After 25 years of designing and leading a variety of large-scale projects for a Kansas City firm, Karen Stelling joined the University of Nebraska–Lincoln engineering faculty in 2013.

It was a career pivot that brought her back to her alma mater, and where she has been able to pursue her passion of growing tomorrow’s leaders.

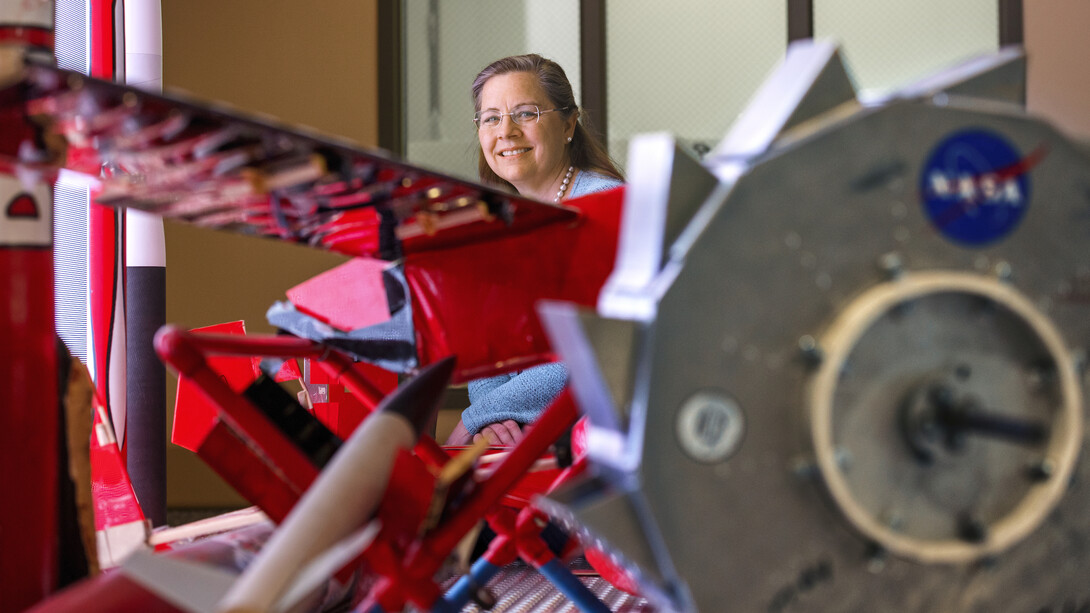

Stelling, a professor of practice in mechanical and materials engineering, has received teaching accolades, and most recently celebrated a huge achievement with the Aerospace Club she advises — the selection by NASA of the Big Red Sat-1 research satellite to be placed into space orbit. One of only 14 projects, it is the first in Nebraska to be selected. The Big Red Sat team features AXP team undergraduates mentoring Nebraska middle and high schools students.

Nebraska Today recently sat down with Stelling to ask her how she got into engineering, how she made her way to teaching after a long professional career, and what teaching leadership looks like.

How did you decide to go into engineering?

It was kind of funny. When I was in high school and going into college, I didn’t know what engineering was. I came here to UNL, and I started in business.

I missed the math and science. I had taken a couple semesters of calculus in high school, and a high school classmate was in my honors history class and was majoring in electrical engineering, but I didn’t really know what that was. I was oblivious.

They had industrial engineering, and I thought that was probably the good mix of math, science and business, so I switched to industrial engineering. I took a drafting class, and I enjoyed that three-dimensional work. I took chemistry, and the professor, after the first test, said, “well, what’s your major?” And I said, “industrial engineering,” and he said, “with this grade, you can do better than that.” And I thought, I liked the mechanical. If I got the mechanical degree, I could still go back to industrial, but if I got the industrial degree, I might not be able to go into mechanical.

