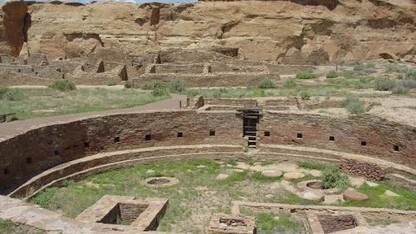

More than 1,200 years ago, an ancient society settled in the San Juan Basin of what eventually became New Mexico. They built great houses and other expansive structures out of mortar and stone, becoming home to thousands of indigenous Pueblo people.

Some of the ruins of this ancient architecture are preserved by Chaco Culture National Park in northwest New Mexico and provide a glimpse into the 1,000-year-old culture. But the anthropological resources of Chaco Canyon extend well beyond the park’s gates, and are being overtaken by concrete, oil pads and derricks – the effects of an oil and natural gas boom.

The infrastructure is encroaching on, and in many cases destroying, these ancient relics, largely because no one knows the exact locations of primitive landscapes and roads.

With the help of NASA, University of Nebraska-Lincoln anthropologist Carrie Heitman and graduate student Sean Field are building a network of digital maps, or a Geographic Information System, that will plot all known Chaco cultural resources in the Southwest region, specifically where the corners of Utah, Arizona, New Mexico and Colorado meet.

This digital geographical record of prehistoric buildings, roads and landmarks is helping to inform the federal Bureau of Land Management on decisions regarding land leases for oil and gas development – and also protect Chaco sites.

“The impact we’ve seen from oil and gas infrastructure is very real and it’s already well under way,” Heitman said. “In working with the agency, and looking at the maps they had, it became clear that they had imperfect data.”

Heitman has focused much of her anthropological expertise on further understanding the Chaco culture, including direction of the Chaco Research Archive. Several years ago, under Heitman’s leadership at Nebraska, and with a collaboration with Milda Vaitkus at the university’s Center for Advanced Land Management Information Technologies, a comprehensive database of known Chacoan great houses throughout the San Juan Basin was started. Field advanced that research, using previously published maps to add roads as a new data layer within the GIS.

The National Park Service, which funded Heitman’s work on the great house database, forwarded the Chaco Canyon project to the NASA Develop program. The NASA Develop program uses NASA’s previous Earth observations – everything from thermal imaging of land to satellite photographs – to address environment and policy concerns.

“We pointed out to the NASA team that our prior work with the great house and roads data would provide the necessary foundation for their study,” Heitman said. “By starting there, and adding in the NASA data sources, we could go from the known to the unknown and they could start looking for undiscovered roads.”

The NASA Develop team spent six weeks on the project, and used data from thermal soil imaging, which measures the heat index of the ground; hyper-spectral data, which uses the reflection of light to create images; and Google Earth to examine about 4,600 square miles. It was determined that of the 123 known Chacoan great houses, 44 are at high risk for disturbance by encroaching oil and gas harvesting and storage facilities and concrete roads. About a dozen possible road and landscape sites previously unknown to scholars were also recorded.

“They saw anomalies that hadn’t previously been documented,” Heitman said. “We would have to go out and actually do some further testing to determine if those are true archaeological deposits, but it is really promising.”

With the possibility of finding more cultural resources in the area and the emergence of newer technologies, Heitman said the NASA Develop project is interested in furthering Chaco Canyon exploration in 2017. Newer NASA data that is higher in resolution also will be available soon, and that adds more possibilities for the Develop team.

“We have a really clear path forward, and our hope is that we will continue this project during the spring 2017 NASA Develop term,” Heitman said.

Working with the NASA Develop project is just one piece of the puzzle to help preserve as much of the ruins as possible, which are important to understanding our collective pasts, she said.

“This is all part of our shared cultural patrimony, of all the people who have lived in North America,” Heitman said. “It’s important to know about the past, about what came before.

“It’s complicated to find a balance between developing for the future and protecting our collective past, but we owe it to everybody to have the most complete information to make the best decisions we can,” she said.