A colon-dwelling bacterium may trigger inflammatory bowel diseases by raising the immune system’s alarm against its peaceful bacterial community, reports a recent study led by the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

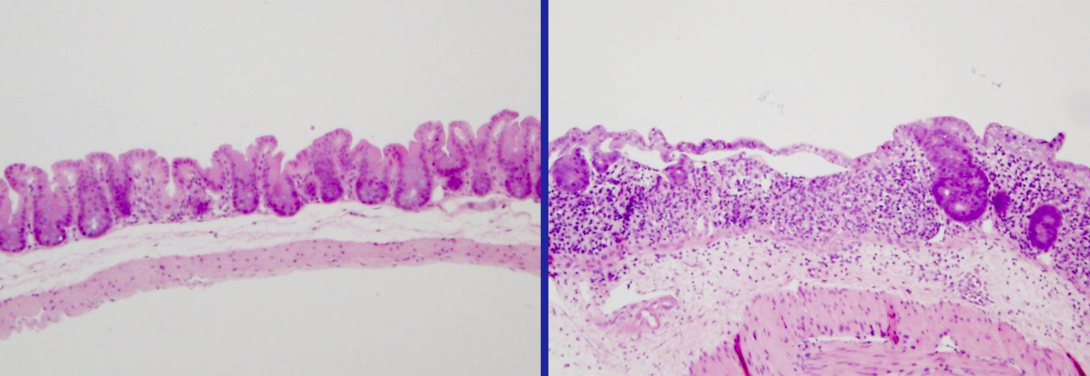

In the absence of its bacterial neighbors, the offending Helicobacter bilis bacterium caused only mild gut inflammation in mice, the research team reported. But adding a community of just eight other bacterial species into the mix — a typical human gut contains several hundred — was enough to stir up a more severe inflammatory response.

Surprisingly, Nebraska’s Amanda Ramer-Tait and her colleagues also found that the H. bilis bacterium managed to avoid falling victim to the immune response it instigated.

“What hasn’t been reported in the (research) literature is that there are organisms, like the Helicobacter in this example, that contribute to the disease process but are not overt targets of that process,” said Ramer-Tait, Harold and Ester Edgerton Assistant Professor of Food Science and Technology.

The researchers studied H. bilis because it can act as a pathobiont — an organism that normally lives harmoniously with its host but can drive disease when that equilibrium gets thrown off balance. In humans, a thin intestinal lining helps maintain a truce by separating 100 trillion gut bacteria from roughly 70 percent of the body’s immune tissue.

“Under normal conditions, the immune system tolerates gut bacteria,” Ramer-Tait said. “But sometimes there are breaks in the intestinal barrier because of either a genetic susceptibility or an environmental trigger, which is similar to creating a hole in a fence. That breach then increases the likelihood that the immune system will launch an attack.”

When damage befell the intestinal lining, the immune system reacted not to the H. bilis but instead to three of the study’s benign bacterial species. This finding suggests that many different bacteria native to the gut might draw the ire of the immune system, Ramer-Tait said, and ultimately contribute to inflammation.

Inflammatory bowel diseases such as ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, which can cause symptoms ranging from abdominal pain to diarrhea, afflict more than 1.5 million people in the United States alone. Though prior research has established strong links among dysfunctional immune responses, gut microbes and bowel inflammation, the precise cause of disease remains unclear.

“What this study tells us, overall, is that there’s probably not one specific microorganism that’s responsible for disease in IBD patients,” said Ramer-Tait, a member of the Nebraska Food for Health Center. “That idea has been a big focus in the field for years, because people have been looking for the microbe that contributes to disease. However, it may be that certain features shared by multiple microbes are perpetuating disease instead. Perhaps we should be looking for those characteristics as opposed to trying to identify a specific causative agent.

“What makes a good microbe go bad? That’s the question I think we should be asking.”

