A chemical compound typically cast as a supporting actor in corn’s defense against a tiny pest might instead take a leading role, says a research-based rewrite from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

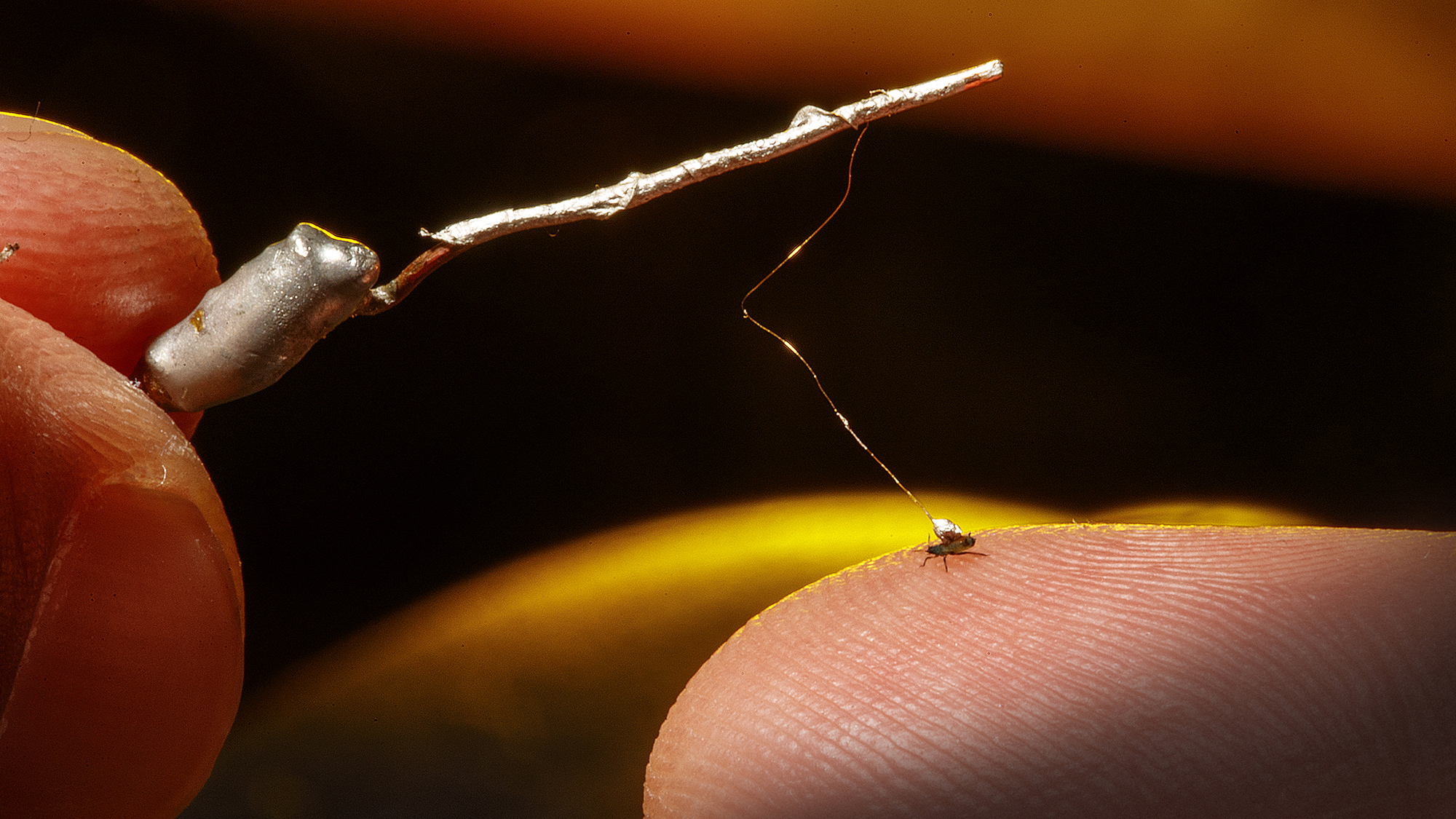

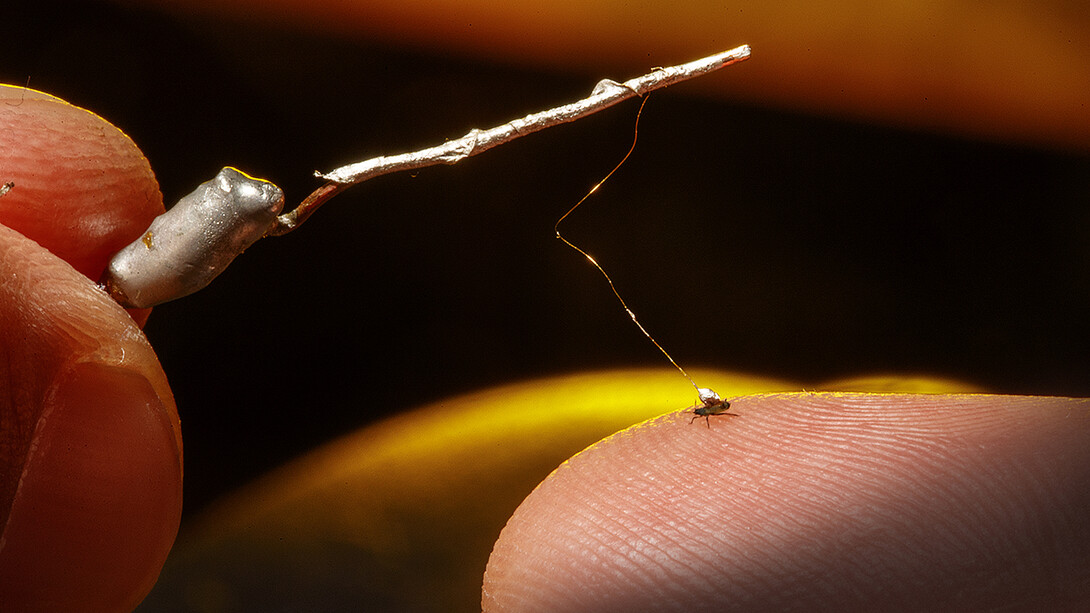

The Nebraska study showed that spraying a corn plant with one of its own compounds — 12-oxo-phytodienoic acid, or OPDA — can help deter the virus-carrying, pollination-disrupting insect known as the corn-leaf aphid.

OPDA has long been recognized as vital for synthesizing jasmonic acid, a defensive hormone deployed in response to aphids puncturing stalks and sucking corn sap through their syringe-like mouthpieces. That puncturing also kick-starts production of benzoxazinoids: compounds believed important in forming callose, a carbohydrate-laden layer that heals wounds and blocks access to sugar-transporting tissue.

