A University of Nebraska-Lincoln computer scientist is harnessing the power of artificial intelligence to help undergraduate STEM students improve their academic performance. His project will strengthen the pipeline of college graduates prepared for STEM jobs, the number of which in the United States is expected to expand by about 10% by 2030.

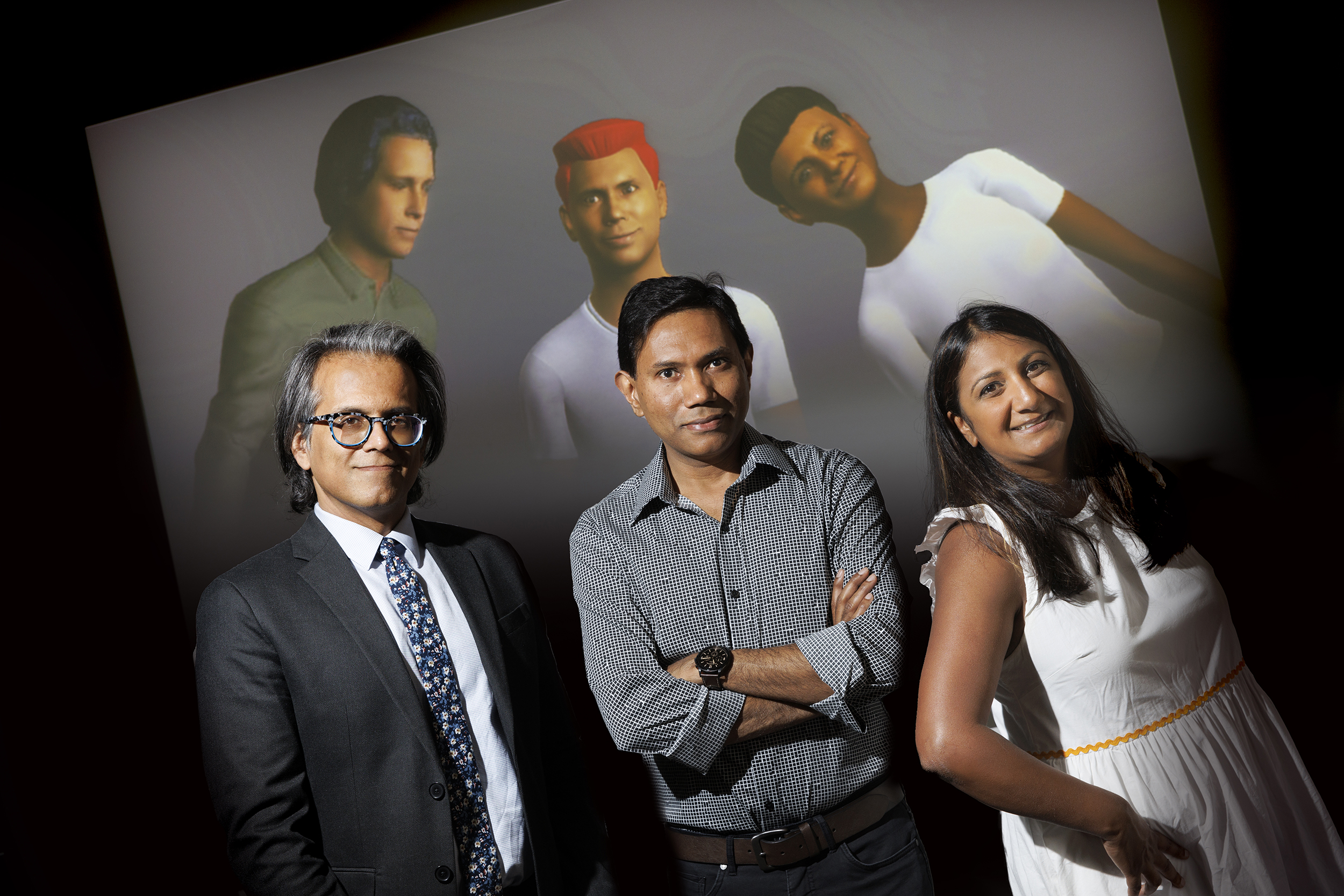

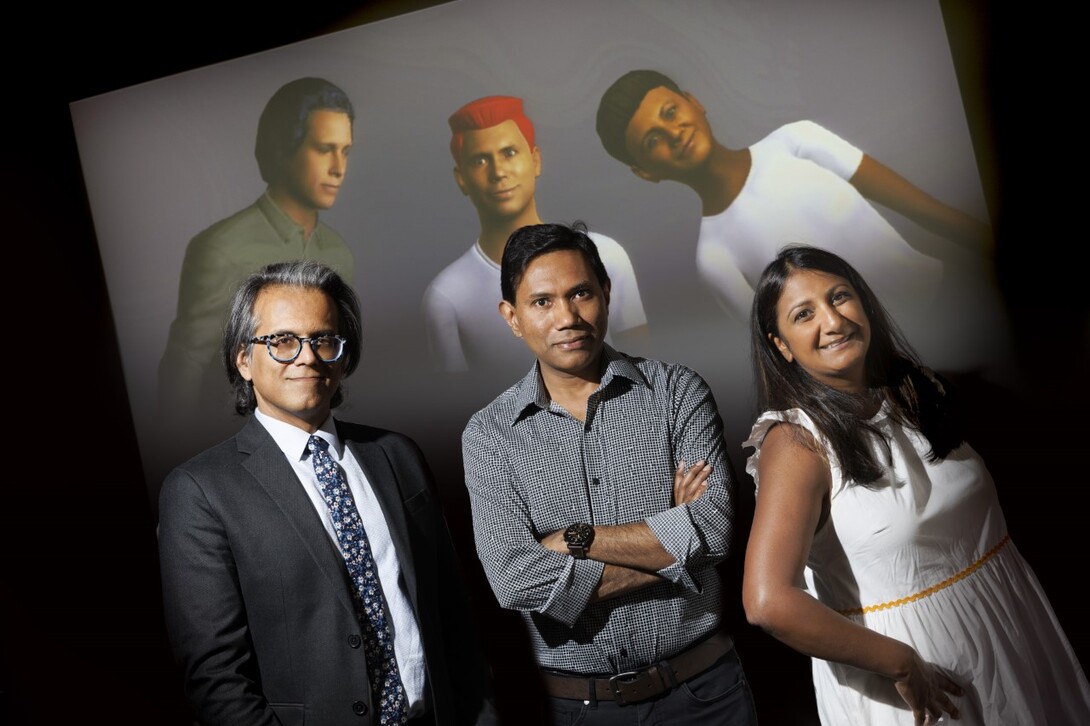

With a three-year, $600,000 grant from the National Science Foundation, Mohammad Hasan is developing a machine-learning-based app, called Messages from a Future You, aimed at providing students with targeted, real-time interventions that boost their performance in STEM courses. Using the app, students can engage in dialogue with their “future self” — an avatar derived from the student’s photograph — about how to boost their grade.

The app would be the first that uses an artificial agent to provide tailored interventions that account for the myriad factors impacting a student’s final grade.

“The existing approaches mainly target academic improvement based on just academic performance alone,” said Hasan, assistant professor of big data and artificial intelligence in the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering. “But end-of-semester performance is not just influenced by academic activities during the semester. It is shaped by other things: family background, socioeconomic status, peer interactions, interactions with the instructor, science identity and more.”

The app would be a cost-effective, portable tool to combat a national attrition rate from STEM majors that hovers around 50%, driven largely by students’ poor academic performance. From his seven years of experience teaching large introductory courses at Nebraska, Hasan had first-hand knowledge of why undergraduates may struggle early on in a STEM major.

“Helping students in large classes is not easy, because you can’t really talk to every person throughout the semester, and students would not come to you unless they are in real trouble,” he said. “And usually when they come, it’s at the very end of the semester, when it’s not really possible to meaningfully help them.”

Hasan started brainstorming ways he could boost student performance. Although institutional-level change may hold the most power to move the needle, Hasan believed there were smaller-scale, less expensive ways to help students.

He recognized the power of machine learning to power an app that would help students succeed: The app could “learn” about the student’s behavior and background, then use that data to predict future performance and provide advice for changing that trajectory.

Through the app, students reluctant to approach an instructor for help — those who are introverted or feel intimidated, for example — would have a pathway for accessing personalized assistance.

“It’s just like a proxy of me,” he said. The proxy would take shape on-screen as a student’s doppelganger from the future, which Hasan felt would resonate more strongly than simple text messages.

To build a pilot app, he collected academic performance data from about 300 Husker undergraduates in a computer science course and built a grade forecasting app. He launched the pilot in a sophomore-level class.

The app increased the number of students who passed. But the results showed that despite being on a similar academic trajectory at a certain point in time and receiving the same messages from the app at those junctures, students’ final grades were not the same.

