Like many children around the world, Sangjin Ryu was a big fan of sci-fi movies, television shows and comic books.

But it was only after finishing graduate school in the United States and joining the faculty in the University of Nebraska–Lincoln's College of Engineering that Ryu understood he had a second calling: to use his love for those forms of pop culture to help people around the world grasp complex engineering principles.

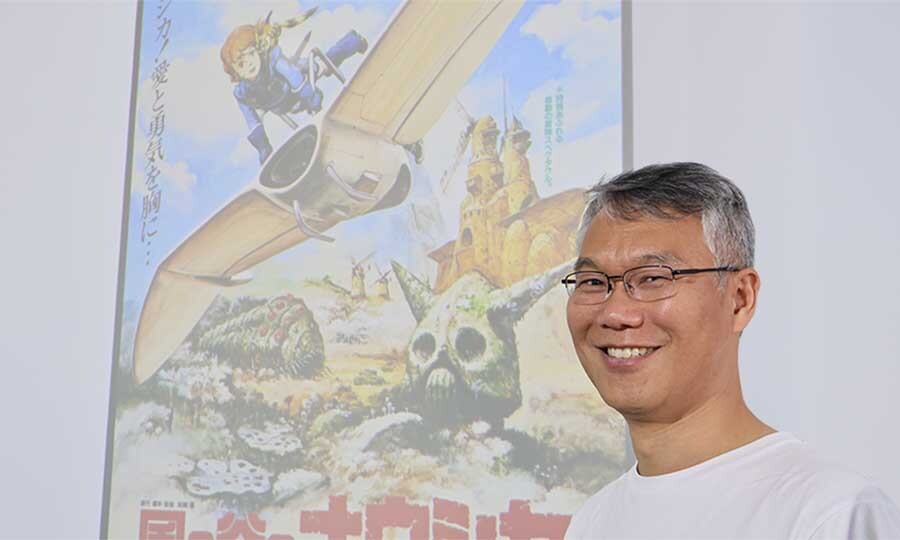

That's how he developed his educational alter ego, "Professor Otaku," who uses examples of popular animation and movies in his teaching.

"Otaku is a Japanese word that means a person who has a strong interest in anime (typically, television shows or movies), manga (comic books, graphic novels, etc.) and other things in that genre," said Ryu, associate professor of mechanical and materials engineering and a native of South Korea. "Since I was a child, I have been otaku. I always liked Japan and their (pop) culture, particularly robots and mechanical things in animation or movies.

"Then, I studied mechanical engineering and had this thought that someday in my future, when I become a teacher, I might use an approach to explain mechanical engineering using Japanese animation."

After joining the Nebraska Engineering faculty, Ryu began teaching classes in fluid mechanics, relating the scientific principles that explain how things such as air, energy and fluids move and are influenced by the forces that act upon them.

It's a complex field, and Ryu quickly realized he needed to do something unique to reach students struggling with the typical lecture format.

Enter Godzilla.

"At home, late at night, I was watching the first Godzilla movie, and something occurred to me," Ryu said. "It was the first scene where Godzilla appears from the ocean. I noticed that the water flow around this emerging, gigantic monster didn't look realistic — the water is dripping from his body like it does from mine when I take a shower.

"I thought that this is related to dimensional analysis or something that I will be using to teach later in the semester. Then, I thought, 'What if I show this clip in class? Would that motivate the students about what they're going to learn?'"

So, Ryu showed the movie clip to his class in the Othmer Hall auditorium, and asked if something seemed strange about it from a scientific perspective. The students were becoming more engaged.

"It was a very deep room, where students and teachers can easily become disconnected. And that's what happened in my class," Ryu said. "But I showed them the clip, and suddenly the students weren't as sleepy. After a few seconds, they started giving answers. Then, I asked if the water flow around this 80-foot monster was realistic and how, as engineers, they could improve the scene."

Ryu still uses those examples in his classes, including asking a class reviewing for a final to take what they have learned about lift and aerodynamics to determine whether Möwe (a fictional, dove-shaped, jet-powered glider from the anime "Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind") would be able to fly in the real world.

After debate, Ryu showed a YouTube video of a real-life version of the aircraft that did, indeed, fly.

Mechanical engineering senior Matthew Brown said Ryu's teaching technique helped him to better understand what was being taught.

"It's really interesting when we're learning some of the theories in class, developing that theory in our lecture notes, and then Dr. Ryu will present an application that is shown in anime," Brown said. "It takes some of what you might think is a boring theory and puts it into something that's not necessarily a real-world application but allows you to apply it."

The classroom successes motivated Ryu to take a more scholarly approach to what he was doing. He consulted with Mark Griep, professor of chemistry and co-author of a book — "ReAction! Chemistry in the Movies" — that examines how chemistry is portrayed and used on the silver screen. Griep also uses movie examples in his teaching.

Ryu also collaborated with graduate student Haipeng Zhang and Engineering and Computer Education Core's Tareq Daher and Markeya Peteranetz on a project researching this educational technique. The team's paper was published in the April 2020 edition of the Physics Teacher, an American Institute of Physics journal focused on education and, Ryu said, became the journal's second-most downloaded paper that year.

That led to more worldwide recognition, including Ryu being published in a journal in his native South Korea, being invited to deliver virtually a keynote address for a national STEM conference in the Philippines and having scholars use his work to inspire their own educational techniques and research.

In April, the Journal of Geek Studies published Ryu's paper "Are Japanese anime robots isometric or allometric?" and noted the author's secret identity: "He is also known as Professor Otaku for his informal lectures on mechanical engineering using examples found in Japanese animation."

Those informal lectures at home in Nebraska are mostly to general audiences, Ryu said, including a series of lectures in the Kawasaki Reading Room, which shares Japanese culture, art, language and history to the university and the extended community.

"I'm always changing those examples, for both those talks and my classes. I try to use the database in my head, creating my own list of favorite examples from old and new animation," Ryu said.

"It kind of gives me a good excuse to watch the more recent animation at home."