Timothy Schaffert speaks in a mild scratch, vocal chords seemingly rubbed in cornmeal, his voice quiet for sentences at a time before spiking in volume for a word, a phrase, then dropping back down to his above-a-whisper.

He laughs in unexpected moments: discussing the cultural and psychic weight, invisible and ineffable as such forces are, that he must have borne as a young boy in rural Nebraska who would grow into a gay man — the laugh landing square on the word “oppression,” without resentment.

It was Aurora, Nebraska, after all, a town of ~3,000. It was the 1970s, too. An unlikely origin story, maybe, for a queer writer whose historical fiction would come to be lauded by The Oprah Magazine, whose teaching and mentorship would help sustain the historic legacy of LGBTQ literature at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln. But then, Willa Cather was raised in Red Cloud. And she had even mentioned Aurora, once, in “A Lost Lady.”

Still, an 80-acre farm of semi-arable heartland lay beyond the tremors of the Stonewall uprising that had lifted gay rights into the national consciousness from the cosmopolitan counterculture of Lower Manhattan.

“I don’t know that I necessarily knew the extent of my difference,” said Schaffert, now the Susan J. Rosowski Professor of English and director of creative writing at Nebraska.

It would be more than 25 years before he would come to fully identify as gay, before his future husband would ask him on a date from an AOL chat room of the 1997 internet. In Aurora, in the ’70s, he was just the odd kid who drifted toward the wrong toys and recessed with the girls. There was no closet, let alone coming out. He liked writing, would become a writer, but didn’t yet have the words that might have added color and context to the black and white of his childhood.

“It’s funny: I remember growing up feeling like people identified things about me before I even knew them about myself,” he said. “I got mistaken, I guess is the word you would use, for a girl a lot. It was kind of embarrassing to me, because there was this sense that it was embarrassing to the people around me — that there were expectations of boy children, and there were expectations of girl children, and they just didn’t intersect.

“Sometimes I think, when you grow up gay, you do end up learning about yourself through your bullies. They’re the ones who decide who you are and who you’re not, and they’re bold about articulating that for you.”

When fragments of queer life did pierce Schaffert’s bucolic bubble via talk shows or local broadcasts, it was often deemed a “social problem.” Later, while attending Aurora High School with mostly the same 100 or so classmates he’d known since kindergarten, queerness came bundled, always, with news of the AIDS crisis.

“Even though I recognized queer life and could relate to it,” he said, “it all seemed like something that was not available to me, or would ever be available to me.”

That seclusion stemmed not just from distance, but time. Schaffert’s father hailed from Aurora, his mother nearby. As he approached graduation, he felt anchored to the place by the presumption that he’d remain there. Maybe he’d just continue working at the local drugstore. Maybe he’d eventually own the drugstore. No risk in that.

Ultimately, though, he cast his eyes 75 miles due east, to Lincoln, enrolling in the fall of 1986. He majored in journalism, switched to advertising, back to journalism. Again, not quite fitting, “just flailing and frustrated.”

“I didn’t get that good of grades, and a lot of that was because I would just not go to class,” he said. “I would go to the movies instead.”

“Blue Velvet” and “Something Wild” hit theaters within months of his arrival. “Fatal Attraction” and “Moonstruck” arrived in the fall semester of the following year. Schaffert gave in to “The Last Temptation of Christ” in ’88. “When Harry Met Sally” met Timothy in the summer of ’89. Downtown Lincoln of the late ’80s overflowed with multiplexes, and Schaffert availed himself of “that whole big movie theater experience.”

But he had also enrolled in creative writing courses and embarked on a 24-credit concentration in English that was nourishing his soul, and rewarding his sensibilities, in ways that journalism was not. If journalism was hard-hitting documentary, he was really more into the fictional stories he was absorbing through the silver screen, from the darkness of a theater. Plus, he was receiving encouragement, and his writing recognition, from the likes of Gerry Shapiro, Judy Slater and other English faculty who convinced him that, yes, a career in creative writing could be had, and yes, it could be his, if he wanted it.

