You can find the fruits of his labor in movie theaters across America. Depending on the weekend, you might find the man himself in London or Bangkok.

He’s not a movie star on a worldwide press junket for his latest blockbuster. But Norm Krug has become a star in his field — especially when he’s planting or harvesting it.

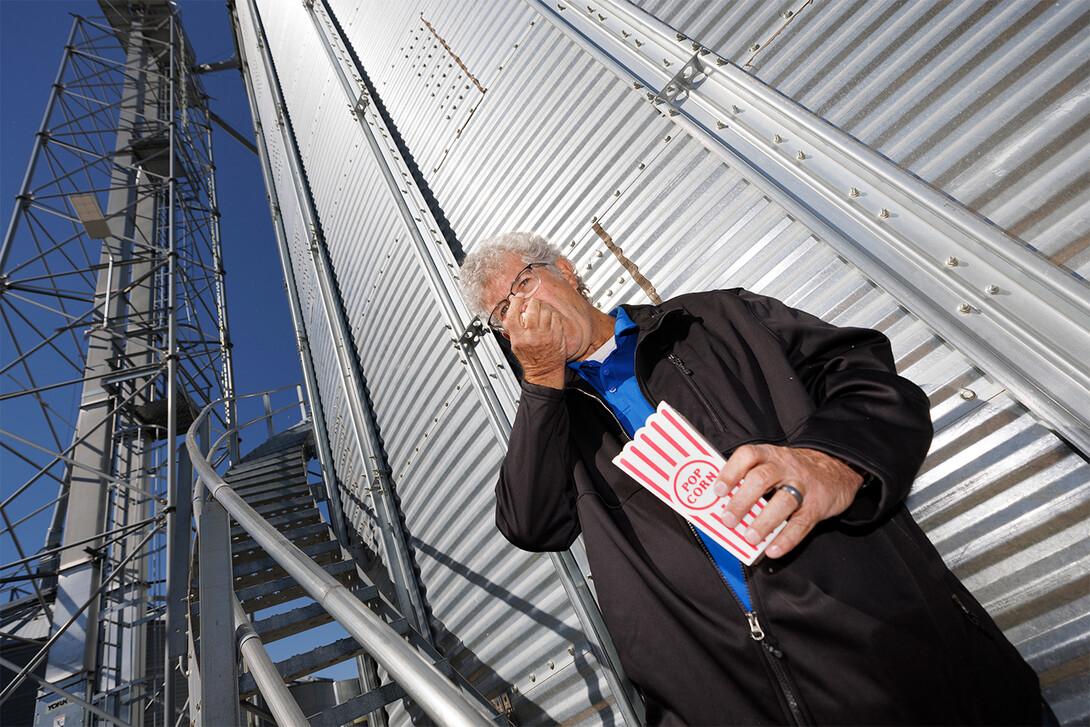

The Husker alumnus from Chapman, Nebraska, a village with fewer residents than an ear of corn has kernels, now presides over a global popcorn company whose product is grown in seven states and has sold in more than 70 countries.

“It’s become quite a large operation,” Krug said of his business, Preferred Popcorn. “We’re one of the larger popcorn companies in America, and probably the world, as far as that goes.”

In 1998, two decades after earning a bachelor’s in animal science from the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, Krug founded Preferred Popcorn with a few fellow farmers from the Chapman area. As the son of a “hardworking tenant farmer” who had grown popcorn for 45 years, Krug already had long experience with the crop. At the time, though, he just hoped the new company could supplement his income while giving local farmers another option for supplementing their dent corn and soybean.

Naturally, Krug began by reaching out to movie theaters, which were attracting droves to see the likes of “Titanic,” “Armageddon” and “Saving Private Ryan.” Yet he soon found himself feeling like the hapless businessmen sometimes depicted on the silver screen, cold-calling unreceptive clients who were more likely to hang up than listen up.

“When we started out, we had zero name recognition,” he said. “And when we would call the theaters, it was, ‘Sorry, we use Orville (Redenbacher’s),’ and click.”

Then he dialed up his alma mater’s signature theater: the Mary Riepma Ross Media Arts Center, better known to Huskers simply as The Ross.

