The physical characteristics of a plant can reveal a lot about its underlying genetics. How many kernels of wheat does a single plant produce? How quickly does a corn plant grow? How much water does it use? Understanding a plant’s physical traits, and linking those traits to specific genes, ultimately drives development of improved crops, higher yields for farmers and greater food security worldwide.

The science of capturing the characteristics of plants is called phenotyping, and until recently, it has been extremely time- and labor-intensive. Historically, trained researchers relied largely on the sight, touch and feel of a plant to record and understand the phenotype. Nowadays, technologies such as drones, robots, cameras and laser scanners can measure far greater numbers of plants instantly.

Plant phenotypes vary from region to region, in large part because plants are good at adapting to environmental variables, such as rainfall and soil composition. However, this variation can also be attributed, in part, to inconsistent protocols, technologies or algorithms used by researchers, said Yufeng Ge, an associate professor in the University of Nebraska–Lincoln’s Department of Biological Systems Engineering. Plant phenotyping efforts, although rapidly burgeoning, are still localized and isolated. This creates a series of problems, including difficulty in comparing and interpreting results, underused research data and unknowingly duplicated activities, Ge said.

With the help of a new $3 million grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Ge is leading a team of researchers from three universities who are working to change that.

The grant will bring together researchers from Nebraska, Texas A&M University and Mississippi State University to continue to expand phenotyping research already in progress; to expand the use of drone-based and other high-tech phenotyping methods; to create nationwide standards for collecting, cataloguing and analyzing phenotyping data; to teach the next generation of plant scientists how to organize, understand and effectively use the massive amount of information that high-tech phenotyping practices produce; and to make connections between a plant’s physical and genetic properties.

“Ultimately, we’re trying to accelerate the discovery of genes and gene networks in plants that have significance in the production of food, feed, fiber and fuel,” Ge said.

At Nebraska, Ge and other researchers have been using drones and other technology to develop and refine new ways of phenotyping since 2014. In a greenhouse on Nebraska Innovation Campus, plants move along a conveyer belt into different chambers, where they’re photographed by cameras that can identify traits beyond those that can be seen by the naked eye — for example, nitrogen content and leaf temperature. At the Eastern Nebraska Research and Extension Center near Mead, a Spidercam on cables moves over a test field, capturing images of plants as they grow and, just as at the Innovation Campus greenhouse, measuring both seen and unseen traits.

The images, measurements and other data that researchers are able to capture using these research methods are invaluable, Ge said, but the technology is cost-prohibitive for widespread use. The grant will allow engineers involved in the project to work toward the development of more affordable versions.

The project also calls for the creation of standards for the types of sensors used and information collected, which will allow researchers from across the United States to easily analyze phenotyping data captured anywhere.

Ge and others will also collaborate with the Genome to Fields Initiative, which brings together researchers from an array of organizations, including Iowa State University, the University of Wisconsin and the Iowa Corn Growers’ Association, to better understand the function of corn genes across different environments.

“The project paves the way for a nationwide, drone-based phenotyping network where tools and protocols are standardized, experiments are coordinated and efforts are concerted, and data can be seamlessly shared,” Ge said.

For the potential of a nationwide phenotyping network to be fully realized, Ge said there must also be a nationwide network of researchers equipped to work with the vast amounts of data such a network would produce. To meet that need, Ge and others involved in the project are creating a curriculum that teaches the next generation of plant scientists the tools they will need to understand and use the data successfully. Students will need to understand the sensors that collect the measurements, as well as the measurements and images themselves. They also will need to know how to use phenotyping data with other data sets — sequencing data, weather and precipitation data, soil data and more — that together can provide a clear picture of how genes and outside factors work together to determine a plant’s characteristics.

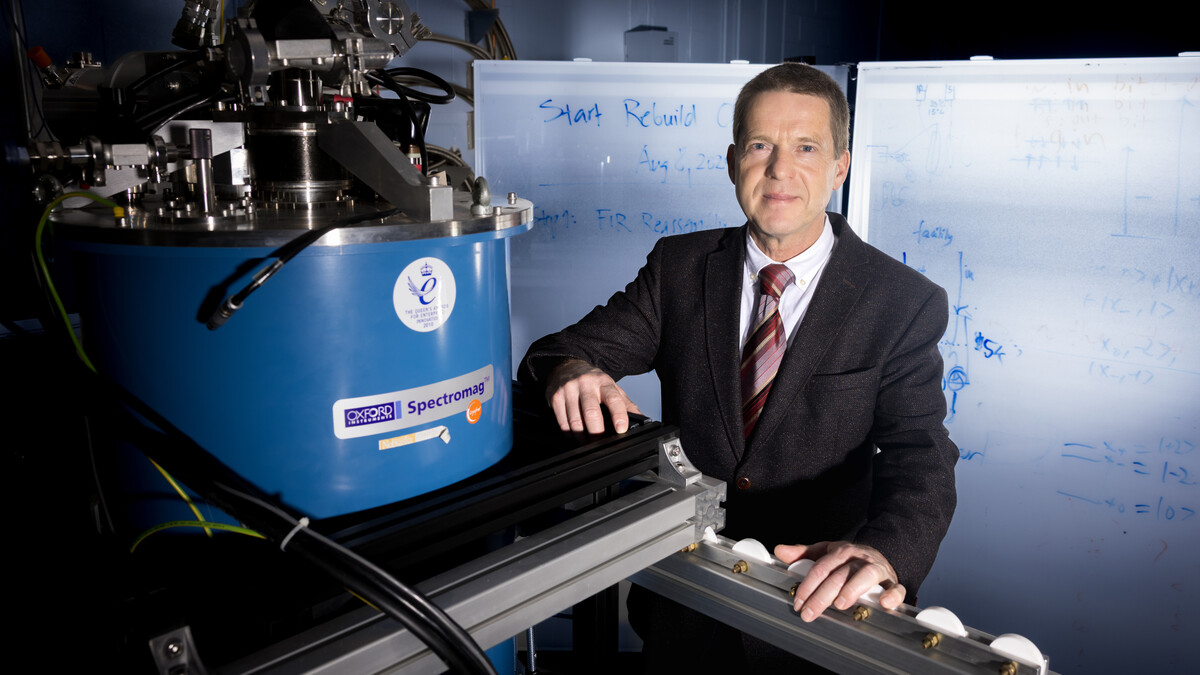

Archie Clutter, director of the Agricultural Research Division at Nebraska, said the award takes the university’s already renowned phenotyping program to the next level.

“This project has the potential to change the entire discipline of phenotyping, starting with the way data are collected all the way through the way that data are analyzed and shared,” Clutter said. “It’s an impressive, ambitious and very important project that could have a huge impact on how new crop lines are developed.”

Husker researchers involved in the project include Ge, James Schnable, Stephen Baenziger, Yeyin Shi, Leah Sandall, Vikas Belamkar and Frank Bai. The team at Texas A&M University is led by Seth Murray and Amir Ibrahim, and the team at Mississippi State University is led by Alex Thomasson.