· 4 min read

Inside the ‘mechanical stomachs’ reducing campus food waste

Before last year, food thrown away at Nebraska’s Selleck and Cather dining halls followed a complex path.

First, into garbage bags, which were taken away by custodial staff; then, onto a truck, which produced greenhouse gases as it transported them away. Eventually, the food made its way to a landfill, where it continued to emit more carbon into the atmosphere as it decayed.

Today, thanks to two new campus devices known as biodigesters, that process has become much simpler and a whole lot more sustainable.

“What a biodigester does is take solid foods that get thrown away and mixes them up into a nutrient-rich liquid that goes down the drain,” said Dave Annis, director of University Dining Services. “The simplest way to describe it is that it’s a mechanical stomach, always digesting away.”

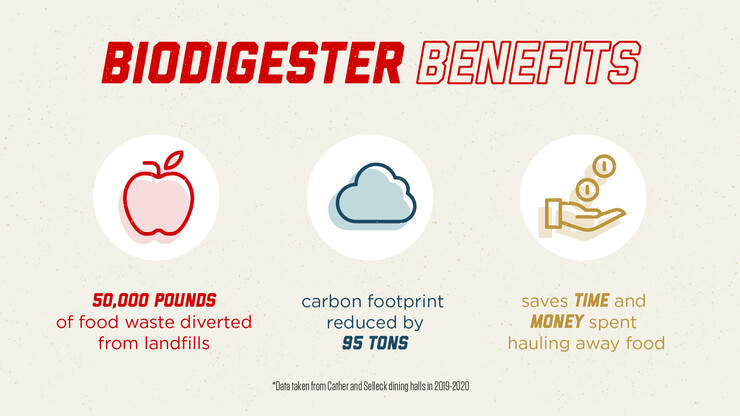

Selleck’s biodigester was installed in October 2019. Cather’s was installed this past June. Combined, the devices have diverted over 50,000 pounds of food waste from landfills and reduced Nebraska’s carbon footprint by 95 tons.

“For our sustainability goals, it just makes sense. We don’t have the ability to have a big compost pile anywhere close, and composting involves a lot of labor, so this seems to be the next best thing,” Annis said.

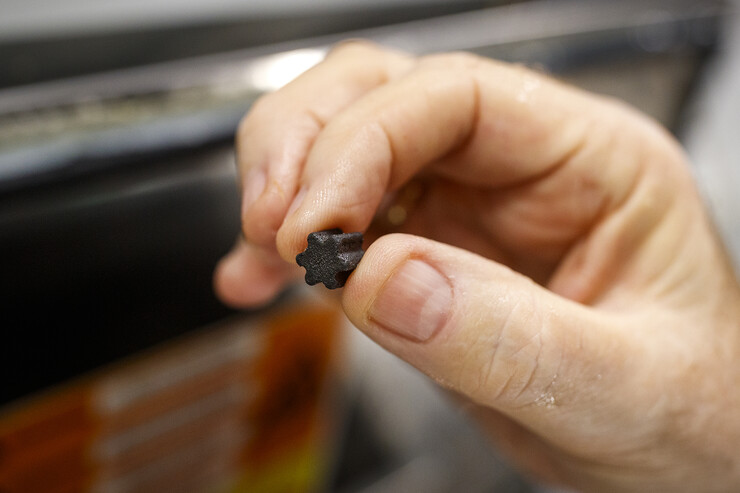

Each biodigester, which can process up to 400 pounds of food a day, resembles a large, metal box. Inside is a tank filled with small black pellets and a paddle that automatically turns to mix in the digesting ingredients and food.

“The first thing we do is introduce a safe, food-grade enzyme to the tank. We let that sit for a few hours to get it started. It’s like using yeast when you’re baking,” Annis said. “Then, you feed it a little bit of starter. We mix five pounds of rice, five pounds of sugar and a little bit of water together. After it’s been digesting that for about six hours, you can just start putting food in.

“It can digest just about anything. It’s pretty amazing to see a half-eaten hotdog go in there and be gone by the next day.”

The biodigesters not only help the environment, but also save the university time and money.

“The people that were the happiest about it were our facilities people — the people that had to come in a couple times a day and haul away all the big, messy, heavy bags of garbage,” Annis said. “There’s none of that now. After we put the one in Selleck, they were the ones that came to us and said, ‘Well, when are you going to put in the next one? We really like these things.’”

Unlike other sustainable food waste disposal methods, such as composting, the liquid produced by the biodigesters isn’t currently being cycled back into the environment. However, Annis said he aims to change that in the future.

“There are places that collect that and use it for fertilizer, but we aren’t ready for that yet,” Annis said. “It’s one of those aspirational goals to be able to find a use for what comes out and goes down the drain now and use it for other purposes — sort of closing the circle.”

Having seen the benefits of the biodigesters firsthand, Annis also wants to eventually put one in every dining center on campus.

“We still have three dining centers that don’t have them,” he said. “We had hoped that we’d have a couple more in over the summer, but COVID sort of changed everyone’s plans, and we just didn’t have the resources at that point to be able to do that. But it’s still on the back burner, and we’ll get to them as soon as we can.”