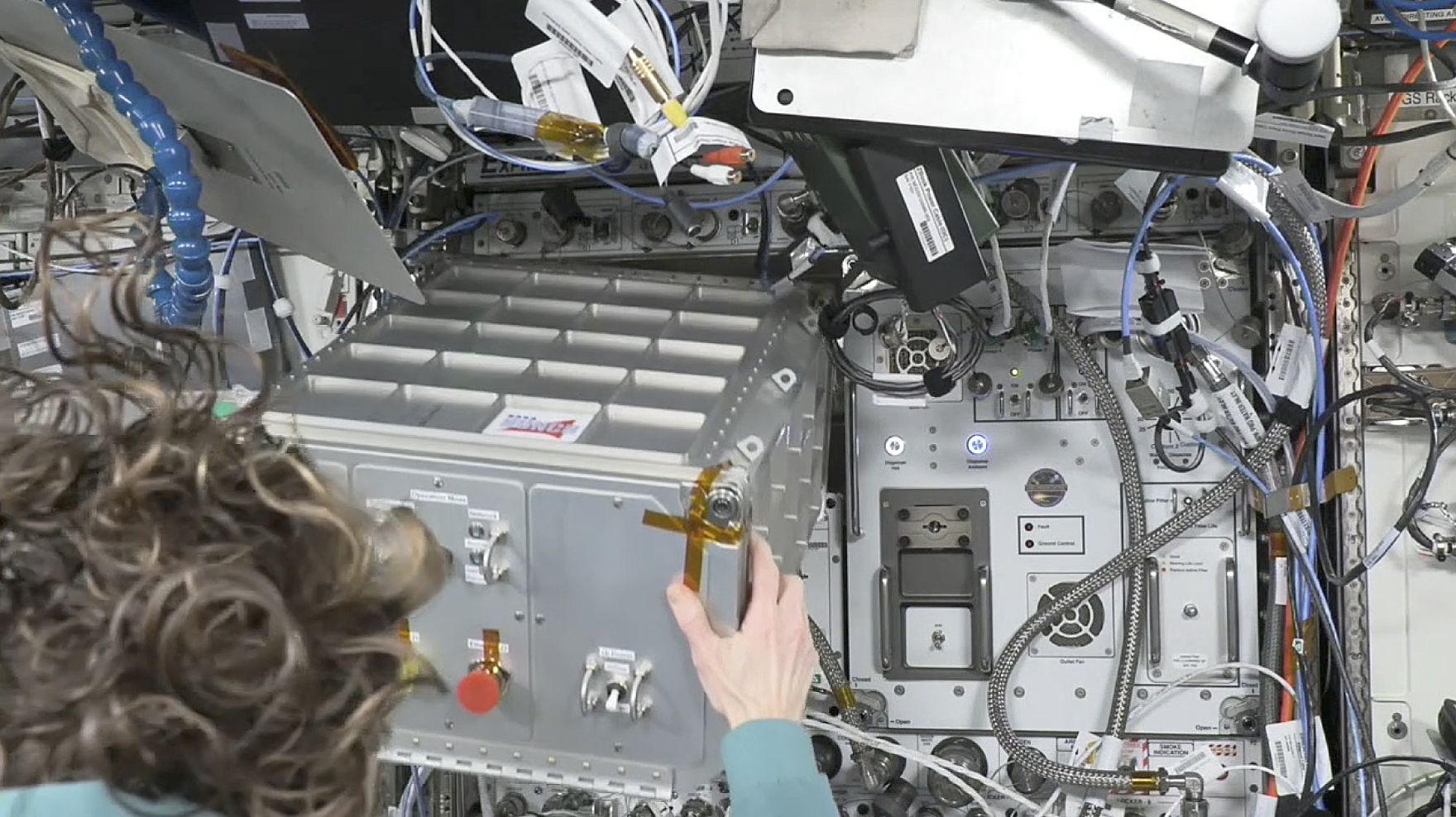

SpaceMIRA, which is about 30 inches long and weighs about 2 pounds, performed its maneuvers while inside a microwave-oven-sized experiment locker. The cylindrical device, which looks a bit like an oversized stick blender, is topped with two arms — the left fitted with a grasper, the right with scissors. An integrated, articulating camera enables the operator to see the robot as it works.

During the surgical demonstration, the signal latency ranged from two-thirds to three-fourths of a second gap for action at the control center to be executed by the robot aboard the Space Station.

To compensate for the lag, engineers experimented with different scaling factors for the Earth-based controls, so that bigger motions on Earth would result in smaller movements by the robot.

“You have to wait a little bit for the movement to happen, it’s definitely slower movements than you’re used to in the operating room,” said Michael Jobst, a Lincoln-based colorectal surgeon, as he took the first turn at the controls.

Jobst has participated in 15 previous procedures with MIRA, including using it in a 2021 clinical study to remove part of a patient’s colon during procedures at Bryan LGH Medical Center in Lincoln in 2021. Jobst’s experience showed as he adeptly maneuvered the device and its arms inside the locker.

Several of the surgeons said they were awestruck that spaceMIRA could operate in space. But it is the robot’s potential usefulness on Earth that really excites them.

“It’s a great leap for surgery,” said Ted Voloyiannis of Texas Oncology in Houston. Voloyiannis has performed more than 1,000 robotic-assisted surgeries during the past 15 years. But surgical robots commonly used today are much larger, taking up an entire room.

“This robot is more accessible,” he said. “It is easier to train on and it will be available to small communities without specialized surgeons.”

While a large monitor on the right of the control center showed multiple views of Earth from the Space Station, screens on the left side of the room provided the robot’s operator a view of the robot’s hands and the work station inside its box. A total of 10 rubber bands were tethered on metal panels to the left, right and center before the robot. In a simulation of motions, tension and texture of tissue in surgery, the surgeons’ task was to maneuver the robot into position and use its “hands” to grasp the band, pull it taut and cut it.

After each band was cut in the front and in the back, for a total of 20 possible cuts, its still-attached ends floated nearly motionless in microgravity. In a brief orientation session led by Virtual Incision engineer Lou Cubrich, the surgeons were warned not to cut the bands into multiple pieces and not to risk breaking the robot by bumping it into the sides and back of the experiment locker. Any loose debris could prove disastrous to the Space Station.

“This is just amazing,” said Dmitry Oleynikov, Virtual Incision’s chief surgeon, as he took a turn maneuvering spaceMIRA. Oleynikov is a co-founder of Virtual Incision and worked with Farritor to develop the robot.

“It looks like you’ve done that before,” an observer commented.

“I’ve not done this in space!” Oleynikov replied.

Share

News Release Contact(s)

Related Links

Tags

High Resolution Photos

HIGH RESOLUTION PHOTOS

HIGH RESOLUTION PHOTOS

HIGH RESOLUTION PHOTOS