A space tool developed by University of Nebraska-Lincoln undergraduate engineering students is on its way to NASA’s Langley Research Center for its first structural test before being launched on a suborbital rocket in spring 2018.

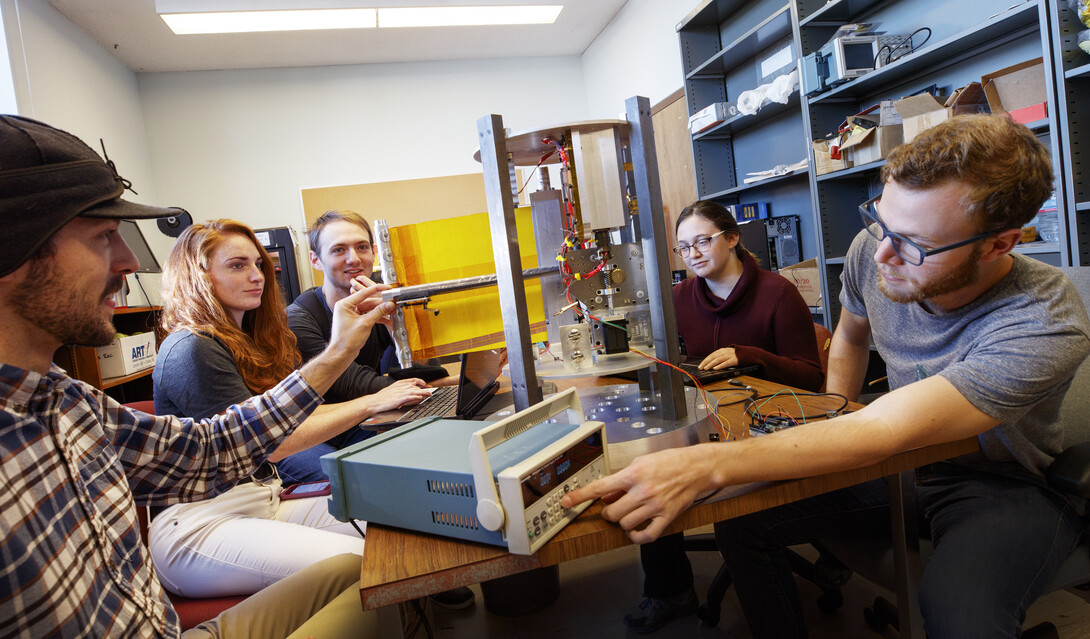

The student engineering team has been working on the project since August 2016, with some students devoting 20 hours a week or more on the device to enable satellites, rovers and other space vehicles to stow and deploy a lightweight boom to support a flexible solar cell panel.

The boom, its deployer, electronics housing and solar panel array were shipped to Virginia on Oct. 12 so that they can be displayed on a vibration testing table during an Oct. 21 open house celebrating Langley’s centennial. Thousands are expected to attend that event, which will give the public a rare chance to see the facility where Mercury, Gemini and Apollo astronauts trained. Among other things, the recently opened Katherine G. Johnson Computational Research Facility, named in honor of the woman whose story was told in the book and movie “Hidden Figures,” will be open to the public.

The vibration test will take place in the days following the open house.

It is the first critical test of whether the instrument can withstand the violent vibrations of a rocket launch, said project manager Amy Price, a mechanical engineering major from Columbus, Nebraska.

“We think there’s a high probability of success,” she said. The test gives the students a chance to find and correct possible problems before their project is sent to the Wallops Flight Facility, off the Eastern Shore of Virginia, for a rocket launch into microgravity in March 2018.

