Everyone should take a course in climate change 101, a widely recognized expert on public opinion of climate change said March 10.

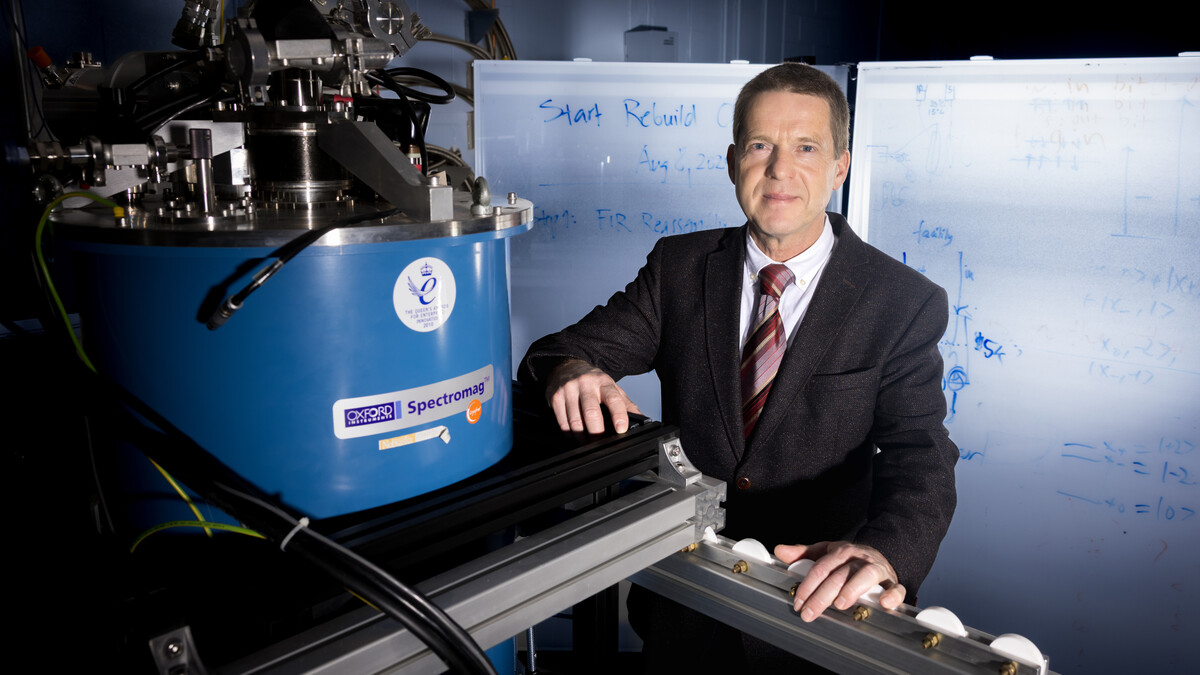

Anthony Leiserowitz, director of the Yale Project on Climate Change Communication and research scientist in the School of Forestry and Environmental Studies at Yale, spoke as part of the Heuermann Lectures in the Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Leiserowitz conducted the first empirical assessment of worldwide public attitudes toward global sustainability and researched these values in the United States, individual states and municipalities, India and with the Inupiaq Eskimo of Northwest Alaska.

