For the past decade, James Le Sueur has traveled the globe, interviewing Muslim artists, writers and thespians who have lived in hiding from radical Islamists who have placed fatwas, or death orders, on their heads.

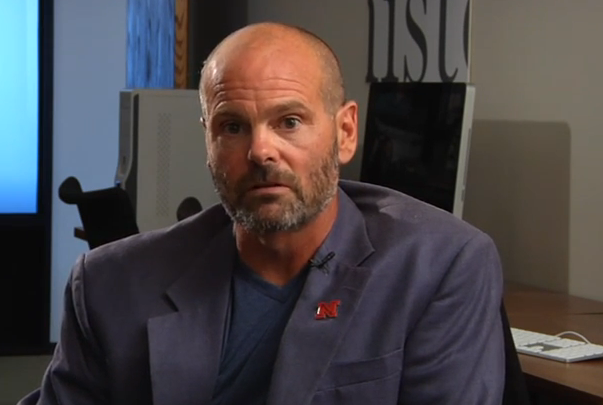

Le Sueur, University of Nebraska-Lincoln professor of history, used selected interviews to show the power of intellectual Muslims against radical Islam during a standing-room-only presentation in Andrews Hall on Dec. 8.

During the talk, titled “Clashing with the ‘Clash of Civilizations’ Thesis: A Documentarian’s View of the Debate over ‘Radical Islam’ and the War on Terror,” Le Sueur explained how intellectuals from Muslim-majority nations fled their home countries and found themselves using the pen as weapon against the ideologies of terrorist groups such as al-Qaeda.

He also discussed how the exile of millions of Muslims during civil wars – such as the Algerian civil war in the 1990s, during which many exiles fled to France – has created a vacuum of rational, democratic leadership in many countries and has allowed old and new terrorist groups to flourish.

“Two million people went into exile during (the Algerian civil war), which means the entire civil society of a country was killed, was snuffed in its crib,” Le Sueur said. “When you have a civil society decimated, it’s pretty hard to have tolerance, democratic platforms, et cetera, come online.”

But these expatriates did not go quietly. Many stayed active in critiquing radical Islam. One interviewee said terrorist acts had actually pushed Muslim writers and artists to be more vocal in the fight against militant regimes.

“There was a dominance of self-censorship (prior to the civil war),” Le Sueur said. “You never really said what you thought because if you did, you were going to jail and would likely be tortured and killed by the regime.

“But because the terrorism activated such fear and such panic, it also liberated writing. The choice was clear: You were going to die whether or not you critique what is happening, so it’s better to say what you actually think. That was the end of self-censorship.”

Most importantly, Le Sueur wanted to highlight how Muslims are often the first targets of radical Islamists, which counters the perception in popular news media. Le Sueur singled out the rhetoric from presidential candidate Donald Trump and his supporters as particularly dismissive of millions and millions of Muslims who are trying to “recapture Islam from these radicals.”

“We need to be aware that Muslims are at the front line of this more than any other people,” Le Sueur said.

“There are all these Muslim writers and intellectuals out there and most Muslims are not radical Islamists or this Trumpian view of the world,” he said. “They’re rational, they’re intellectual and they’re pretty outspoken. And it’s that group of people that we have to help in every way. We need to support civil society and public debate and not allow people to demonize others because of perceived threats.”

Le Sueur said the anti-Muslim rhetoric that has bled into U.S. political discourse since the Nov. 13 attacks in Paris and last week’s mass murders by alleged ISIS sympathizers in San Bernardino, California, is hurting a vast majority of Muslims, who disagree with radical Islamists. It also is hurting the United States in its fight against radical groups.

“When the Paris attacks happened I decided that I needed to talk about this publicly because it’s not just something that I’ve started to do,” he told the audience. The hundreds of hours of footage from Le Sueur’s interviews will eventually be a documentary film, “Exile and the Fatwa.”

“I’ve been working on this for 10 years because I care about how Islam is represented in the United States and around the world.”