In Brazil, the suicide rate for young people has increased more than 50% since 2000. Experts suspect systemic problems like public health policies, cultural attitudes toward mental health, social and political change, and increased internet use all play a role in the epidemic.

University of Nebraska-Lincoln researcher Cody Hollist, an expert in Brazilian family resilience, believes other, more personal factors are also at play, such as trauma, family dynamics and substance abuse. He will use a Fulbright U.S. Scholar Award to dig deeper into how these factors are driving the uptick, and how the COVID-19 pandemic may further exacerbate the trend. He’ll also establish a baseline rate of non-suicidal self-injury in Brazil, which is currently unknown.

Using the data they collect through interviews and surveys, Hollist and Brazilian collaborator Ana Lucia Horta will develop interventions aimed at decreasing Brazil’s suicide rate and reducing self-harm.

“We want to create family-based interventions founded on early indicators of risk, designed for schools and medical facilities,” said Hollist, associate professor of child, youth and family studies. “We want to make sure the people who are intervening are paying attention to behaviors associated with self-harm and suicide.”

His Fulbright tenure is scheduled for January to May 2021 at the Federal University of São Paulo, known as UNIFESP, in São Paulo, Brazil.

To this point, nobody has quantified the degree to which self-harm, commonly known as cutting, is occurring among Brazilian youth and young adults. Doing so is crucial for several reasons, Hollist said. The behavior in and of itself is traumatizing to a family, leading to cyclical disruptions. Self-harm is also closely tied to suicidal thoughts and suicide, making it a risk factor for what is the second-leading cause of death worldwide among 15- to 25-year-olds.

He’ll also delve further into how trauma drives self-harm and suicide, which is an extension of his past work in Brazil exploring family well-being in high-risk environments. Current events have added a new twist to that line of research. The COVID-19 pandemic is hitting Brazil hard: As of April 21, the country had more than 40,000 confirmed cases – the most in Latin America – and more than 2,500 deaths.

Conducting research on trauma amid a global crisis will be challenging, but is more critical than ever because of the pandemic, Hollist said.

“The pandemic will impact the study, because now everyone has been through a traumatic, or at least bizarre, event,” Hollist said. “We’ll have to shift the project to include looking at how a specific trauma – the pandemic – affects suicidal thoughts and behaviors. This understanding will be critical in the aftermath of this pandemic.”

Hollist will also teach two courses at UNIFESP, aiming to bring students a new perspective on family therapy, which follows different principles in Brazil than it does in the U.S. In the latter, it’s typical for researchers to develop and test interventions to improve real-world outcomes. In Brazil, the focus is largely on basic science without testing in the clinic. Hollist said he hopes to boost students’ understanding of how, as future clinicians, they can use and contribute to research to help families.