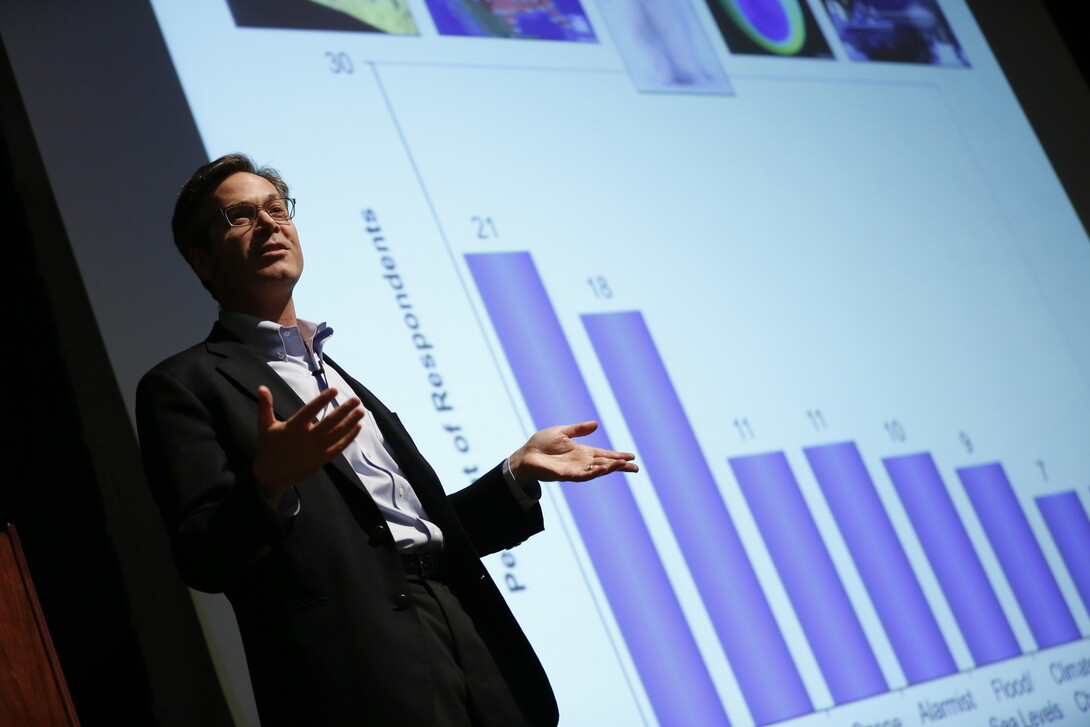

Together with Edward Maibach, director of the Center for Climate Change Communication at George Mason University, Leiserowitz developed the concept of the “Six Americas,” which segments the U.S. population based on the public’s attitudes and beliefs toward climate change. The six groups are “the Alarmed” (13 percent), “the Concerned” (31 percent), “the Cautious” (23 percent), “the Disengaged” (7 percent), the “Doubtful” (13 percent) and the “Dismissive” (13 percent).

The facts are actively interpreted by these different audiences, who construct their own understanding in accordance with what they already “know,” value and feel. Each audience needs tailored engagement strategies and clear messages, repeated often, Leiserowitz said.

The number of Americans who think climate change is not real continues to decline but a well-funded and documented “denial industry” uses strategies similar to those used to try to discredit the link between tobacco and human health in which “doubt was the product,” he said. One of the reasons for doubt about global warming is that it is invisible.

“Carbon dioxide is pouring out of buildings, tailpipes and people’s mouths. We are standing in a volcano of carbon dioxide rising out of the atmosphere,” Leiserowitz said. “It is the same in every city but we can’t see it so it is out of sight, out of mind.”

Leiserowitz listed what he calls “the big five facts in 10 words” that people should know about global warming: “It’s real; it’s us; it’s bad; scientists agree; there’s hope.”

Only one in 10 Americans know that 90 percent or more of climate scientists have concluded that human-caused global warming is happening, and only 9 percent of Americans have any idea of that percentage, he said.

Research by Leiserowitz and his colleagues indicates that about 71 percent of Americans believe global warming is occurring but only 45 percent are worried and only 11 percent are “very worried.”

No one associates the impact of global warming on human health such as allergies, asthma and diseases, he said. “People become more engaged when they realize it’s about them.”

Politics is another factor. Democrats and Republicans agreed on global warming in 1997. Currently it is the most polarizing issue.

Despite the fact that global warming was next to last of the top priorities for the President and Congress in 2014, a majority of Americans support funding to make roads, bridges and buildings more resistant to extreme weather; funding more research on renewable energy sources; providing tax rebates for consumers who buy energy efficient vehicles or solar panels; regulating carbon dioxide pollution; and requiring electric utilities to produce at least 20 percent of their electricity from renewable energy resources even if it costs the average household an additional $100 annually.

Leiserowitz’s suggested course of action: Communicate the scientific consensus on global warming. Connect climate change to our lives and values, especially health. Explain extreme weather in the proper climate context and emphasize that global warming is solvable.

“Americans are beginning to connect the dots between climate change and extreme weather, jobs, national security, faith and values, making it here and now,” he said.

Heuermann Lectures are made possible through a gift from B. Keith and Norma Heuermann of Phillips, longtime university supporters with a strong commitment to Nebraska’s production agriculture, natural resources, rural areas and people. The lectures focus on providing and sustaining enough food, natural resources and renewable energy for the world’s people, and on securing the sustainability of rural communities where the vital work of producing food and renewable energy occurs.