“They gave us an equal playing field,” Krug said. “It was really an encouragement to get our popcorn sold at The Ross. They were one of the first that took a chance on us.”

In those early days, years before dozens of semis handled his domestic distribution, Krug would toss a bag of kernels in the bed of his pickup, make the 90-minute drive east to Lincoln, and drop his popcorn at The Ross before taking in a Husker game at Memorial Stadium. He was thrilled and thankful for the business. But he was still growing more popcorn than he knew what to do with: Just one 50-pound bag of kernels, after all, could produce a thousand 32-ounce servings of popcorn. So the amateur entrepreneur started attending trade shows with the aim of drumming up more customers. The devout Christian’s first stop? Sin City.

“Here are these farmers going to Las Vegas. All we had was a sack of popcorn and our emblem, and there are all these large, amazing booths,” he recounted. “I’m sure we were the smallest popcorn plant in the world at that point. But we did have a good knowledge of popcorn and how to produce it.

“I think it’s a good story of: Stay with it. Don’t be discouraged. Have a mission. Do your job, and do it well.”

As it turned out, his company shared a trait with the crop it was selling: Once it gained some steam, it expanded in a hurry. That Vegas road trip yielded a sale to buyers in Jakarta, the capital of Indonesia. Krug followed it with a visit to Thailand, where the fish-out-of-water managed to hook more clients. All the while, he was finding friends in people he never anticipated meeting and common ground in places he never expected to set foot.

Once, during a stop in China, he spoke to a farmer with the aid of a translator. Krug was curious about what improvements the farmer wanted to see in his crops. His answers were familiar: varieties that stood straighter, were easier to harvest and ultimately sold for higher prices. For Krug, the conversation helped hammer home that farming, like music or math, is something of a universal language.

“Farmers want the same things halfway around the world,” Krug said. “I was as far from Nebraska as I could get. We want exactly the same thing.”

Business had picked up back home, too. Whereas movie theaters had once refused to even give Preferred Popcorn a try, the company was now supplying its product to Marcus Theatres and every other cinema in Lincoln. Today, Krug said, much of the popcorn sold in U.S. theaters is Preferred.

Though experience and name recognition have helped the business grow, Krug likes to think that Preferred Popcorn’s attention to detail and commitment to quality have also played their parts. The company keeps track of which growers have contributed which popcorn, awarding bonuses to those whose kernels have sustained minimal damage — an effort to ensure that the maximum percentage of kernels will actually pop. And each of the 65 bins at the Chapman-based headquarters is equipped with a sensor that monitors temperature and moisture, both of which can potentially take the pop out of popcorn.

Krug is proud, too, that Preferred Popcorn’s growers — about 50 of whom farm Nebraska’s land — have adopted crop rotations that reduce reliance on pesticides and no-till practices that curb erosion of topsoil. On one especially blustery mid-October day that marked the end of his annual popcorn harvest, with winds gusting to more than 40 miles per hour, Krug pointed out the lack of dust blowing from his fields.

“You have to have practical solutions, and the university has always been great at that,” said Krug, who dedicates about a thousand of his own acres to popcorn. “I do attribute a lot to my university background.

“People tend to think environmentalists and farmers are on different sides. We’re not. Who wants to preserve the soil more than I do? I have 16 grandchildren.”

As Preferred Popcorn nears its 25th anniversary, Krug continues to eye new opportunities. The company recently began popping its own popcorn for the first time, developing a ready-to-eat product line based out of Waco, Nebraska — a village even smaller than Chapman.

“We hope that grows into a large establishment,” he said, “and employs more people in another small Nebraska town.”

For a frequent flier who’s become attuned to the cultural customs of Japan and France and Egypt, Krug makes no secret of the fact that his Nebraska roots still run as deep as those anchoring the popcorn plants surrounding his native Chapman. Earlier this year, he embarked on a trade mission to the United Kingdom and Ireland — affording him the chance, coincidentally enough, to watch his beloved Huskers kick off their season in Dublin.

“I’ve been able to travel to a lot of places in the world, meet a lot of incredible people, but I’m always glad to come home,” Krug said. “Nebraska is a great place to live, and I’m thankful for it.”