So, at the last conceivable moment, already possessed of nearly four years in journalism training, he became an English major, sticking around for a fifth to claim the degree and diploma. At the time, he was unaware of the Sex Roles and Literature course taught by Lou Crompton, of how Crompton had crafted and co-taught a course on LGBTQ studies all the way back in 1970 — two years after Schaffert’s birth, a mere one after Stonewall. He did know one of Crompton’s colleagues, Barbara DiBernard, who was out and teaching a women’s literature course whose reading list was loaded with lesbian writers.

“She spoke openly about that, and she spoke openly about sexuality around the world,” Schaffert said. “I learned so much from her and through that class.”

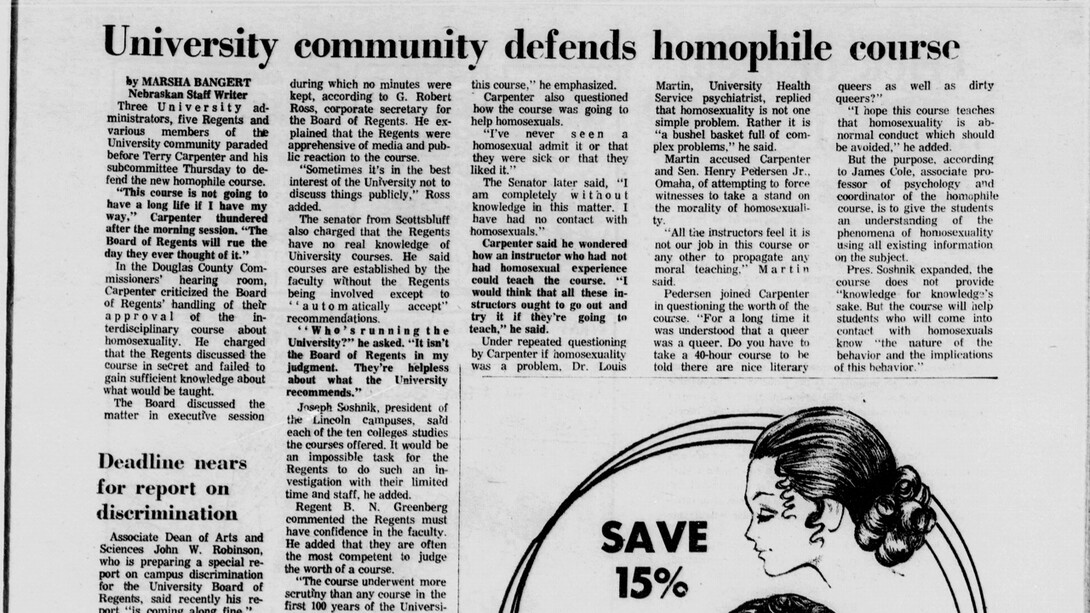

Some at the university and across the state, though, were maintaining the same anti-gay crusade that Crompton had faced in 1970. Schaffert recalled the controversy raised over a trifling percentage of student fees potentially going to support the Committee Offering Lesbian and Gay Events, which was eventually denied that funding by the student government in 1988.

He conceded that he “wasn’t particularly enlightened” about the LGBTQ movement then, didn’t have the sense of identity, or even the capacity for self-identification, that he would see and so admire in subsequent generations of English students at Nebraska U.

“I wasn’t in the circles where I was really meeting other students who were gay. And I liked the girls I was dating,” he said, his laugh re-emerging. “I wasn’t tortured in that regard, and there was a lot that I was able to express through my creativity, too.

“I think that was another reason I was really drawn to writing: I could get into the sensibilities of a woman and the sensibilities of a man. I was thinking a lot about the particularities of gender in terms of the characters themselves, and sexuality, without necessarily writing about it directly or thinking about it in terms of my own life.”

