Slavery has often been painted in broad strokes in history books and narratives, giving little attention to slaves’ daily lives and social networks. For more than a century, these broad strokes have made it nearly impossible for their descendants to trace their heritage.

An ongoing collaboration between University of Nebraska-Lincoln and University of Maryland researchers, however, is filling in some of the missing pieces.

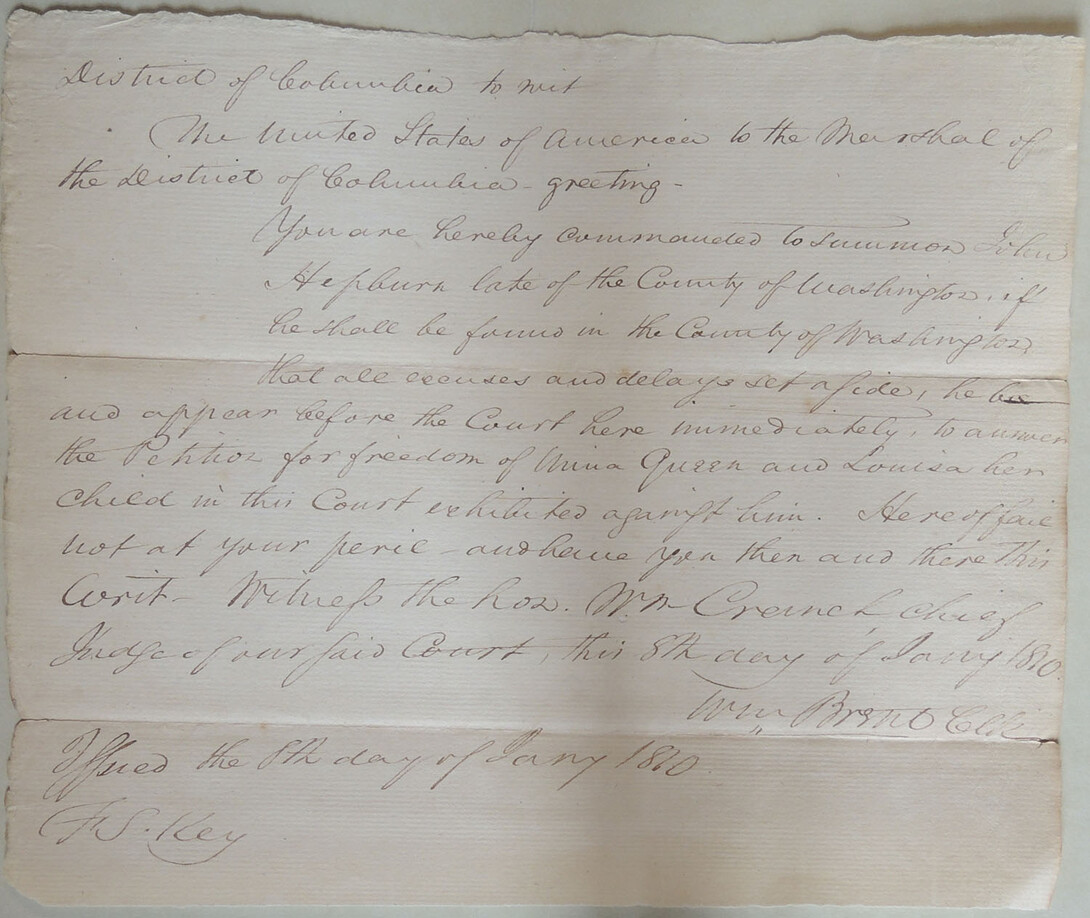

The O Say Can You See: Early Washington, D.C., Law and Family Project is digitally archiving petitions for freedom lawsuits that were filed in the U.S. Circuit Court in the nation’s capital from 1800 to 1862, up until the Emancipation Proclamation that was issued Jan. 1, 1863. The court records add texture to stories about slaves, the slaveholders, and the families and power brokers of early Washington.

The project has quickly grown to host more than 1,200 documents from about 250 petitions for freedom. In the next year, those numbers will grow to about 4,000 documents from nearly 400 petitions. By March, the project aims to put online every petition for freedom case in Washington, D.C., between 1800 and 1862 for scholars, teachers and the public.

Digitizing the petitions puts the individual experiences of slaves at the forefront, said William G. Thomas, UNL professor of history and the project’s principal investigator.

“We need to put enslaved individuals at the center and represent their life histories in ways that we’ve not yet been able to do and the digital environment allows us to attempt to do that, to represent individual experience in the larger context of a dehumanizing social system,” Thomas said.

Halfway through a two-year grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, Thomas and researchers from UNL’s Center for Digital Research in the Humanities and colleagues from the Maryland Institute for Technology in the Humanities have revealed previously invisible family networks and have given dimension to the everyday lives of slave families through their social ties.

“The family networks that we’re beginning to uncover are deep, extensive, are multi-generational and they move across race,” Thomas said. “Individual slave petitioners are connected into white and black families in D.C. in ways that we may not have realized. Now we can start to see those patterns.”

Until the project took flight, the only real record of these petitions was a bare-bones index of records in the National Archives and Records Administration, where the original documents are kept.

Thomas said that many more petitions of freedom have been found than were previously thought to exist. This is a boon to the project, he said – each petition “is capable of adding a new dimension to what we know about how these suits were brought, in the first place, who knew whom, and the social fabric of early Washington.

“When you look at the whole collection of these petitions for freedom, you can start to see the social world of enslaved families in the Washington D.C. area in a way that we otherwise couldn’t,” Thomas said. “You wouldn’t be able to put the whole family network together, if you were just looking at one case.”

Thomas said the family networks being uncovered would be useful to African American genealogists.

“This resource is going to be available to tap into and start to piece together some family history that they may not have been able to penetrate because of the inscrutability of these documents and because disentangling these names and relationships is extraordinarily difficult work,” he said.