For some plants — like corn, Nebraska’s most widely grown crop — below-zero temperatures trigger a cascade of lethal damage. Freezing conditions cause formation of ice crystals within the plant, leading to cell dehydration and irreversible membrane damage.

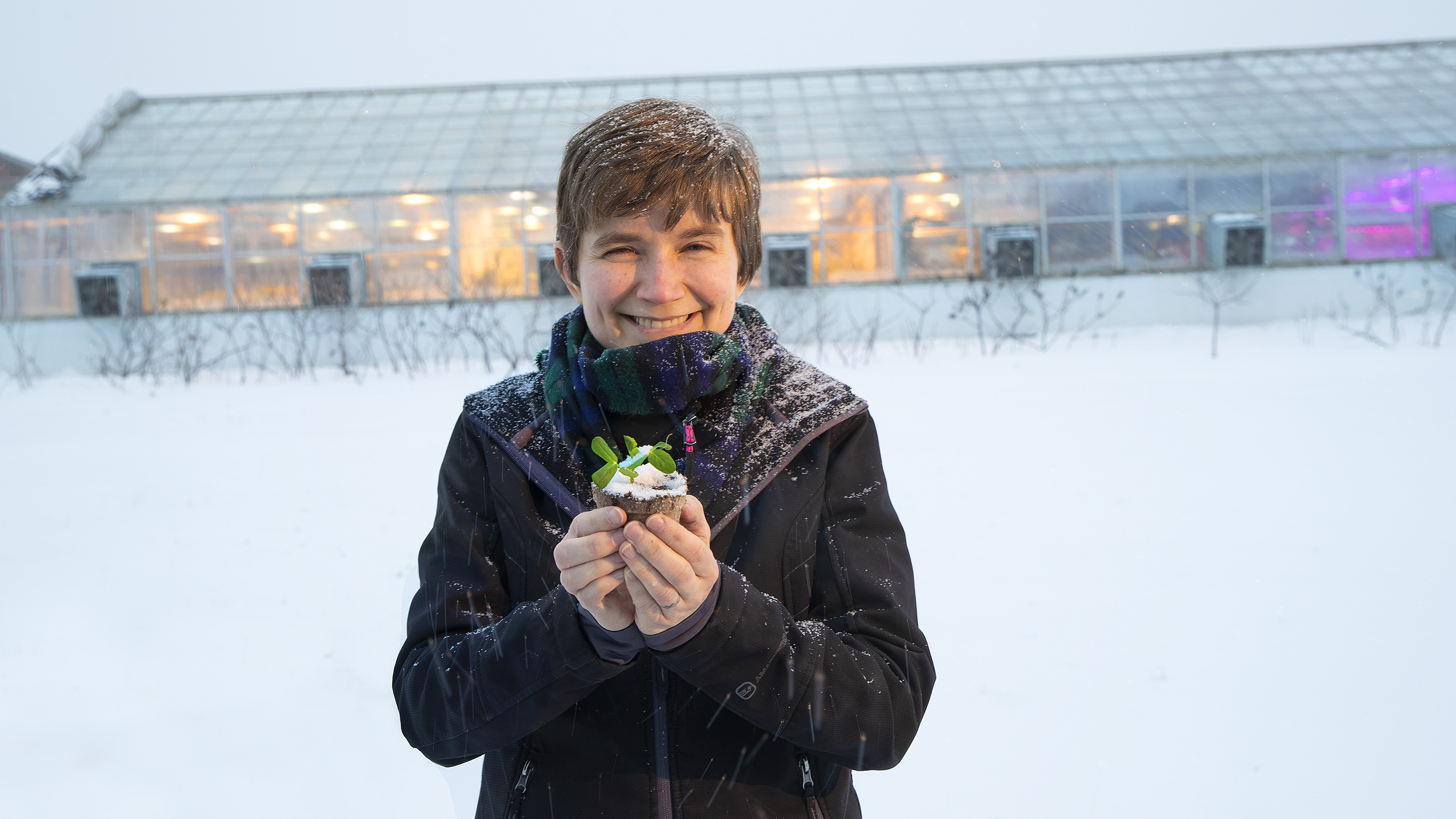

But for others, such as the flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana, the damage isn’t permanent — and the plant can bounce back from the cold. University of Nebraska–Lincoln biochemist Rebecca Roston is working to identify the properties and pathways underlying Arabidopsis’ ability to thwart ice-cold temperatures, with the long-term goal of enabling scientists to engineer freeze-tolerant crops.

She earned a five-year, nearly $850,000 Faculty Early Career Development Program award from the National Science Foundation to advance this work.

Developing cold-hardy crops would boost global food security for a rapidly expanding population, which is expected to grow from 7.5 billion today to more than 9.6 billion by 2050. This rapid growth demands increased yields despite climate change-fueled weather instability. One solution is crops engineered to survive at below-zero temperatures, which would lengthen the growing season and allow production in colder climates.

But currently, scientists don’t know the exact mechanisms enabling freezing tolerance, leaving them unable to replicate the key pathways in engineered plants.

“When you want to engineer for tolerance, you have to know what to engineer,” said Roston, assistant professor of biochemistry. “That’s why we’re studying how the chloroplast membranes in Arabidopsis functionally respond to the cold, and how these changes confer tolerance.”

Roston’s previous research identified a protein called Sensitive to Freezing 2, or SFR2, as a key player in stymying cold-induced cellular damage. But exactly what activates SFR2 remains unclear. Though Roston’s group uncovered an association between rising cellular acidity and SFR2 activation, they don’t believe the former directly triggers the latter. Nor does cold weather directly influence the protein.

“We know there is some additional signal involved,” said Roston, a member of the university’s Center for Plant Science Innovation. “The cold triggers this signal, and the signal affects the SFR2 enzyme, and then it does its work.”

She theorizes that the mystery signal is a kinase, an enzyme that fuels a process known as phosphorylation. During this process, a protein gains a phosphate group, an alteration that triggers certain functions. For SFR2, phosphorylation may trigger a protective response to freezing temperatures.

Precisely mapping out the domino chain — from freezing temperatures to kinase activation to SFR2 action — is important because it provides critical information to scientists trying to engineer freeze-resilient plants using SFR2, Roston said.

“Right now, we have a general idea of the pathway that exists in response to cold. But we don’t know which part to ‘push’ to make plants different,” she said. “If we ‘push’ the wrong part, it’s not going to be effective.”

Roston is also investigating how SFR2 confers protection. She knows that the protein, once activated, remodels the plant’s chloroplast membranes by causing the depletion, removal or accumulation of certain types of lipids. Now, she’s working to pinpoint how these changes stabilize membranes at freezing temperatures.

For the project’s education component, Roston is establishing a partnership between the Department of Biochemistry and the Nebraska Alumni Association, connecting undergraduate students to alums with relevant careers. She’s also launching the Plant Science Research Association, a group for postdoctoral and student researchers focused on science communication.

Additionally, Roston is producing a full-length graphic novel to help the public better understand genetic engineering in crops. With the help of a professional author and artists, she’ll create a piece to distribute across various venues, including an undergraduate biology course, a Nebraska State Fair exhibit and the university’s annual Women in Science conference.

NSF CAREER awards support pre-tenure faculty who exemplify the role of teacher-scholars through outstanding research, excellent education and the integration of education and research.