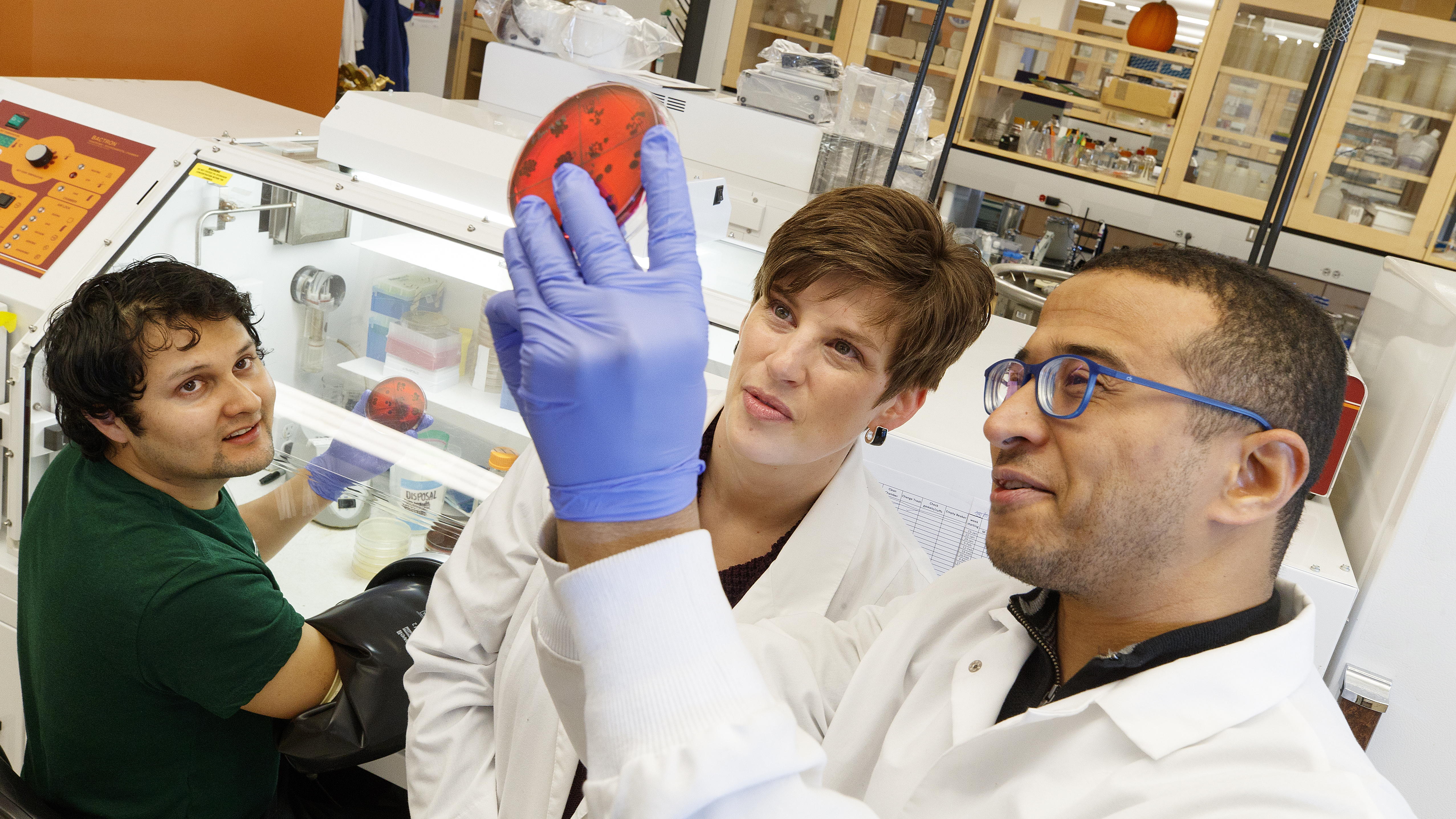

The researchers detailed their findings in the journal Scientific Reports. Ramer-Tait authored the study with João Carlos Gomes-Neto, a Nebraska doctoral graduate now at the University of Utah; Jens Walter of the University of Alberta; Jennifer Clarke, professor of food science and technology and of statistics; Andrew Benson, professor of food science and technology and director of the Nebraska Food for Health Center; Robert Schmaltz, research manager in food science and technology; Laure Bindels, a former postdoctoral researcher at Nebraska; Hatem Kittana and Rafael Segura Munoz, graduate students in food science and technology; Sara Mantz, a 2017 Nebraska graduate; and Jesse Hostetter of Iowa State University.

The team received support from the National Institute of Health’s Institute of General Medical Sciences, under grant number 1P20GM104320, and the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America.