Bill Belcher, associate professor of anthropology at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, was interviewed for NPR’s “Weekend Edition Saturday” Dec. 16 about The Hump Museum — a new museum in northeast India that features artifacts from some of the roughly 600 U.S. planes that crashed in the Himalayas during World War II. He has participated in several excavations of crash sites there through the U.S. Department of Defense’s POW/MIA Accounting Agency and helped develop the museum.

Belcher explained that so many pilots crashed crossing what American soldiers called “the Hump” — the perilous route over the mountain range that brought supplies from India to Chinese forces battling the Japanese — because storms were unpredictable; some of the planes were newer designs with certain eccentricities; and the planes were flying in excess of tens of thousands of feet, which was relatively new in the 1940s.

“Some of the aircraft that I’ve excavated were some of the first pressurized cabins,” he said. “So there’s that aspect, and there’s just the aspect that we just didn’t know the elevations of some of these mountains. And so a lot of the aircraft crashed right into the side of a mountain because … the maps and the information that they had was incorrect.”

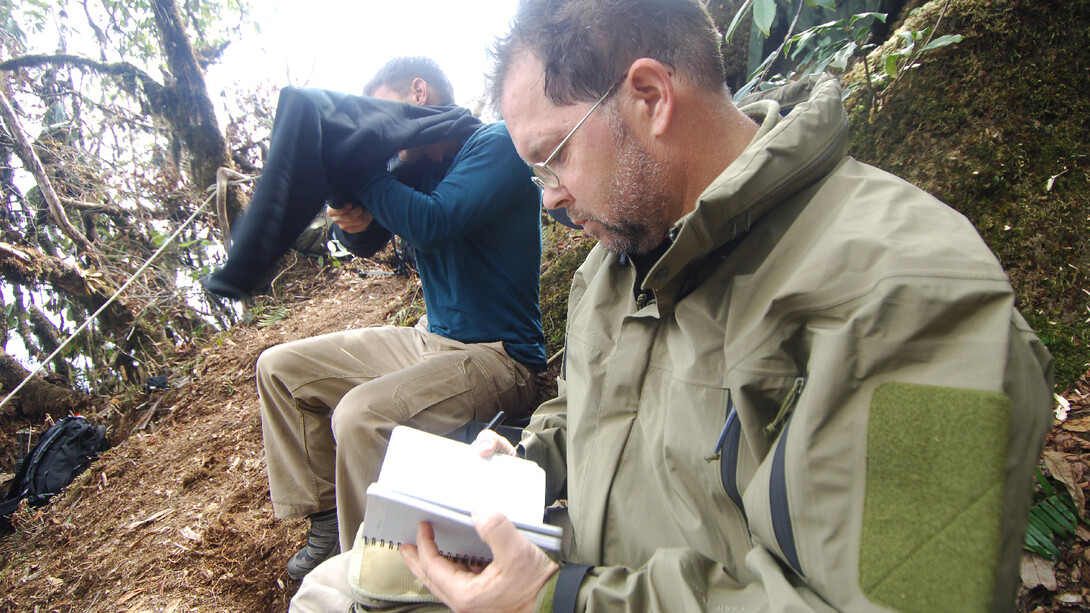

Belcher said excavation teams arrive at the sites by “boots on the ground,” often with the help of local villagers and hunters.

“This is why the museum that has opened up with Oken Tayeng as the director is so important, because Oken owns an outfitting company, so he knows this area extremely well,” Belcher said. “And he’s also from some of the areas we were looking for with some of these aircraft.”

It’s the “little things” he’s found at the sites — personal items such as coins, keys, handkerchiefs, photographs, ID bracelets and dog tags — that have touched Belcher the most. He said the excavations help fulfill promises made by the U.S. government and military, but also by the loved ones of the approximately 1,500 pilots and passengers who never returned from war.

“It’s dealing with promises and expectations, I think, that we make to each other: from one sibling to another, to our spouses, to our children. And our children make these promises to our parents, that we’re going to do everything we can to make sure that you’re home,” he said. “I think when we think about it in a contemporary living sense, it’s like keeping everybody safe. But that continues on after death, where we want to bring people home.”

For more information on the School of Global Integrative Studies at Nebraska, click here.

Nebraska Headliners highlights Husker faculty and staff featured in major news outlets. If you see a possible Nebraska Headliner, submit the story or URL via email to nebraskatoday@unl.edu.