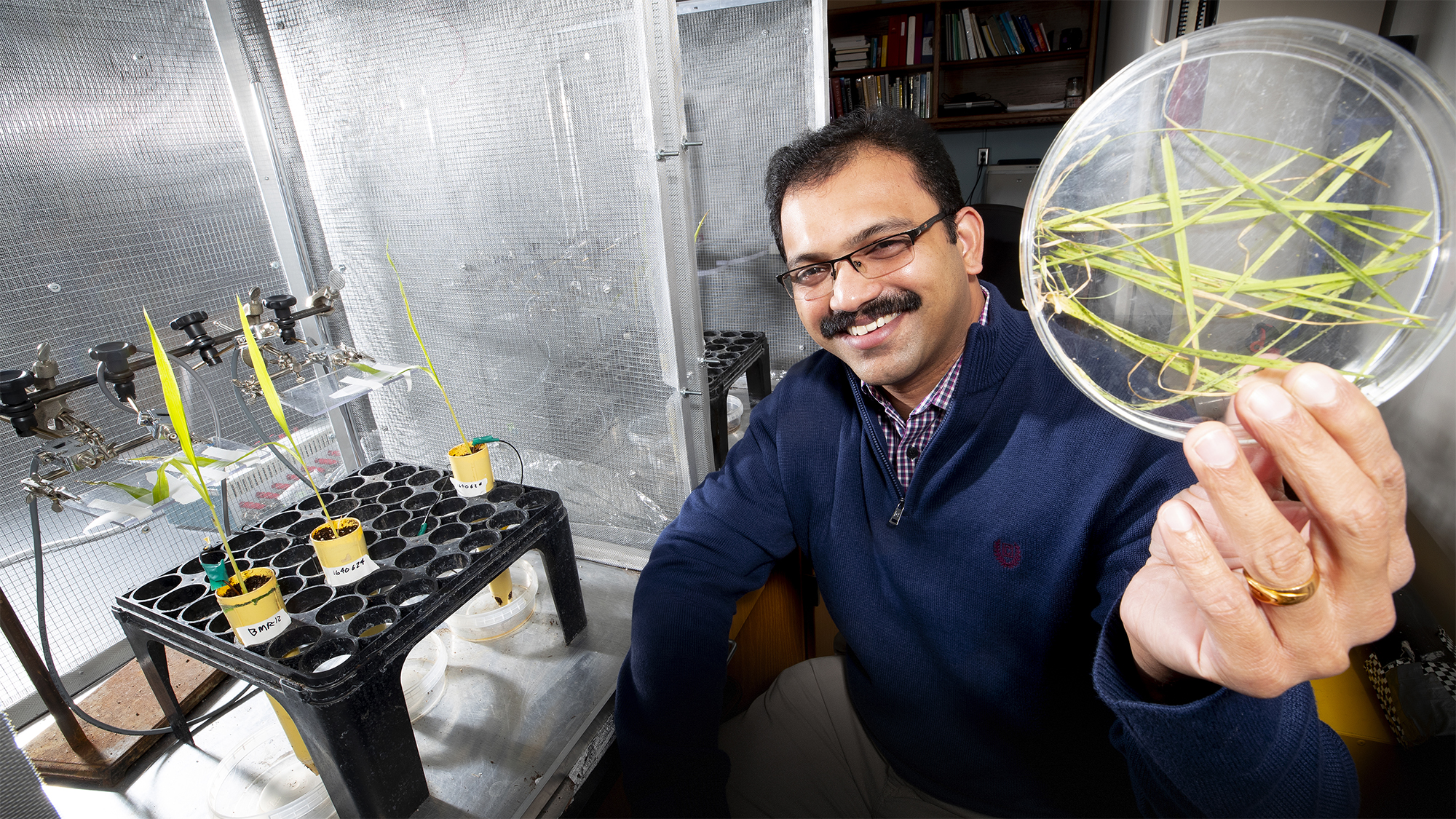

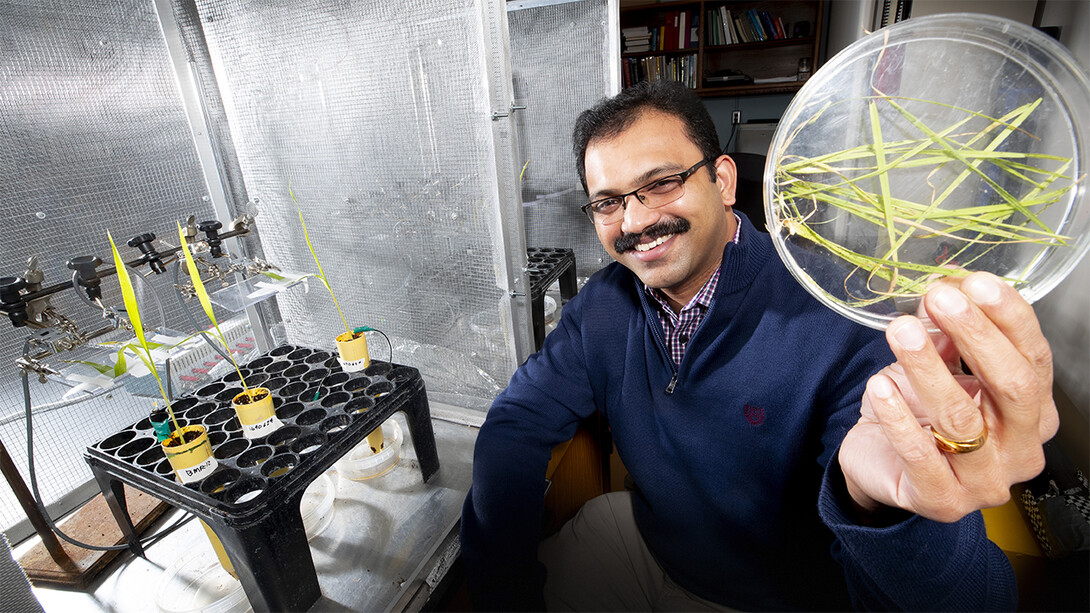

But experiments from Nebraska’s Joe Louis and colleagues suggest that OPDA alone, minus the aid of the plant’s two more famous safeguards, can protect against the pinhead-sized insect by triggering a buildup of callose. That knowledge could eventually help corn raise its carbohydrate shield before rather than after aphids attack, Louis said.

Based on recent feedback from the fields, stronger defenses could prove important going forward.

“In the last few years, our entomology extension folks are getting calls from farmers saying that they are continuously seeing these corn-leaf aphids in the fields during the corn-growing season,” said Louis, Harold and Esther Edgerton assistant professor of entomology. “In the Midwest, we’re seeing those increasing reports during the field season.”

When aphids attack

Louis’ team performed its experiments with a line of corn named Mp708, which exhibits callose buildup and a rise in the defense-related protein Mir1-CP. Because Mp708 also features higher levels of OPDA and jasmonic acid, researchers thought that both — the former as a precursor to the latter — were essential to raising those defenses.

Yet the new study indicates that jasmonic acid and benzoxazinoids might not be so essential after all. In one experiment, the team sprayed OPDA on two types of corn plants — one with normal levels of jasmonic acid, the other without — finding that the latter deterred aphids just as well as their jasmonic-rich counterparts. And after exposing OPDA-treated vs. untreated plants to aphids for 24 hours, the researchers discovered that the treated plants had been colonized by roughly 30 percent fewer aphids, which spent less time trying to feed after piercing corn leaves.

