About 20 minutes south of Lincoln, off the well-worn gravel roads is a grass and dirt path leading into the Reller Prairie Research Station.

After standing relatively vacant for a decade — save for its wildlife occupants, some curious humans and a handful of academic researchers — faculty and staff from the University of Nebraska–Lincoln’s schools of Global Integrative Studies and Biological Sciences are breathing new life into the property.

The rehabilitation began two years ago when Sophia Perdikaris, director of the School of Global Integrative Studies, learned about the Reller Prairie through Jon Garbisch, associate director of the Cedar Point Biological Station near Ogallala. She’d been looking for resources and locations to boost experiential learning in classes and field schools, so she and William Belcher, associate professor of anthropology, drove out to take a look.

The property was in need of some updates. The building, which was originally built as a storage shed, would require some renovations to be used for classes again and the trees and brush had become overgrown. Despite the work involved, Perdikaris immediately saw its potential as an indoor/outdoor classroom where students could do anthropological digs and testing, and biological sciences students could see plant and wildlife ecosystems up close.

“It had kind of been forgotten,” Perdikaris, Happold Professor of anthropology, said. “I’m an environmental archaeologist. I have a soft spot for things that are old, and as time goes by, they get scarred by the passage of that time and are forgotten. They provide incredible opportunities for knowledge and discovery and I get great pleasure in sharing that with colleagues, students and the community.”

As an institutional research area, the property has a long history. Perdikaris and LuAnn Wandsnider, associate director of the School of Global Integrative Studies, traced it back to the 19th century. A large piece of land that includes what is now Reller Prairie was first granted to Brown University in 1866 through the Morrill Act. There are few records of Brown University’s use of the area, but it was eventually purchased by the Reller family. The family gifted an 80-acre parcel to the University of Nebraska Foundation for use by the University of Nebraska State Museum in 1970. Eventually, it became a research and education station for the School of Biological Sciences. Paul Hanson, professor of geology, located aerial photos from the 1940s to today, showing how the property has changed.

Its mission for the university has changed, too, over the years. Garbisch noted that as the museum’s mission changed, Reller was merged into the School of Biological Sciences, and was used heavily for research and classes from 1985 to 2000.

“I found a lot of vegetation plots from studies that were done at Reller in the 1970s and 80s,” Perdikaris said.

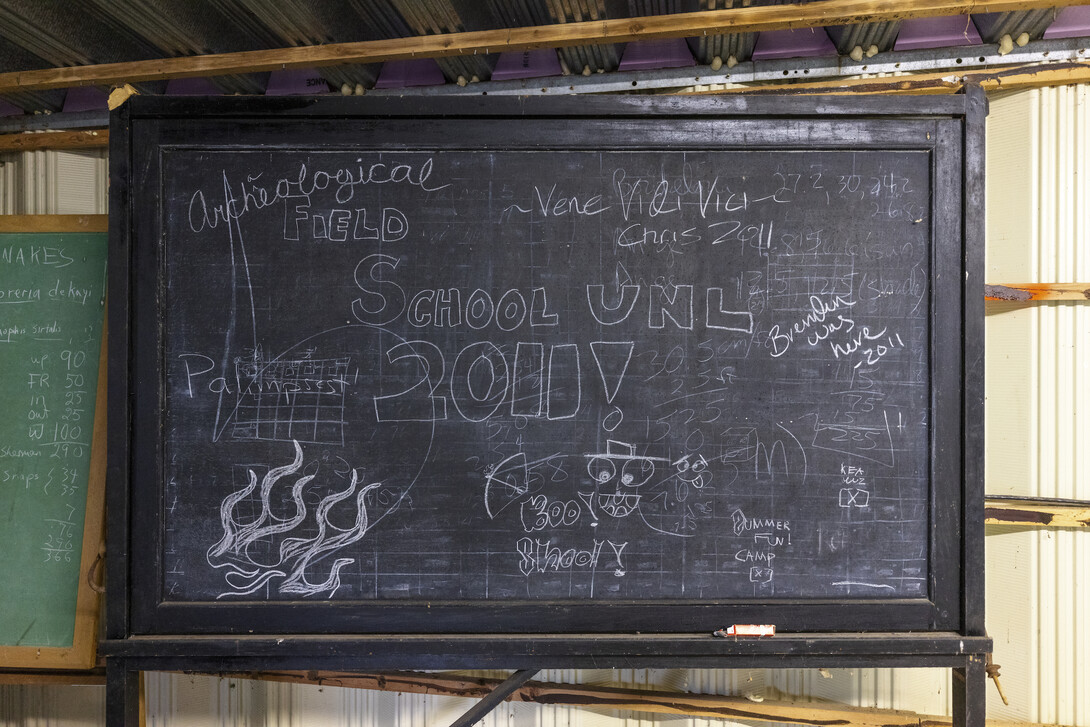

But then it went mostly unused for a decade. The first time Perdikaris entered the classroom building, there were still notes on the blackboard from 2011, the last time a class had been held there. On another blackboard, someone had left notes and a map showing the last controlled burn of the parcel in 1985.

Perdikaris was determined to make Reller Prairie Research Station functional again as a teaching space. She asked colleagues in Global Integrative Studies, Biological Sciences and the School of Natural Resources for their expertise and help in cleaning up the property, along with evaluating the preservation and conservation strategies for the proper restoration and recovery of the prairie, forest and building facilities. Groups of volunteers spent at least one Saturday per month helping gut the building, trim trees and brush, mow paths and remove invasive cedar. Perdikaris also donated her own funds to purchase new signage and picnic tables for outside and new furniture and hardware for the indoor classroom.

“I took some money from my start-up (funds), some happy volunteers and we got to work,” she said. “The grasses were taller than I am, and we had to redo the structure. I’m so thankful to our volunteers because it wouldn’t be possible without them.”

Garbisch helped advise the group on which invasive species needed to be removed and worked alongside the volunteers during the cleanup. Perdikaris also had regular help from Wandsnider; Belcher; Kat Krutak-Bickert, unit coordinator for the School of Global Integrative Studies; and Michael Herman, director of the School of Biological Sciences.

The work of the group, which often included additional colleagues and students, paid off when Belcher taught Forensic Anthropology at Reller, where students excavated simulated burials, and Wandsnider brought the Lithics course to flint knap and make stone tools in fall 2020.

In June, Phil Geib, assistant professor of practice, led the first School of Global Integrative Studies archaeology field school on the property.

And just as Perdikaris had hoped, the larger community is benefiting from Reller, too. Belcher taught a field training course on forensic recovery for the Omaha Police Department.

There’s still work to be done, Perdikaris said, but she is happy with how much the group has accomplished and is excited to continue improvements, including more signage, more brush and cedar removal, and installation of insulation in the classroom to allow year-round use. She is actively seeking additional funding, including grants and other financial and materials donations.

“We want to have Reller as an outdoor training and community learning node,” Perdikaris said. “We have been talking with the Science Focus Program of the Lincoln Public Schools, and we’re hoping to have community groups such as Scouts and Montessori schools use it, along with our classes. It’s a great collaborative environment where everyone can bring the richness of their discipline and students from different disciplines can interact with one another and collaborate in the field.”