In the 21st century, where information — and disinformation — is shared at warp speed, genocide denialism has spread just as rapidly.

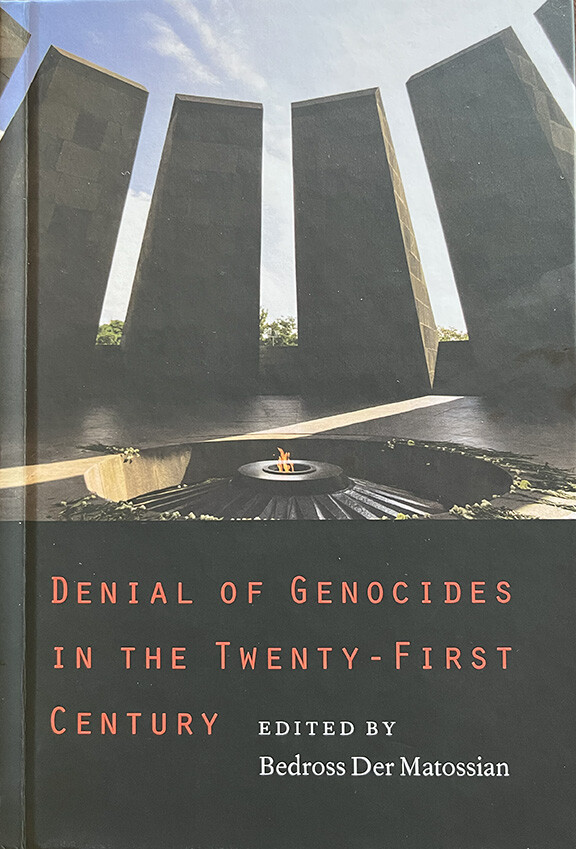

Bedross Der Matossian, a historian of the Armenian Genocide and professor of history at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, is aiming to help explain this phenomenon and combat it with a new volume of scholarship from fellow historians that he’s edited into the book, “Denial of Genocides in the Twenty-First Century.” It will publish May 1 with Nebraska University Press.

“It’s a very timely book, I think, with the rise of right-wing governments around the globe, with the rise of white nationalism in the United States, antisemitism, and with the Turkish government’s excessive propaganda after the 100th anniversary of the Armenian genocide that took place in 2015,” he said.

Der Matossian said the book is an important contribution to the scholarship surrounding genocides in modern history, but it is also important because denialism is a revictimization of the those killed and the survivors, and has wide-ranging unforeseen consequences.

“Scholars argue that the last stage of a genocide is denial,” he said. “Denial is killing the dead, killing the memory of dead, and many survivors live with the denial of their own genocide. The denial of genocides emboldens people to commit additional acts of violence and genocide in the future.”

In chronological order, 12 scholars including Der Matossian write about denialism of eight genocides spanning three centuries. Der Matossian said he asked scholars to contribute based on their expertise as historians of particular genocides. Among the contributors is Der Matossian’s colleague, Gerald Steinacher, James A. Rawley Professor of History, who wrote a chapter about Holocaust denial.

Chapters cover the denialism of the Armenian genocide, genocides of the Indigenous in the United States, the Holocaust, genocides in Cambodia, Guatemala, Bosnia, Rwanda, and the genocide in Syria under the Assad regime. The final chapter is written by Israel Charney, a psychologist and genocide scholar, and explains why some engage in denialism.

“These are examples of major genocides, in order to show why the 21st century is a new phase in denialism,” Der Matossian said. “It endeavors to understand the new methods of denialism that are taking place around the globe.”

While the genocides covered in the book happened, in some cases, centuries or decades ago, Der Matossian noted that the lightning speed with which information is shared today makes is harder to overcome the disinformation.

“Both state and nonstate actors obfuscate the reality through using the medium of social networks, the most important being Facebook, Twitter and YouTube, by putting their propaganda material there, and we see an increase in Armenophobia, Islamophobia, antisemitism,” he said. “All of them are using the 21st century tools to operate and to reach their agenda.”

The volume also raises awareness that genocide denialism does not end, even when countries have accepted responsibility, and it demonstrates that that denialism does not only happen under authoritarian regimes.

“There is no genocide in the course of history that has gone without being denied by states and nonstate actors, often including ‘professional’ historians and pseudo-historians… In the past decade, the rise of right-wing populist governments in Europe and the United States has intensified this trend dramatically,” Der Matossian writes in the introduction.

Der Matossian also challenges his readers to ask themselves what can be done.

“In the United States, the denial of genocide is hiding behind the First Amendment,” he said. “We invite the reader also to raise a question whether denial of genocide should be termed as hate speech.”