*******Schaffert was barely familiar with the concept of an MFA program when he finally accepted English as his major. Yet by the time he graduated with his bachelor’s, excerpts from his early attempt at a novel had earned him a couple of national awards.

Despite already coming to grips with the time-honored destitution of the young writer, he headed for the University of Arizona, where he spent four years earning his MFA in the desert. There he became acquainted with the writerly tradition of false hope, too: A literary agent in New York reached out for a copy of his novel, loved it, but had to let it go amid maternity leave.

He hammered away on short stories that would become the bones of his first two published novels, both of them set in the desert. Later, on the advice of some editors, he moved them to the familiar mise en scène of the Cornhusker State. After a year of going broke in New York and contending with a chronic intestinal disease, Schaffert joined his novels back in Nebraska, the prodigal returning for six months to the 80 acres outside Aurora.

Soon he was settling into Omaha and, in his late 20s, the concept of himself as a gay man. He managed to find one of the few chat rooms specific to gay men in Nebraska, where he met Rodney. By 1998, they were living together.

“So then you’re just kind of who you are,” he said. “I didn’t really discuss it with everyone in my life. I probably was still in the closet to some degree.

“When you’re gay, especially if you grow up in oppressive times, everything becomes a kind of negotiation or, at least, some level of navigation through your life: How much do I actually have to say? I think there was a part of me that also just resented the notion that I had to talk about it, that I had to tell anybody, that it was anybody’s business, for one thing, or that I could even necessarily articulate every aspect of it.”

The crystallization of his personal life belied the freelancing flux of his professional. He got a gig writing recruitment brochures for universities and colleges around the Midwest. He interviewed professionals to learn about their day-to-day, writing up career guides that would wind up in encyclopedias that would wind up on library shelves.

“Ironically,” he said, “I had no career, but I was writing these career guides.”

He went to work for a couple of alternative weekly papers in Omaha, even penning movie reviews for them. Throughout it all, though, he continued to write his fiction, getting his first novel published in 2002. He continued to battle his disease, too, which had progressed to bleeding ulcers. (“Your body thinks that everything you consume is poison, so it attacks. I have a complicated relationship with food.”) Then a drug cocktail temporarily silenced the ulcers and inspired the insomnia that would launch an annual, ongoing literary tradition.

“I only had the good side effects, which is that I always just felt full of energy,” he said. “I didn't feel like I needed sleep, so I was up all night, and I would do these haywire projects in the middle of the night. One night, I decided, ‘Oh, I'm going to start a literary festival!’ So I started contacting people that I knew, and I was reaching out to the community and seeing where I could have it and what it might be. Then I went to bed, and the next morning, I’m like, ‘What did I do?’ But at that point, emails were coming back, and there was interest.”

That interest would become the (downtown) omaha lit fest, which Schaffert directed from 2005 to 2015. And with a new miracle drug knocking his disease into remission, his mentors in Lincoln urged him to take on an adjunct position that had him teaching a night course at Nebraska U. Within two years, he was also directing the Lincoln-based Nebraska Summer Writers Conference.

Schaffert had been away for 15 years, but with roughly a dozen faculty from his undergrad days still stationed in the Department of English, the place felt “profoundly familiar.” There were changes, naturally. The course previously known as Sex Roles and Literature had just been renamed Introduction to Lesbian and Gay Literature, because, as Schaffert put it, “They felt that they should call it what it is.” But Barbara DiBernard was still there, having taken on the teaching of the course from the retired Lou Crompton.

Back in the late ’80s, Schaffert remembered, DiBernard would sometimes encounter objections when teaching about lesbian authors. Should the courses be kept off transcripts, some wondered at the time, to protect the students who took them? By the mid-2000s, having returned as an adjunct and asked DiBernard for the honor of teaching the introductory course, Schaffert found that her persistence had outlasted those objections.

“When I began teaching it, it was a foundational course, very popular,” he said. “A lot of that struggle was really fought by my predecessors, to my advantage, so that I could go into the classroom and didn’t really have to worry about any consequences.”

