As she turned the marked-up pages stored in the University of Nebraska–Lincoln’s Archives and Special Collections, Melissa Homestead pointed out the differences in handwritten edits on a manuscript of Willa Cather’s short story, “Two Friends.”

Those notations and the editing were done by two people: Willa Cather, the author, and Edith Lewis, her life partner of 38 years.

“In this second, later typescript, which was professionally typed by Willa Cather’s secretary, you can see this one is almost all Edith Lewis editing it, and she’s really working over this initial paragraph, which is about memory and this metaphor of birds and tides,” Homestead said, adding that most of the edits were made when Cather and Lewis visited their cottage on Canada’s Grand Manan Island in 1931.

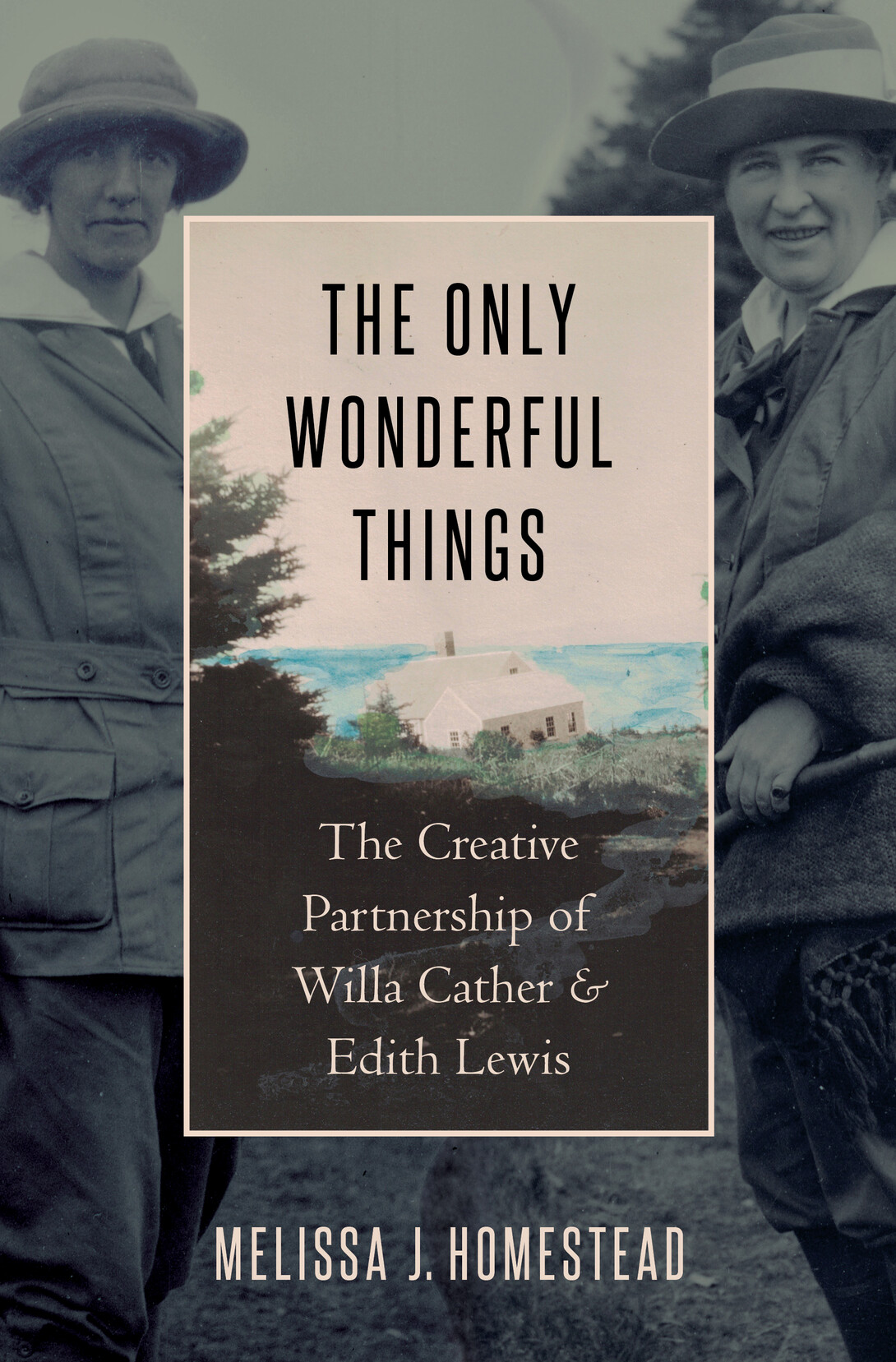

The markings found in scores of documents that Homestead has studied help tell a story that’s been sidelined by Cather fans and scholars, but is now being told in Homestead’s new book, “The Only Wonderful Things: The Creative Partnership of Willa Cather and Edith Lewis,” published April 1 by the Oxford University Press. Through meticulous research on the surviving manuscripts, letters and other personal documents held in Nebraska’s collections and elsewhere, Homestead has been able to fully credit Lewis as a frequent collaborator on Cather’s works and reconstruct their lives as domestic partners.

