When Bing Chen and Jerry Varner first started working for the University of Nebraska in electrical engineering in 1965, the center of their academic world was Ferguson Hall.

As teaching assistants, it was there that they taught labs, did research, prepared lectures, took classes — Varner pursuing his master’s degree and Chen as a third-year undergraduate — and began making the thousands of personal connections that continue to fuel their work today as faculty in the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering.

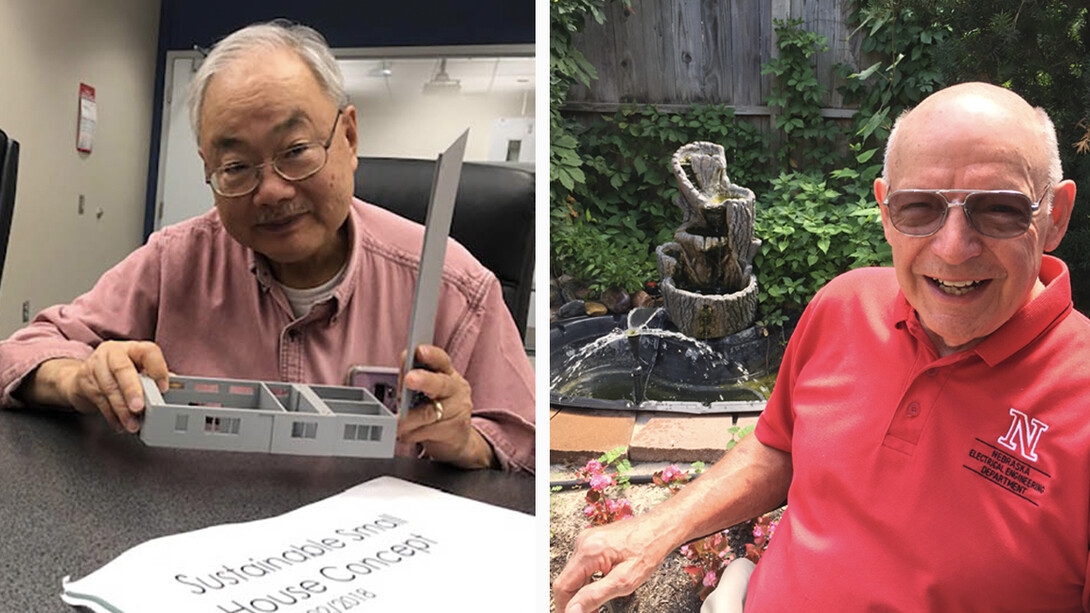

Among the nearly 1,000 University of Nebraska–Lincoln faculty and staff who will be recognized on Oct. 19 at the annual Celebration of Service, Chen and Varner are the longest-serving honorees.

“We’re a long, long way from Ferguson Hall,” Chen said of the former home of the electrical engineering department. “It may be gone (torn down in 2010), but that’s where we learned all the things that would create the foundation for our careers.”

The views from the third-floor offices in the 1960s afforded the teaching assistants a panorama of the entire City Campus.

“It was a great way to take a break from grading papers or preparing for classes,” Chen said. “I remember Big Red practicing on the Memorial Stadium field, and you could see them from our windows because the South Stadium had not yet been built, and you could hear them, too. One time I heard Bob Devaney’s voice, and it was obvious he was unhappy about something.”

Varner recalled the value of camaraderie among the electrical engineering faculty and graduate students.

“You talk about differences between now and then, it’s entirely different times now,” Varner said.

“In Ferguson Hall, in the basement there was the faculty lunchroom and most would go down there, eat lunch together and talk about the day’s problems. Now, technology has changed the way we work. We have shiny labs and nicer offices, and we lock the door and eat lunch alone so we can get more work done.”

Though time has passed, and the delivery of lessons is constantly changing, the one constant for both Chen and Varner the past 55 years that the students come first.

“Bing and Jerry have always been interested in each student’s professional success, not just how they were progressing in their coursework. The overall well-being of the students is always their chief concern,” said Jerry Hudgins, chair of the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering.

Chen said it’s a philosophy he learned from watching his professors.

“They made me realize the technical side of engineering is a fairly minor part of the education process, and that my job is about showing them how to become a professional engineer, how to be a better human,” Chen said.

“If I can train students to be contributing members of society, help them to think about others, that’s probably as important to their being an engineer as learning Ohm’s Law,” Varner said.

These are lessons each has carried with them for more than a half century.

A Seward native, Varner came to the university in 1959 to study electrical engineering with the goal of working one day in industry.

“I was married and had two kids, and the motivation to get a master’s was that I could make a little more money,” Varner said. “Carrie and I never planned on staying in Lincoln for long. But after teaching for a while, my opinion about why I was here changed to wanting to teach and make a difference in people’s lives.”

After earning a master’s degree, Varner was hired on as a full-time instructor, a position he held until earning a doctorate in 1972 and becoming an associate professor.

Varner gained plenty of connections outside of academia, including collaborating on research at the University of Nebraska Medical Center and serving 15 years as a consultant with the National Institutes of Health in Washington, D.C. The lure of moving on was strong, but the connections he and his family had to Nebraska were even stronger.

“Washington became sort of a second home to us, but if we were to go anywhere, we’d have had to have broken all the ties here,” Varner said. “There were plenty of opportunities to leave, but the attraction just wasn’t as great as it is at home.”

Chen came to Nebraska in 1963 after graduating high school in New York City. It was a nudge from an uncle that convinced him to check out the university.

“My uncle told me, ‘You’ll like it here in Nebraska, the teachers really care about their students.’ And, you know what, he was right,” Chen said. “That, to me, was the difference in my deciding to stay rather than returning to the East Coast. And I stayed for an entire lifetime.”

Though he was two years from earning his bachelor’s degree, in 1965 Chen was hired as a TA by electrical engineering chair Allen Edison and by 1967 was teaching the department’s freshman labs.

After earning a bachelor’s in 1967, Chen joined Harry Meyers in starting the computer and electronics engineering program in Omaha, eventually becoming a full professor in 1981 and then serving as department chair from 1997 until the program later merged with the electrical engineering program.

Chen and Varner remain educators at heart and continue to have an impact in the College of Engineering classrooms and labs.

But the memories of those early days still have a strong pull.

“When I started in 1959, there wasn’t even a hand-held calculator, we used slide rules. When I taught, I carried chalk and an eraser with me because a lot of times the classrooms didn’t have any,” Varner said with a chuckle. “Now, electronics has changed everything, and I guess we engineers are responsible for making all those things obsolete.”

“I miss those little things, like Ed Lowenberg’s way of having the office door open and always being willing to chat with you. That’s something I try to maintain in Omaha, and Jerry does in Lincoln,” Chen said. “Sometimes, I wish we could move back to Ferguson Hall. There was a certain magic there.”