Recent research conducted by the University of Nebraska–Lincoln’s Department of Agricultural Economics indicates crop insurance premium subsidies offered by the federal government have contributed to fewer and larger farms.

The current taxpayer-subsidized crop insurance program in the United States represents a culmination of a series of legislative acts, beginning in 1980 with the Federal Crop Insurance Act, followed by the Federal Insurance Reform Act in 1994 and the Agricultural Risk Protection Act (ARPA) in 2000.

These acts were aimed at encouraging producer participation through increased premium subsidies and enhanced coverage options. Increased subsidization was effective in increasing participation, as more than 90% of corn acres were covered by some form of crop insurance by 2020.

But counties in Nebraska experienced farm number decreases of 20% to 40% following the rollout of ARPA, according to the research.

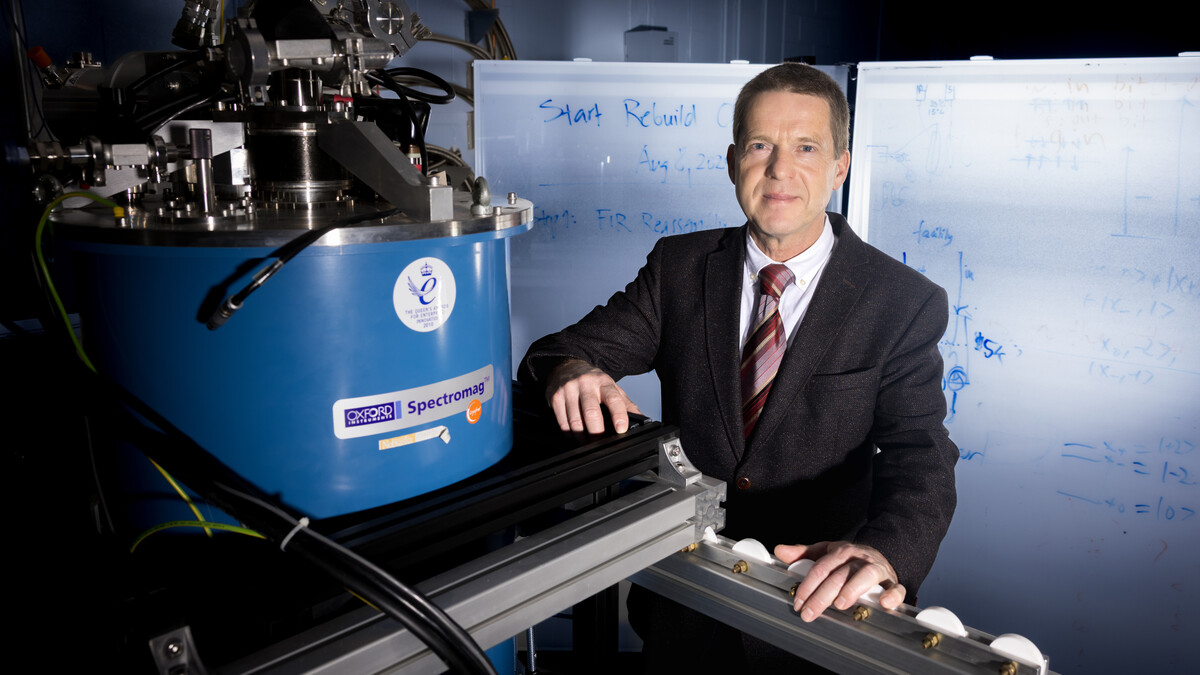

For 2021, premium subsidies in Nebraska for all crop insurance policies ranged from just over $36,000 in Hooker County to $10 million in Furnas County, with an average of just under $5 million. These subsidies can produce unintended consequences, according to Cory Walters, associate professor of agricultural economics.

“Some farmers know the system and can take advantage, using returns to beat up on their uninformed neighbor,” Walters said.

But the identification of these unintended consequences can be useful to policymakers in rethinking future crop insurance policy design.

One unintended consequence is farm consolidation, whereby farms are bought out using rents acquired from subsidized insurance and consolidated into larger farms. A legislative rise in premium subsidies, as was the case through ARPA in 2000, raises expected returns to participation in crop insurance. To the extent that an increase in expected returns induces individual participating farmers to increase crop supply, they may collectively see their benefit from insurance offset by declining market revenue and non-participating farmers may incur losses, as well. That is because the increase in aggregate crop supply, induced by participation in subsidized insurance, results in declining market prices.

Walters said this study provides a strong theoretical link between crop insurance subsidization, market prices and output, and long-run market participation.

“How these factors interplay in the real world has not been addressed,” he said.

Along with Walters, the research was conducted by Taylor Kaus, a master’s student in agricultural economics, and Azzeddine Azzam, Roy Frederick Professor of Agricultural Economics.

A full summary of the findings is available in a recent Cornhusker Economics article published by the Department of Agricultural Economics.