I switched my major to mechanical engineering. And the ironic thing is, when I was in high school, I took the ASVAB — the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery — and I scored really high in mechanical aptitude. And I showed it to my friends and said, “well, that tells you this test isn’t very good. I don’t know anything mechanical.”

What was your career like prior to joining the faculty?

I was really fortunate. I went to a consulting engineering firm, and what I got to do changed every two or three years. I started out as an associate engineer, learning how to design mechanical systems for facilities — heating, ventilating, air conditioning, plumbing, fire protection. I really loved fire protection. Then I went out on a construction site for a year and a half.

My friend that I worked with who is a civil engineer, we were the first two females who were sent full-time on a construction site. It was in the Mojave Desert, at Edwards Air Force Base, and it was an airplane hangar for NASA. It was for their next generation aerospace plane, but it was also right where the space shuttle landed.

I came back and I got to take more of a lead in the design of mechanical systems. After an experience with a client, I got to start managing projects for them. They became my client. I was still doing some design.

I moved to full-time project management. I got promoted to vice president when the client outsourced their facility engineering to our company to improve performance. After four years, I went back to the home office and helped with running the division I was a part of, which was aviation and facilities.

On my return, a main focus was sustainability. I led the effort of getting the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) certifications and accreditations going for the company. We went from one accredited professional, to over 250, and over 20 buildings certified.

The other thing I worked a lot on was when there were projects where the client wasn’t happy — maybe we’re behind schedule, or it looked like we’d lose millions of dollars — I was told “here, Karen, make the client happy, try not to lose money and get done on time.”

The last big project that I managed was a convention center extension in Qatar. I managed the design side, where we had about 20 design subcontractors, our fee was over $36 million and the construction cost was over $500 million. It was the first LEED-certified building in Qatar and in fact, in the Mideast, and it was a state-of-the-art convention center.

What made you decide to transition to teaching?

I felt like I wanted to do something where it felt like I was giving back more. I had been thinking for a few years about how I might be able to give back and actually talked with the engineering dean down at University of Missouri–Kansas City, who was a friend, and he suggested education, and I thought that would probably be a good fit. I actually asked the engineering dean here at the time for a letter of recommendation, and instead he offered me a job. He wanted somebody to teach leadership to engineering students, and to help them develop professional skills. When he said that, it just really resonated. And it’s something I’m passionate about — bringing more great leaders out into the community.

What is your favorite thing about teaching?

My favorite thing about teaching is when I can help students grow, and when you can see that development. Because I’m teaching professionalism, to see that maturing and that bigger worldview and that openness to growth occur, that’s what’s most satisfying to me. I want to be a resource for them, so when they are engaged, and we share perspectives and ideas that help us grow, that’s the most exciting thing.

You helped develop a leadership curriculum for the College of Engineering. What does that look like?

We have an Engineering 100 class where the students learn about the interpersonal skills and about leading themselves. It’s an intentional sequence into Engineering 200, with professionalism and global perspectives. That’s where they work on teamwork, handling conflict and really understanding professionalism, respecting diverse clients and colleagues, and emotional intelligence. Then in 320 there are lessons on leadership, ethics and management. It’s getting to know yourself, then how you work on a team, followed by how do I become a good leader? The best leaders know how to be good team members and they know themselves.

You’re the adviser of the Aerospace Club, which has recently had some successes. What’s the importance for students to join organizations like the Aerospace Club?

Gallup did a poll, and I share this in my Engineering 200 class, but what they said is, success is less about the college you go to, and more about the experiences that you take from it. Part of it is having a faculty member who’s interested in you or that you connect with, and part of it is doing a project. It’s best if that project is over a year long, and you’re getting that hands-on experience. The Aerospace Club provides that hands-on experience, and they’re getting to work with other people, learning how to do things they never thought they could do. A lot of them get internships with NASA. Even though we don’t have an aerospace engineering degree, what they’re learning is so relevant, and they’re immersed in it. Their ability to demonstrate what they learned opens up all kinds of career paths and internship opportunities for them.