In teaching the intro course, and later a 300-level counterpart added by the department, Schaffert felt himself grasping a baton that DiBernard had relinquished to him, and Crompton to her.

“Having been a student here, I do feel like that has greatly informed my sense of commitment to these courses and this programming and the history of it all,” Schaffert said. “There’s always a risk of courses or an entire curriculum or a program disappearing when its faculty retires or moves on. When Lou Crompton taught his first (LGBTQ) course in 1970, that was through his own initiative. Nobody had said to him, ‘Lou Crompton, you really need to develop a course on homosexuality.’”

Far from it, as Schaffert would learn. Within a few years of teaching in the department, Schaffert had become familiar with its claim: Crompton’s Proseminar in Homophile Studies, which was offered in the fall of 1970 and cross-listed as English/Sociology/Anthropology 271, was the first interdisciplinary LGBTQ course in the United States. As part of his case for offering the course, Crompton had compiled a list of other LGBTQ courses, elsewhere, that had either come before or were being introduced around the same time. Curious, Schaffert began Googling some of the courses on that list.

“Everything just kept leading me back to Lou,” Schaffert said. “I kept finding that any reference to LGBT courses that existed before Lou’s came from Lou’s own materials.”

Schaffert found himself playing amateur historian, following the late Crompton’s trail by seeking out evidence that prior courses had, in fact, existed. His research led him to conclude that the entries on Crompton’s list were no more than snippets of curriculum, possibly colloquia or presentations. As Schaffert sees it, Crompton’s apparent efforts to inflate their stature, and to downplay the novelty of his own, speak to the realities of his era.

“I think that was because he needed to provide a kind of evidence to the university that we weren’t the first,” Schaffert said. “I don’t think it was advantageous to him and the development of the course for it to seem like it was the first of its kind, that we were breaking ground in this way.

“I feel pretty confident that Lou’s course was the first on homosexuality in the U.S. to be offered through a regular course catalog. It certainly wasn’t the first course that incorporated homosexuality as part of its discussion. But I think it was the first in many ways, the first in terms of how the course was designed, how it was viewing homosexuality.”

And it’s fueled his enthusiasm for teaching the early examples of LGBTQ literature, the writing that predated public discussion of homosexuality and the modern language surrounding it. In some cases, delving into the once-hidden lives of writers now known or presumed to be gay “makes students nervous,” he said, worried that it represents an invasion of privacy. It’s an instinct that Schaffert understands and appreciates, especially among students raised in an era defined in part by its surveillance.

But the value of that literary archaeology, he believes, is legion.

“It’s an ongoing process of discovery,” he said, “where we’re looking at the past and excavating queer lives from periods of history when the stories couldn’t be told, and people couldn’t express themselves freely and openly, but in other ways left clues and some insight into who they were and how they were.

“So there is an important process of claiming those people as our own, as queer. That also builds the foundation for LGBTQ literature, so that it’s not just some new development of the late 20th century.”

For all he’s dedicated to honoring the past of queer literature, Schaffert is focusing, too, on its future. He’s mentored numerous queer writers, among them emily danforth, whose debut novel, about a teen girl forced into conversion therapy, inspired a Sundance-winning film. In partnership with the University of Nebraska Press, he recently co-founded the Zero Street Fiction series, the first of its kind to publish new queer fiction.

“We’ve had an overwhelming response,” he said.

That response signifies progress, he knows, the distance traveled by Crompton and DiBernard and the countless, sometimes closeted writers who preceded and followed them. He also knows, cannot ignore, the incessant ignorance and hate and political posturing that lacks “a foundation in truth or sincerity or really any kind of reflection of how society wants to think of itself.” He worries for the queer children raised in communities that still treat difference as defect.

“It can be frustrating, because you feel like there’s something you need to do directly; you need to do something immediately; you have to act.

“At the same time,” he said, “I work at a university where there’s a commitment to complex thought. So I can celebrate this 50-year history. I can teach the courses that I want to teach. I can write the work that I want to write.”