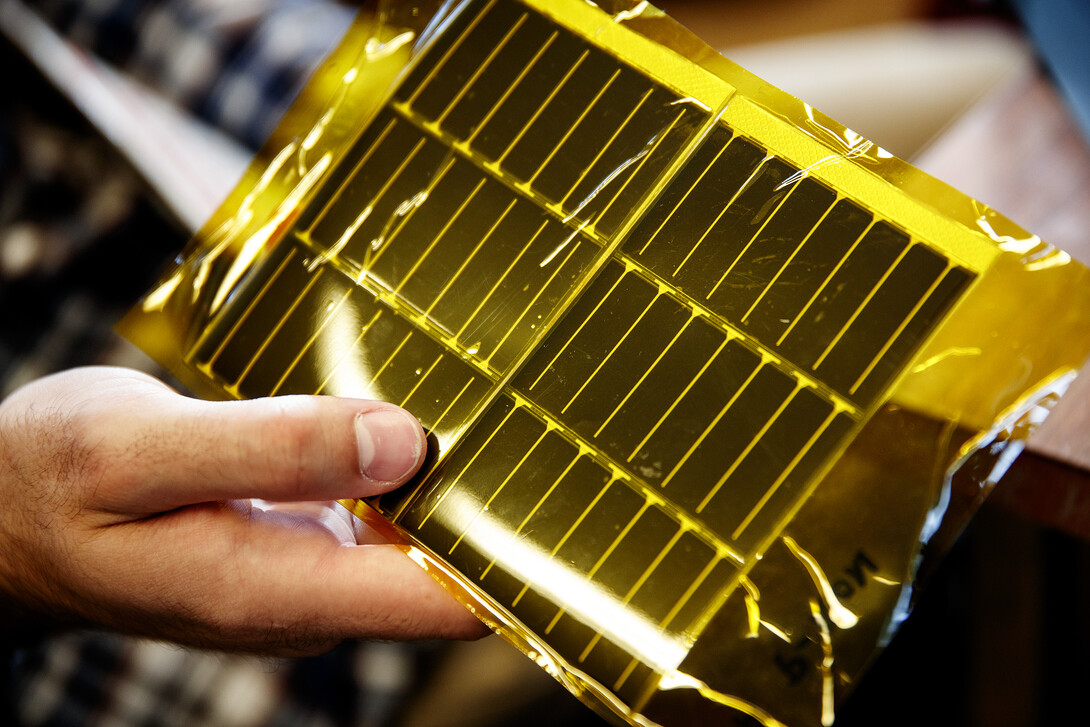

The mechatronic device features carbon fiber strips that unfurl into an 8-foot pole supporting a solar cell curtain. The carbon-fiber boom, designed and being patented by NASA engineer Juan Fernandez, works somewhat like a pocket tape measure. Two stacked ribbons have cross-sectional curves that arch open to create a rigid cylinder when the “tape” is extended. Flattening the curves allows the boom to be coiled back into its compact storage compartment.

Price and fellow team members Mike Cox, mechanical systems team leader; Elizabeth Balerud, special systems team leader; and Andrew Reicks, electrical systems team leader, spent marathon sessions in the Aerospace Laboratory in Nebraska Hall to meet their deadline for completing and shipping the device.

“It’s the equivalent of a part-time job,” Cox said.

Cox, a mechanical engineering major from Sutton, Nebraska, spearheaded the design and construction of the motor and gears that propel the device; Balerud, a mechanical engineering major from Columbus, worked on the solar panel and the integration between the electrical and mechanical components of the project; Reicks, an electrical engineering major from Omaha, headed the project’s computer and software components.

They lead a group of 15 to 20 students involved in the project, which is supported by an unusual $200,000 grant designed to give Nebraska engineering students a taste of what it’s like to work on a NASA engineering team. They’re learning to work across majors and to apply project management as well as technical skills.

Awarded through the NASA Nebraska Space Grant Consortium, the two-year grant is the largest amount given to the University of Nebraska-Lincoln during its 10 years participating in NASA undergraduate research programs. The Nebraska team was one of 47 nationwide chosen in 2016 to receive a share of more than $8 million distributed through the competitive Undergraduate Student Instrument Project (USIP) grant program.

Team membership has fluctuated as students come and go. Price, for example, is the third project manager, after two of her predecessors graduated. August McClenahan, a mechanical engineering student from Los Angeles, just joined the project after returning to campus from study abroad.

It’s very similar to what happens in the professional world, said faculty adviser Karen Stelling.

“One of the interesting things has been juggling student schedules through a two-year project,” she said. “Succession planning is part of what you do in the real world.”

The space boom project has given students the opportunity to work closely with engineers at Langley. Nebraska’s team is mentored by two NASA engineers who hold degrees from Nebraska, Justin Green and Matthew Mahlin.

Both Green, a 2009 graduate, and Mahlin, a 2011 graduate, said their exposure to NASA during their undergraduate years at Nebraska helped launch their aerospace engineering careers.

Mahlin is a former president of Nebraska’s Aerospace Club. He was active in RockOn and RockSat, other NASA programs where students launch various experimental payloads into microgravity from Wallops.

Green was a student intern at Langley during his undergraduate years.

Mahlin and Green helped the team connect with Fernandez, who developed his boom using similar concepts to those under consideration for the student project.

Stelling said the collaboration provides the students the opportunity to work with the high-tech materials Fernandez used, while giving Fernandez a chance to test his device in microgravity via the students’ payload space on a Wallops rocket. Langley is conducting the vibration test for the Nebraska team based on relationships developed with NASA by four Nebraska students who interned at Langley in summer 2017.

Faculty adviser Carl Nelson said he anticipates that Nebraska will continue to seek out collaborative projects with NASA in the future. The USIP project is part of NASA’s efforts to develop a future work force, he said.

“Faculty is hands-off on this project,” Nelson said. “We let the students do it. They have a real-life engineering problem to work on. They have to learn to function as a team and as engineers would in real life.”