Overseas markets provide major revenue for Nebraska’s agricultural sector — about 30% of the state’s annual ag receipts. In 2020, those export sales included $2.3 billion of Nebraska soybeans, $1.2 billion of beef, $1.1 billion of corn and $425 million of pork.

The Nebraska Farm Bureau notes that every dollar in agricultural exports generates $1.28 in associated economic activities such as transportation, financing, warehousing and production.

It pays, then, for farm-state residents to understand the ag sector’s wide-ranging connections to the global marketplace and the need to strengthen opportunities for increased overseas sales.

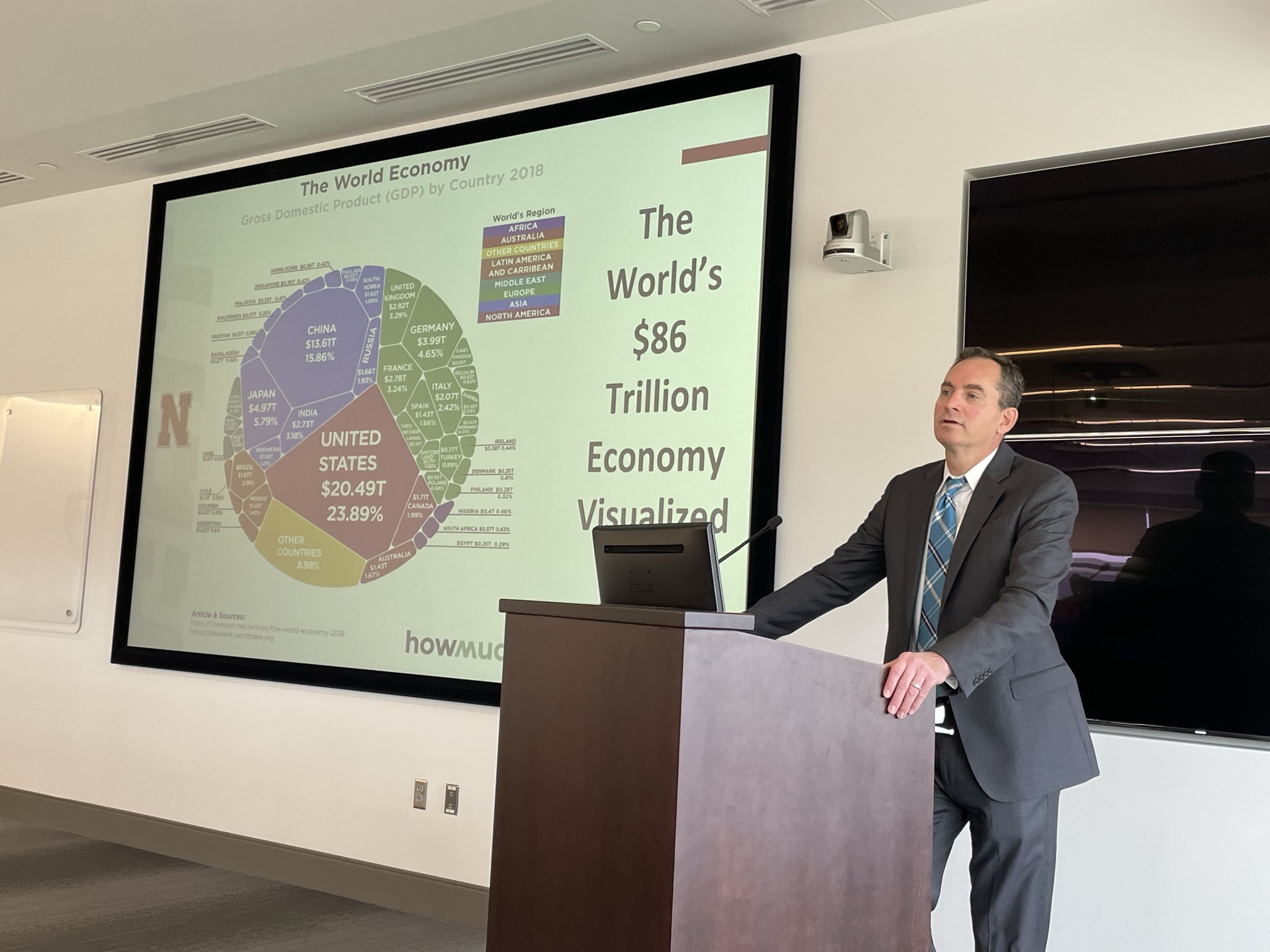

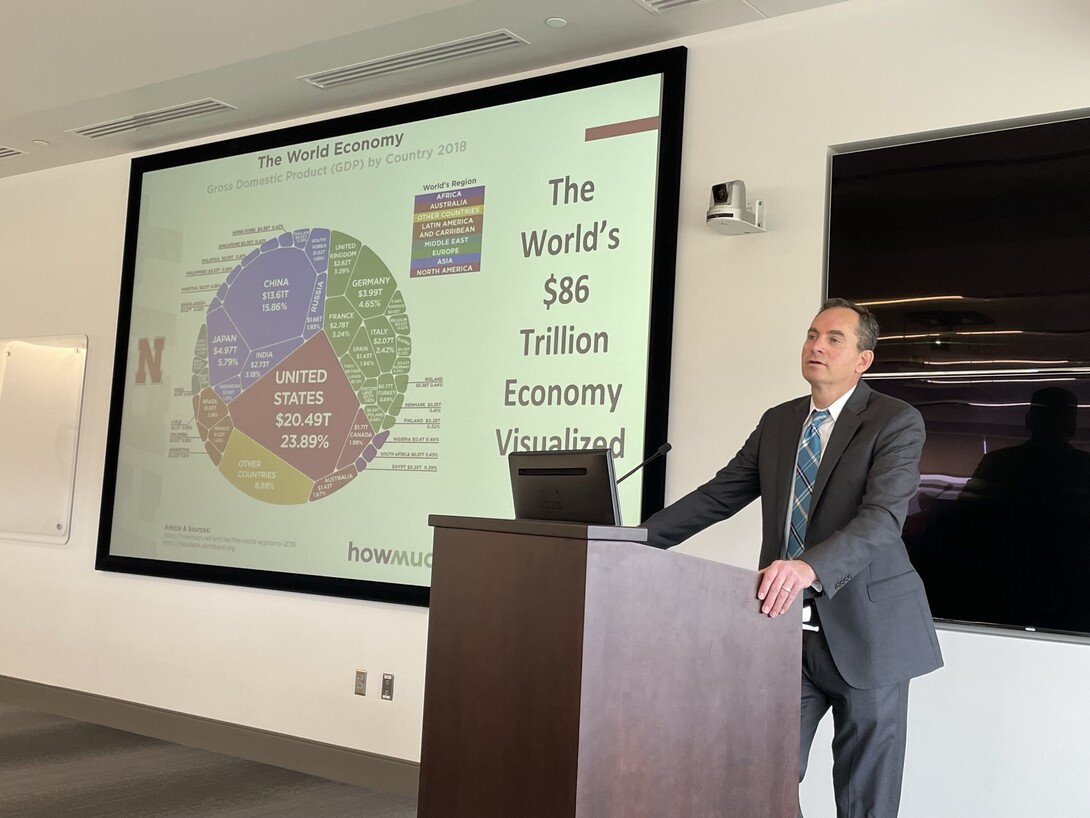

A recent ag-focused conference in Omaha featured presentations by University of Nebraska–Lincoln faculty that explained the fundamentals of international trade. The event, held at the headquarters of Green Plains Inc., also included discussions on how producers can expand the understanding of global trade in their communities and organizations.

