Nebraskans know wind. The Plains region is known for the fierce spirit of its winds, from ceaseless high-plains howlers to rampaging tornadoes to dangerous snow-blown whiteouts.

Now, a new wind climatology tool available online from the High Plains Regional Climate Center provides detailed wind data for any location in Nebraska, as well as the center’s six-state region. The center, affiliated with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, is operated by the University of Nebraska–Lincoln’s School of Natural Resources.

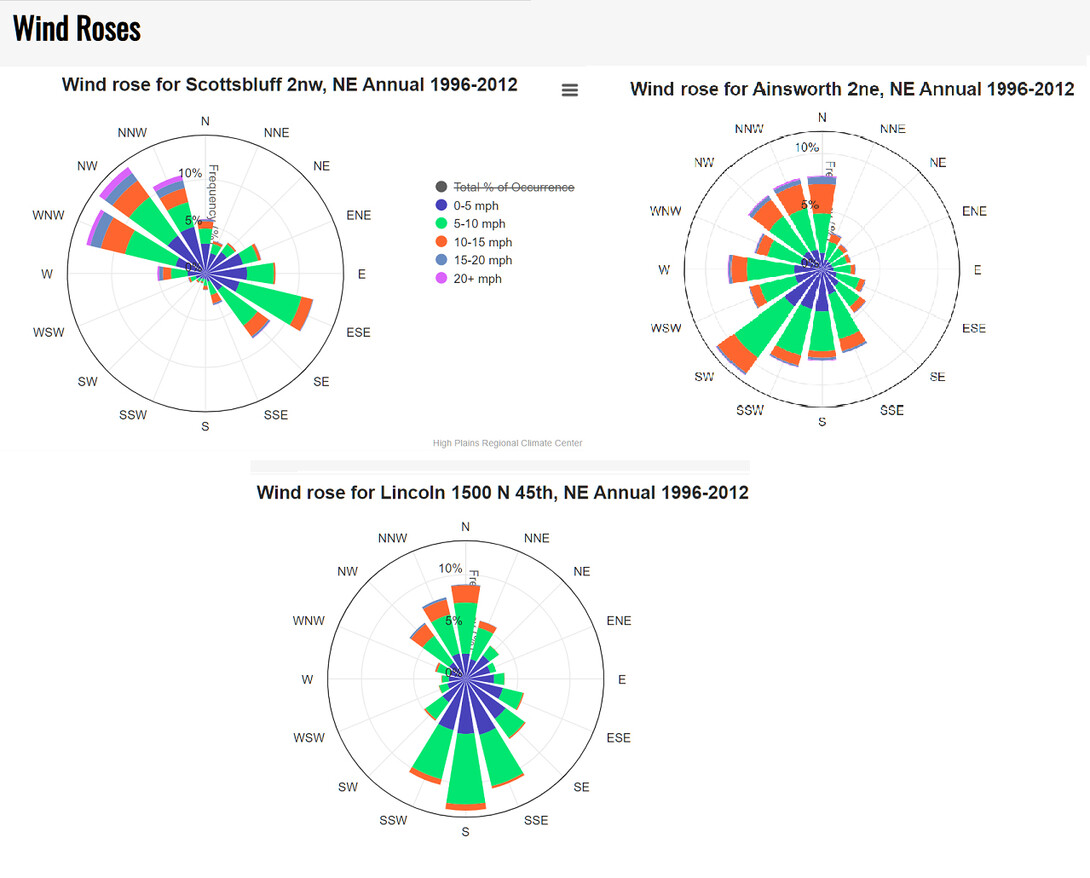

The web application is the latest addition to the center’s wide-ranging set of online climate-data services and enables users to access monthly wind data from 1985 through 2022. The resulting information — monthly wind direction and wind gust hours depicted graphically, plus the location’s number of low- or high-wind months for each year — has practical value for firefighting, agriculture and the energy sector.

The wind data can help firefighters during fire season when they want to know which direction the wind most commonly blows over certain summer months, said Jamie Lahowetz, who manages the center’s Automated Weather Data Network, which collects and processes climate data across the six-state region. Using the wind-data tool, firefighters “can prepare themselves and keep a watchful eye on which direction they should be looking for when there’s a fire.”

Similarly, wind data is important for managing pesticide application and installing wind turbines at the most wind-productive sites.

Long-term analysis shows that a location’s wind patterns do not necessarily remain constant over time — hence the importance of the center’s new online tool.

“It’s a large swath of data over many decades, which lets us see how that wind actually changes over time,” Lahowetz said, “and then you can better understand what to expect.”

Lincoln provides an example, he said, as its number of low-wind months almost doubled during 2015-20 compared with the 1990s and early 2000s. “That tells us that the wind slowed down over that period,” he said, “and that we didn’t have as many of these really screaming wind days.”

Lahowetz’s fascination with weather began during his childhood in Grand Island, when he developed a keen interest in the whys and hows of lightning. During his undergraduate and graduate studies in meteorology at Nebraska, he had extensive experience studying extreme wind conditions. In collaboration with Adam Houston, professor in the Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, Lahowetz worked in the field with drones and related technologies to anticipate and monitor thunderstorms and tornadic activity.

Through that work, he gained expertise in developing weather-focused software. “That’s where I got into developing systems for climate use,” he said, “and that kind of led me to the (High Plains) center,” whose work focuses on six states: Nebraska, Wyoming, Colorado, North Dakota, South Dakota and Kansas.

“It’s interesting to see how the wind evolves as it goes across the state,” Lahowetz said. “Nebraska is a place where you have wide-open areas, and then you have wind-swept Sandhills and also the metro areas toward the Missouri River.”

The climate center’s wind-data tools explain that “not everywhere in the state has the same speed of wind and the same direction of wind. This even changes over seasons. In Nebraska, we tend to have the highest winds in wintertime.”

In coming years, the wind-data tool will help Nebraskans detect any significant changes in wind-speed trends for specific locations.

“When I’ve thought about how the wind moves,” Lahowetz said, “it’s like a sea, like an ocean above us, and these things affect it and push it around. You get swirls and whirlpools — it’s kind of chaotic. And the closer you get down to Earth, the more chaotic it gets, with all the stuff it interacts with.”

The center will update the wind-data tool over time, with the long-term goal of covering seasons, multiple years and multiple months to enable comparisons.

“(The wind tool) will get better and better, and we’ll start to understand the evolution of wind over the whole United States over 30, 40, 50 years, as it goes on,” Lahowetz said. “That will help us understand how our climate is changing and how we can change the things we do that are important to wind.”