The NSF project is aimed at pinpointing the factors driving these varying outcomes. Hasan’s hunch is that the one-dimensional nature of the pilot tool — its basis in academic data alone — painted an incomplete picture of a student’s story, missing key factors that would explain the different outcomes.

To fill that gap, he teamed up with project co-investigator and former Husker researcher Bilal Khan, developer of the Open Dynamic Interaction Network. Using the ODIN software platform, they are collecting nine dimensions of academic, social and psychological data to train the model.

Hasan will then use a machine learning technique called clustering — the automatic grouping of data — to organize the students’ trajectories into distinct “story types.”

Identifying these story types is the linchpin of the project: By “knowing” which grouping a certain student belongs to, the app will provide the right messages and advice.

“If a student belongs to story type A, we will understand that the student falls into a particular behavioral pattern,” Hasan said. “By knowing that pattern, we can provide more targeted intervention to the student.”

Co-investigator Neeta Kantamneni, associate professor and director of the university’s Counseling Psychology program, is leading efforts to develop the interventions. Her team will craft messages to deploy to students at certain points in time, depending on how their story is unfolding.

The interventions will mirror the type of advice provided in face-to-face counseling. Students might be encouraged to engage in mindfulness activities to reduce stress or worry, collaborate with peers to enhance a sense of community or seek extra help during office hours.

A major benefit is that the interventions will come to students in real time, providing them with help when they need it the most. This is an advantage over in-person counseling, which often happens after students become dissatisfied with their major.

The app would also bolster students’ access to help during a time of long waitlists for in-person counseling, both at the university and nationally. Kantamneni is optimistic that virtually delivered interventions could help bridge that gap.

“We don’t want people to leave a whole career domain simply because they had one difficult class,” said Kantamneni. “That’s what we see sometimes. And my goal is that that doesn’t happen, particularly for students who are underrepresented in these classes — so women, students of color, first-gen students.”

The app’s design has potential beyond the field of STEM education, Hasan said. Allowing people to “see” how today’s behavior influences tomorrow could be especially salient in public health. Seeing one’s future self as sick could be a powerful nudge to follow medical recommendations like wearing a mask, exercising or getting more sleep.

Hasan also hopes the app will shine a light on the positive potential of intelligent machines.

“I know that these days, people are very apprehensive about the role of AI,” he said. “But by using AI for social good, we can show that there is this other side of AI, which is not for making money or for just doing business. We can use AI to improve the life of the students. Within the university, this is a very useful addition to improve the quality of education.”