“I spent about the first 13 or 14 years saying that I was not writing biography, and then I realized I was — not writing biography in the traditional sense — but in the end, I did write biography,” said Homestead, professor of English and director of the Cather Project. “I started from the idea that it was both a true life partnership and that Lewis was Cather’s editorial collaborator in producing her fiction. (The relationship) had been often mischaracterized, but I started with the conclusion that there was a ‘there’ there. As I spent more and more time in archives, evidence emerged that demonstrated that I was really right from the start.”

From fan to scholar

Homestead joked about the process of researching and writing the book taking 18 years — and finally having a teenager ready to leave the nest. But she has been fascinated by Cather and Lewis for much longer.

She recalled first becoming a fan of Cather’s fiction as a high school student in Pennsylvania, when she prepared a college admissions essay regarding early 20th century literature. Her English teacher, Judith Reese, recommended two authors to her: Cather and Edith Wharton.

“I ignored the Edith Wharton suggestion and went to the library and checked out ‘O, Pioneers!’ and ‘My Antonia,’ and stayed up the whole weekend reading them, and I was totally hooked, so I have been a Cather fan since then,” she said.

“It seemed to be a roadblock,” Homestead said. “At the time, I didn’t really know anything about how to do research in archives, and this card — which I slightly but significantly misremembered — seemed to say this relationship was hidden.”

Working in a rare book and manuscript library, then as a paralegal, and eventually earning her doctorate considerably sharpened those archival research skills. Also aiding the quest? Joining the English faculty at Nebraska in 2005.

Rare finds

Homestead traversed through many places in search of original documents, but no other archives were as substantial as those in the Special Collections and Archives at Love Library.

“We have, by far, the best collection of Willa Cather-related materials of any library in the world,” Homestead said. “We have more Cather letters than any other library. We have more of the working drafts of her fiction with both Willa Cather and Edith Lewis editing them. I spent so much time in the Special Collections reading room here looking at those materials, which are really just extraordinary.”

In a way, the university’s Cather collection prolonged Homestead’s research for the book. Many times, when Homestead thought she’d reached the end of materials available to her, the estate of Willa Cather’s nephew, Charles Cather, would add materials to the Charles Cather Collection, first donated in 2011. Other materials were purchased by and donated to the library. When the Charles Cather Collection first arrived, Homestead was delighted to find that it included many of Lewis’s personal papers, including many letters to her, along with records of her travels with Cather. Most notable were their visits to the Southwest, which served as fact-finding trips for “The Professor’s House” and “Death Comes to the Archbishop.”

In one such notebook, Lewis drew maps of the places they visited and the excavated Mesa Verde pottery that features in “The Professor’s House.”

“When the collection first came, there was this record book, and the fact that it existed was really sort of extraordinary,” Homestead said. “There are still so many things we haven’t figured out about this trip, but there are things in it that are just wonderful. There is a map that Edith Lewis drew of the area around Española Valley, and there are sketches of the Mesa Verde pottery, and there are also notes in Cather’s hand where she’s clearly thinking about writing what became ‘The Professor’s House.’”

It was finds like these that allowed Homestead to reconstruct the life Cather and Lewis led together. Homestead also visited many of the same places as she traced their lives.

In her own hand

Cather’s own letters, which are being digitized, annotated and archived by a team at Nebraska, also helped fill in some of the texture of their lives together, including special friendships and close relationships with family. Homestead said there is a myth that Cather and Lewis led very private, isolated lives. The exact opposite was true, she said.

“I think a lot of people have the idea that Cather lived in isolation practically everywhere,” Homestead said, adding that Lewis’s and Cather’s families knew each other, and that they shared many friends. “They had a community in Grand Manan Island who all vacationed together. You can also see the ways they were integrated into each other’s families. They spent time together.”

One letter in particular, from Cather to Lewis, gave Homestead the title for her book.

“The title comes from the one full dress letter from Willa Cather to Edith Lewis currently known to exist,” Homestead said. “I’m not convinced that all of their correspondence was destroyed or that they destroyed it, but this is what we have. It’s a beautiful letter that Willa Cather wrote in 1936.

“There’s the conjunction of Venus and Jupiter in the sky, and she describes it in this lovely way. And then she says … that if this is all just temperatures and science stuff, then we are the only wonderful things, because we can wonder.”

Putting speculation to rest

Scholars have disagreed on, or tried to bury, Lewis’s centrality in Cather’s life. In the book, Homestead explains some of the events that precipitated the erasure of Lewis, including the Lavender Scare, which connected homosexuality with communism after World War II, and the persecution of those suspected of being gay.

But most of all, Homestead endeavored to show how Cather and Lewis lived fulfilling lives, with their respective careers, friendships and family, and travels.

“I don’t think that Cather would have appreciated the ways that Edith Lewis has been denigrated and mocked,” Homestead said. “She chose to live her life for 38-and-a-half years with Edith Lewis. Let’s assume that there was something that she admired and respected in Edith Lewis. I think she would want that admiration and respect for her.

“I think they had a good life together, and I think the way they lived their life allowed them to nurture their own separate ambitions, as well.”