The future of U.S. agriculture is dependent upon research, innovation and collaboration, which together will lead to increased agricultural efficiency and sustainability, as well as development of foods designed to improve human health, U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue said Sept. 4 during a visit to Nebraska Innovation Campus.

“It’s universities like this that make that happen,” Perdue said.

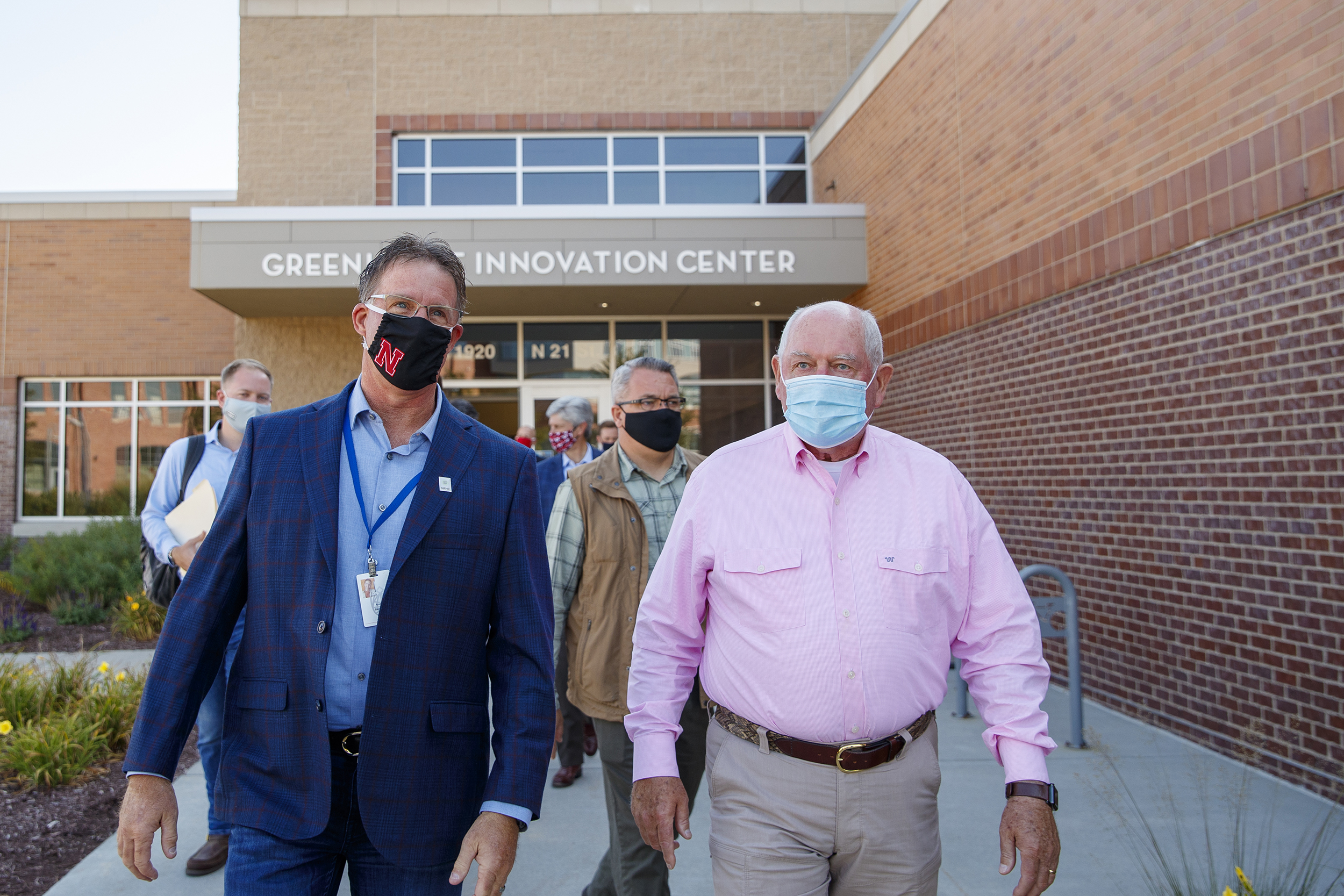

Perdue made the comments during a morning panel discussion. Nebraska Gov. Pete Ricketts, Rep. Jeff Fortenberry and University of Nebraska–Lincoln Chancellor Ronnie Green joined Perdue for the panel, which was moderated by Mike Boehm, NU vice president and Harlan Vice Chancellor for the university’s Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources. The panel discussion followed a tour of the Food Processing Center and Greenhouse Innovation Center, where the panelists heard from leading Husker researchers about their work.

During the discussion, Perdue described the USDA’s Agricultural Innovation Agenda, which calls for the United States to increase agricultural production by 40% while cutting its environmental footprint in half by 2050.

Research at Nebraska and elsewhere is already moving the United States closer to this goal, Perdue said.

“There’s a great ecosystem of innovation across this country,” he said.

But to increase both production and sustainability, government entities, universities, private companies and others engaged in research must work together, Perdue said.

Ricketts added that producers must be able to incorporate that research into their own operations. As an example, Ricketts cited plant imaging technology used in in the Greenhouse Innovation Center that had been retrofitted for use in a test field at the Eastern Nebraska Research and Extension Center near Mead.

“That’s real-world stuff,” Ricketts said. “What works in the lab, it has to work in the field.”

Additionally, Fortenberry said, rural communities across the nation must have access to broadband. Expanded broadband access will expand access to precision agriculture techniques. It will give producers and other rural residents the opportunity to work and take classes remotely and to access telemedicine and other services, he said.

Urban Americans are increasingly interested in understanding rural America, Fortenberry said. They want to know who grows their vegetables and produces their milk. This interest provides an opportunity for established farmers to diversify by adding a few acres of fruits and vegetables, and for young farmers without much land to begin their own operations.

“People want to know where their food comes from,” Fortenberry said.

At the same time, Fortenberry called for the development of the Farm of the Future, where researchers can experiment with cutting-edge technology and precision techniques to drive efficiency and sustainability.

Green said the Farm of the Future should be based at Nebraska.

The university has a long history of agricultural innovation that started with Charles Bessey, a renowned botanist, administrator and architect of the Hatch Act. That spirit of innovation continues today, Green said.

“We were in (agriculture) at the beginning, and it’s been our core ever since,” he said.

The university houses the U.S. Meat Animal Research Center in Clay Center, a world leader in the study of red meat animals. It is also home to the National Drought Mitigation Center, which helps producers, cities, states and other entities plan for and manage drought conditions, and allows producers affected by drought to access aid programs. These programs, both of which are partnerships with government agencies and other entities, have helped establish Nebraska as a leader in agricultural research that consistently ranks among the top 50 agricultural universities worldwide.

Innovation and collaboration have made America’s agricultural industry a world leader, Perdue said, and they’ll continue to lead to discoveries that change the way people think about food. Perdue specifically cited Nebraska’s Food for Health program, in which researchers are studying the relationships between specific foods and the gut microbiome. This is part of a larger field of study in which food is viewed as medicine or therapy, which Perdue said he finds particularly interesting.

It is a field that was unimaginable only a few years ago, and Perdue said he was looking forward to watching new breakthroughs in American agriculture unfold.

“There are amazing things coming that we can’t even dream about,” he said.