· 5 min read

REACH suicide prevention training educates campus on ways to engage

Even though the conversations can be uncomfortable, a Big Red Resilience and Well-Being program is encouraging Huskers to talk about suicide as a way to create “a campus culture of caring.”

The training program — called REACH — educates people on practices to engage with others in the community who are struggling with suicidal thoughts. Since it was first offered at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln in 2018, the program has trained more than 7,000 members of the campus community on ways to recognize warning signs, talk to those at risk, and lessen the stigma associated with suicide. The training walks participants through five steps for engaging with people in distress and guiding them toward professional help.

“This is mental health CPR,” said Spencer Godina, REACH trainer and computer science and mathematics major from St. Charles, Illinois. “You may not be able to solve the problem, but you know who can and you can sustain the situation until better help can arrive.”

Big Red Resilience and Well-being offers the training by request to student organizations, faculty, classes or other groups. They also hold public trainings around once a month. They completed 35 trainings during the fall 2023 semester.

Big Red Resilience and Well-being also offers resources like pop-in peer listening sessions where students can connect with well-being ambassadors, Big Red Pawp-Up events with therapy dogs and the Husker Pantry.

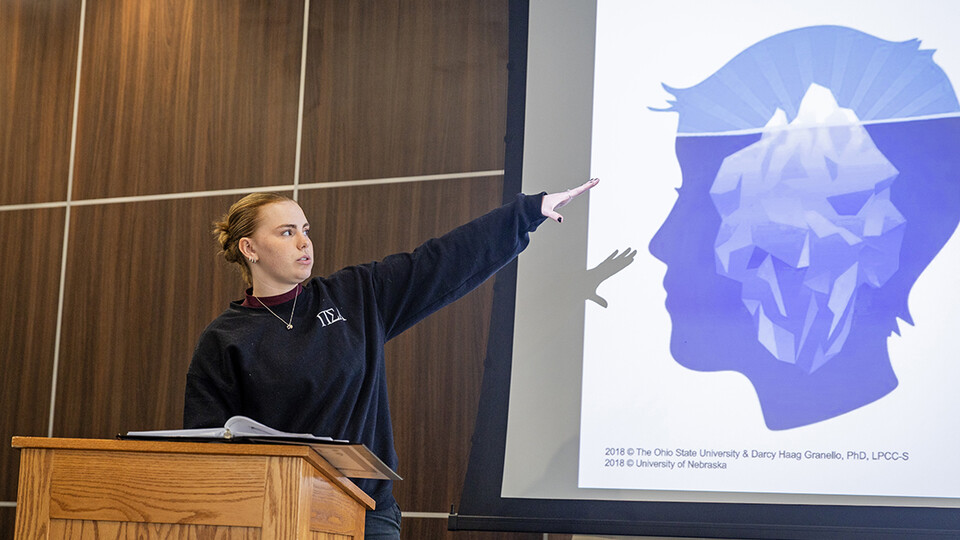

In the training, the first step is to “Recognize the warning signs,” including an explanation of some high-risk groups. In a college setting, students who are male, older, international, returning veterans and members of the LGBTQ+ community are at higher risk. Situational triggers like public embarrassment, relationship or job loss or isolation can also be risk factors.

Some behavioral warning signs are withdrawing from typical activities like time with friends or going to class, increased substance use or giving away possessions. The person might even make direct or indirect statements about wanting to end their life.

Godina said it’s important to keep an eye out for these signs and step in early when they arise.

“Catching things early can prevent that snowball from building and that weight from building up on someone’s shoulders,” he said. “You don’t necessarily want to show that weight to the outside world…By the time you notice the cracks in someone, they’ve been hiding that pain for so long already.”

The next step is to “Engage with empathy.” A trainer gives examples of things one can say and other things they should avoid saying. For example, if someone is in crisis, don’t offer advice because you are not a mental health professional, but do let them know you want to get them help. Don’t interrupt them as they explain their feelings, and check in on them periodically after the conversation.

The training also encourages people concerned about someone in their life to next “Ask directly about suicide.” It’s important to use the precise and clear language and not dance around the subject. Godina said asking can make people reflect on where they actually are mentally and can open their eyes that they need help.

If the person does express they’ve been contemplating suicide, one should “Communicate hope,” or reminding the people they are not alone in their feelings, that there are people who want to help and mental health resources available to them.

The final step is to “Help access treatment.” Someone can offer to take the person to Counseling and Psychological Services or call a counselor’s office to make an appointment. They should speak in definitive terms that the person is going to get help and not ask if they want to get help. In crisis situations, this could mean trying to keep the person on the phone until help arrives.

Participants in the training also practice having these conversations during a roleplaying exercise.

Amanda Hogin, an advertising and public relations major from Marin County, California, signed up for the training because of past personal experience. As a freshman, Hogin struggled with anxiety and other mental health issues like shame from bad grades, ultimately leading to her own suicidal ideation. Hogin accessed CAPS and other mental health resources during that time. She said looking back she realized there were a lot of people in her life who wanted to help, so she wanted to be a resource for others going through similar feelings.

“I want to be the outlet to help other people because I was in their position,” she said. “I want to be the best I can for other people.”

Hogin said she was shocked by some of the statistics but her biggest takeaway was that it’s OK to speak about suicide explicitly.

“It’s OK to ask directly about suicide, not walk around it,” she said. “A lot of people do that because they’re afraid of the answer.”

Godina said there are resources in every medium imaginable, from in-person counseling to texting hotlines, and identifying a problem and setting someone on that path is the first step toward their recovery.

“While this is maybe a problem you hear about in the shadows, it’s one that exists on UNL’s campus and one we’re working really hard to combat,” Godina said.