The Clayton Yeutter Institute of International Trade and Finance at Nebraska co-sponsored the event along with the U.S. Grains Council. The council and the National Corn Growers Association have offered a series of in-person trade school workshops since 2016. The Aug. 26 Omaha event also received support from the Nebraska Corn Growers Association, Iowa Corn Growers and South Dakota Corn.

The first international negotiations to establish global trade rules took place after World War II and focused on reducing tariffs — the taxes that consumers and businesses pay on imports, Jill O’Donnell, director of the Yeutter Institute, told the audience.

Economist Douglas Irwin has observed that the fundamental issue in trade policy has been the degree to which domestic producers should be protected from foreign competition, O’Donnell noted.

In the second half of the 20th century, countries participating in global trade negotiations reduced trade restrictions, balancing considerations of domestic protection against benefits such as reduced costs for consumers from tariff reductions and increased market access overseas, as trading partners lowered their barriers.

In a series of multilateral trade negotiations from the 1960s to the ’90s, participating countries gradually broadened the scope of negotiations to include reductions in non-tariff barriers, O’Donnell said. That step helped create opportunities for increased agricultural trade in particular, though non-tariff barriers remain a significant obstacle in present-day trade.

Governments adopted the principle that trade barrier reductions negotiated through international talks would apply equally to all participating countries. In other words, each member country would receive the same “Most Favored Nation” status. Under the World Trade Organization, member countries agreed to respect a binding dispute resolution process.

In the United States, the Constitution gives Congress control over trade policy, but Congress has delegated a measure of authority to the executive branch, O’Donnell said. A key example is Trade Promotion Authority, adopted in 1974. Under TPA, a presidential administration negotiates a new trade agreement, and Congress then votes up or down, without amendment, to approve or reject it.

Over the past two decades, this global trade structure has run into multiple challenges, O’Donnell said. Multilateral negotiations under the 164-member World Trade Organization have stalled, and countries instead have relied on a growing number of bilateral and regional trade agreements. The WTO has proved unable to address problems such as industrial subsidies and the complexities of non-market economies, including China’s. The United States has begun taking unilateral punitive actions, such as trade barriers imposed through Sections 232 and 301, which are federal statutes rarely used in the past. The WTO’s dispute resolution process has tumbled into limbo due to a lack of support from the U.S. and other countries.

At the same time, O’Donnell said, skepticism toward open trade has increased among the two U.S. political parties, given the impacts on domestic industry from global interdependence. TPA, used to move trade agreements forward since the 1970s, expired last year, and its revival remains uncertain.

The Yeutter Institute has chair positions in three departments at Nebraska (law, agricultural economics and business), reflecting the interdisciplinary background of Nebraska native Clayton Yeutter, who held private-sector positions and also served as U.S. trade representative and U.S. secretary of agriculture. Two of the Yeutter chairs — Matthew Schaefer in law and

John Beghin in agricultural economics — made presentations at the conference. The third Yeutter chair is business professor Edward Balistreri.

In his presentation, Schaefer explained challenges facing global and regional trade agreements. He described the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework, the trade policy the Biden administration is pursuing with 13 countries. Under that approach, the administration is not seeking the traditional goal in regional trade agreements — reductions in tariffs — but instead is focusing on four themes: trade facilitation; supply chains; clean energy, decarbonization and infrastructure; and anti-corruption.

Beghin briefed the conference on factors contributing to the current global crisis in fertilizer access. Among the factors: strong demand due to solid crop prices. Fossil fuel prices. The Ukraine conflict and sanctions on Russia and Belarus. China’s production shortfalls and export limits. U.S. tariffs on phosphate fertilizer imports from Morocco.

Discussion at the conference turned to the American public’s views on trade, and O’Donnell noted that the Yeutter Institute this year had a podcast with Catherine Novelli, a former trade negotiator and State Department official, offering detailed information on the topic. The podcast was part of the Yeutter Institute’s ongoing series of Trade Matters podcasts addressing a range of trade-related topics.