A Latino defendant convicted of murder who is poor is more likely to be sentenced to death by white jurors, a new study shows.

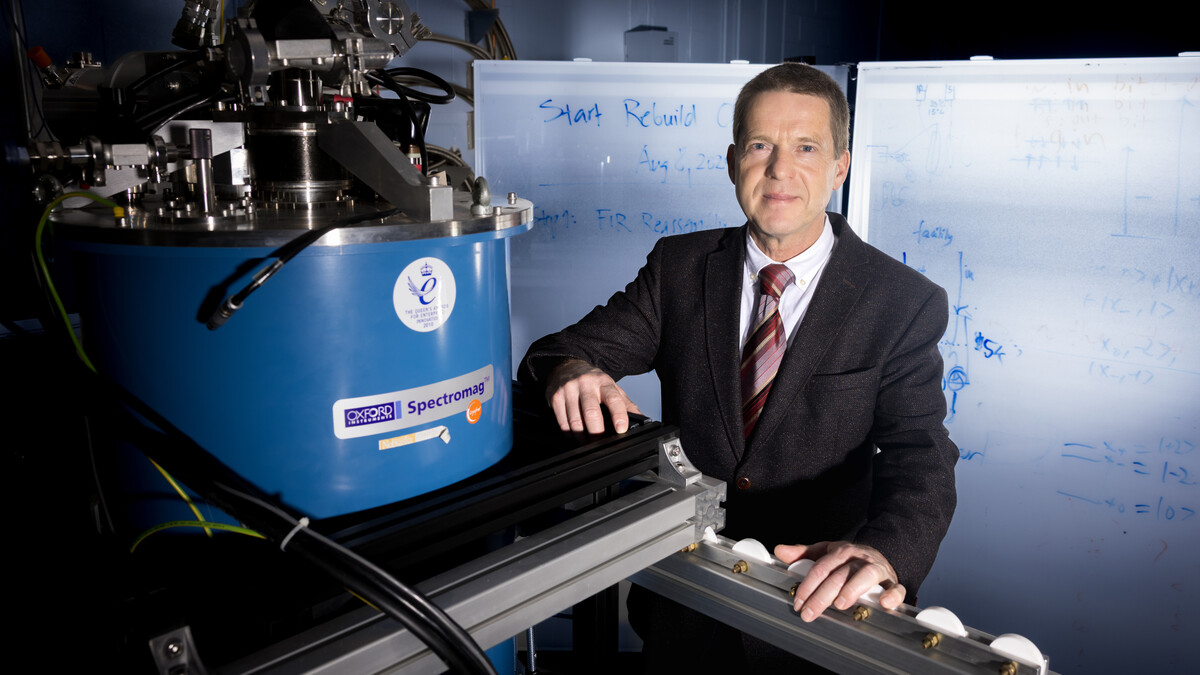

The study was conducted by UNL psychology and ethnic studies professor Cynthia Willis-Esqueda and her colleague, Russ K.E. Espinoza of California State University, Fullerton, who earned his doctorate at UNL.

More than 500 white and Latino people called for jury duty in a southern California courthouse participated in the research, and they were asked how they would decide a hypothetical murder case.

Based on an actual incident in which a man was sentenced to life in prison for killing his wife and her friend, the circumstances of the case were altered by researchers to create eight different scenarios depending upon whether the defendant was white or Latino; whether he was rich or poor; and whether mitigation evidence was strong or weak. Each mock juror reviewed one hypothetical situation.

Published online this week in the journal Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, the study found that white jurors were more likely to impose the death penalty in cases where the defendant was Latino and poor. They were most likely to impose it if a Latino defendant of low socio-economic status had few mitigating circumstances.

“If the defendant was of low socio-economic status and Mexican-American, he received the death penalty more often, compared to other conditions,” Willis-Esqueda said. “We were really saddened by that. They could have chosen an alternative sentence, such as life in prison without possibility of parole.”

Latino mock jurors did not show the same strong correlation between ethnicity and socio-economic status when they imposed the death penalty.

The researchers described their findings as a form of “aversive racism.” That is an indirect form of bias in which people realize it’s offensive to judge someone by their skin color and use other reasons to reach a biased decision.

The researchers said the study has important implications for the criminal justice system. It makes it even more important for defense attorneys to submit mitigating evidence on behalf of Latino defendants. It also raises questions whether potential jurors should be educated about ethnic biases in decision-making.

“Perhaps the introduction of the history of bias toward Latinos in the legal system is warranted,” they wrote.

The study participants, who were interviewed after they had been dismissed from an actual jury pool, were given mock court documents describing the crime, including a small mug shot of either a white or Latino defendant. The photos were pre-screened to ensure they did not differ significantly in terms of attractiveness, aggressiveness, or apparent income status. The case included overwhelming evidence of the mock defendant’s guilt. In half the cases, the defendant was described as high socioeconomic status – a college graduate and business owner who lives in four-bedroom home in the suburbs and who drives a Mercedes. In the other half, the defendant was described as an unemployed high school drop-out who is behind on his rent at his boarding house.

Half the hypothetical cases included strong evidence of mitigating circumstances that might lessen the defendant’s culpability for the crime – he was a victim of child abuse, had been in and out of group homes as a child, and had suffered from various mental problems. In the other half, the defendant had weak mitigating evidence – he was said only to have suffered a bout of depression at the time of the crime.

All of the mock jurors were “death-qualified,” meaning they had to be willing to impose a death sentence before they could participate in the study.

The white jurors sentenced about half of Latino defendants with weak mitigating evidence or low socio-economic status to death. They sentenced about one third of European American defendants with low socioeconomic status to death and about one-fourth of European-American defendants with weak mitigating circumstances to death. They were more likely to find low socioeconomic Latino defendants to be vicious, intentional, and more to blame for the crime.

Latino jurors, however, imposed the death sentence only about one in four times, regardless of the defendants’ ethnicity, socioeconomic status or mitigating evidence.