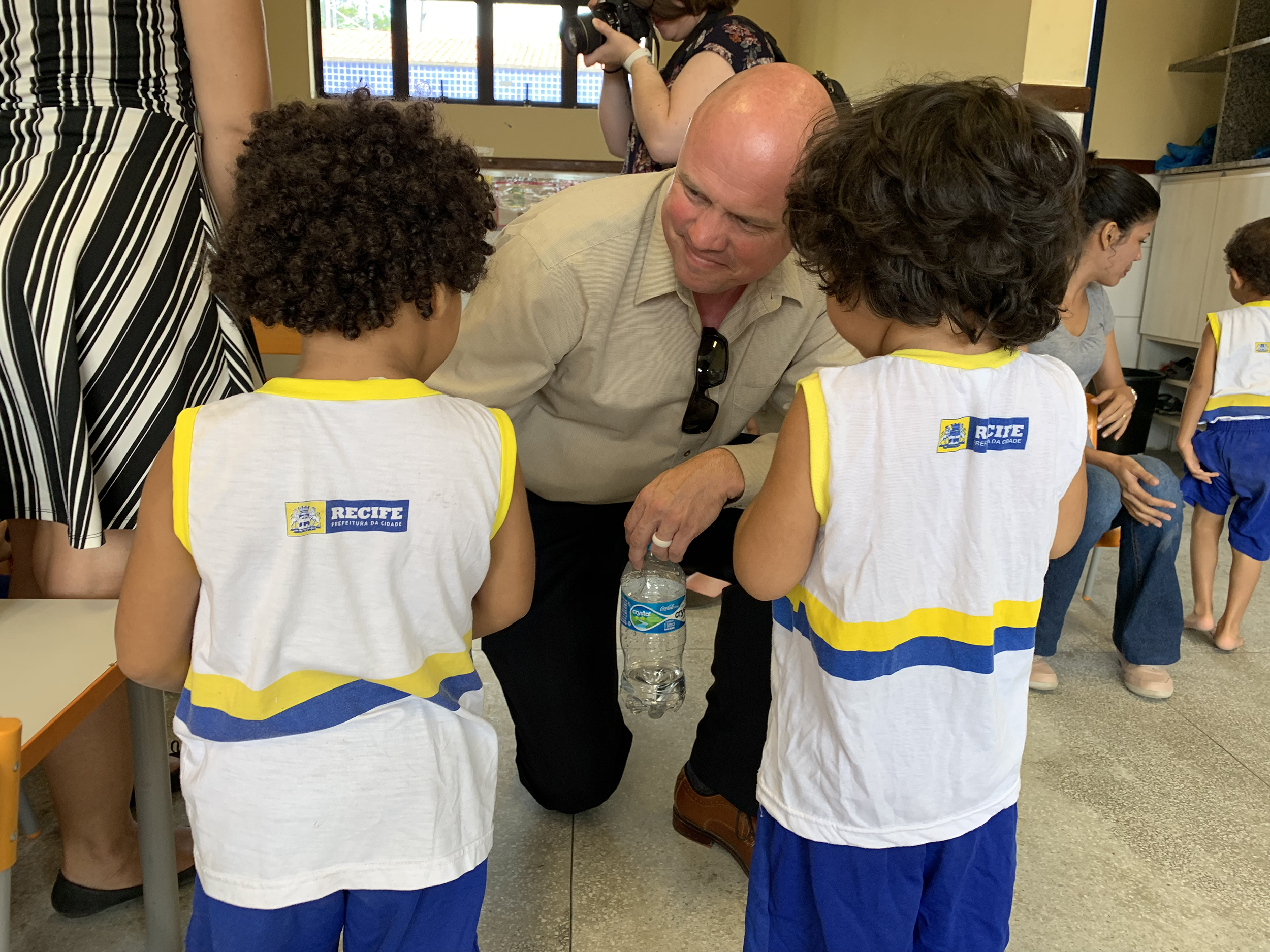

Hollist has deep ties to Brazil and its people. He initially spent two years in the country when he was 19 years old, becoming fluent in Portuguese as he worked as a missionary. He established his first research partnership in southern Brazil in 2003, which produced a steady stream of publications and mental health interventions until 2016, when Hollist’s in-country collaborator retired. He then helped Nebraska launch a formal partnership with the Maria Cecília Souto Vidigal Foundation in 2016, which laid the groundwork for this Fulbright project.

On a more personal level, Hollist adopted a son from Brazil when he was 5 years old. Now 18, his son, along with the rest of the family, hopes to travel to São Paulo for Hollist’s Fulbright tenure, which would mark his son’s first time in Brazil since his adoption.

Bigger picture, Hollist hopes his four-month period of study in Brazil will enable him to make an impact that’s difficult to achieve from afar. Although suicide and self-harm are pervasive around the world, the contributing factors differ in each location according to the unique social, political and cultural contexts at play. Interventions cannot be one-size-fits-all – to be effective, they must be tailored to the norms of the people involved.

“International collaboration is so complicated because it’s necessary to demonstrate to colleagues in other countries our commitment to them and helping their well-being,” Hollist said. “I’m really excited about being in Brazil for a long enough time to demonstrate a commitment to them and to developing something that doesn’t just get good publicity, but that makes a difference for people.”