The team also measured a corresponding rise in the Mir1-CP proteins, even without increases in jasmonic acid or benzoxazinoids.

“So we’re thinking that if we can activate some of those potent defensive proteins and their downstream defenses, we can provide resistance against the insects,” Louis said. “That’s what we’re looking for.”

Louis now wants to know how the Mir1-CP protein actually affects aphids. His team is also looking for other lines of high-OPDA corn to determine whether they show increases in callose and defense-related proteins when attacked.

More broadly, he said, the team’s recent and future findings might inform the protection of cereal crops beyond corn.

“These crops are equally attacked by many of these phloem-feeding aphids,” Louis said. “So it could be of interest to other researchers working in the area of monocot crops.”

The researchers reported their findings in the journal Plant Physiology. Louis authored the study with Nebraska’s Suresh Varsani and Sajjan Grover, graduate students in entomology; Kyle Koch, doctoral alumnus in entomology; Tiffany Heng-Moss, professor of entomology and dean of the College of Agricultural Sciences and Natural Resources; Gautam Sarath, adjunct professor of entomology; Cornell University’s Georg Jander and Shaoqun Zhou; Texas A&M University’s Pei-Cheng Huang and Michael Kolomiets; W. Paul Williams of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Agricultural Research Service; and Pennsylvania State University’s Dawn Luthe.

The team received support from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture and from the National Science Foundation.