· 6 min read

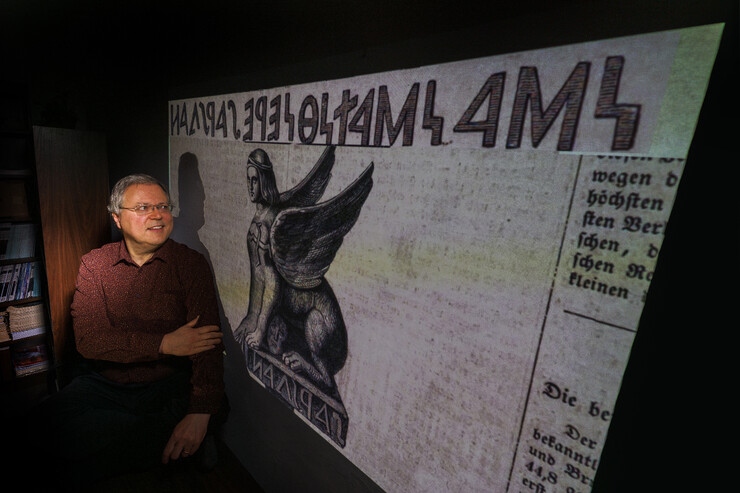

Revesz decodes ancient sphinx’s mysterious message

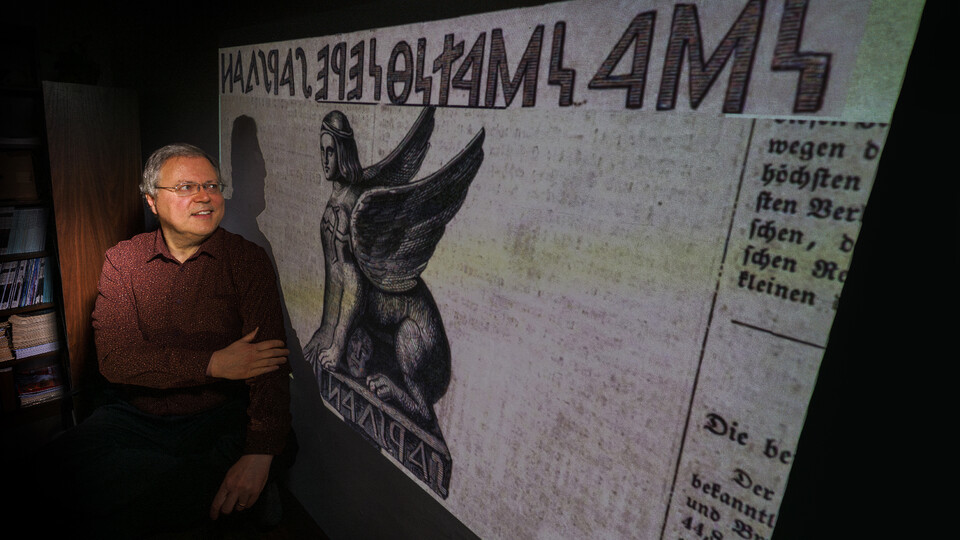

For nearly two centuries, scholars have puzzled over an inscription of just 20 characters, cast upon an unusual bronze sphinx statue believed to have originated in Potaissa, a Roman Empire military base camp located in present-day Romania.

Peter Revesz, a University of Nebraska–Lincoln expert in computational linguistics, recently made headlines in approximately 50 news articles from around the world when he solved the mystery.

“Lo, behold, worship! Here is the holy lion!” is his translation, revealed in the January issue of Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry. Based on his experience using databases to compare and identify alphabet symbols and languages, Revesz concluded the inscription uses an archaic Greek alphabet to convey words in a proto-Hungarian language.

In addition to the Miami Herald, stories about Revesz’s discovery appeared in Arkeonews, Archaeology News, Greek Reporter, Stile Arte and GEO.fr.

A crucial clue to identifying the alphabet was the realization that, not only was the inscription written right to left, but its characters were rendered as mirror images of alphabetic symbols.

Once Revesz identified the language as an ancestor of Hungarian, the puzzle pieces fell neatly together. He recognized that the inscription uses deliberately alliterative language in a poetic meter – an accented syllable followed by two unaccented syllables.

“This is what I think is a poem,” Revesz said. “It fits together with the statue itself, a winged lion. It seems to be relaying a prayer line or perhaps a hymn of a minority religion.”

The statue’s base included a spike for it to be inserted into a pole, which possibly allowed it to be used in religious processionals as a flagpole or standard bearer, Revesz added.

A member of UNL’s computer science faculty since 1992, Revesz describes himself as an interdisciplinary scholar. He holds a courtesy appointment in the university’s Department of Classics and Religious Studies.

Revesz said his work is an example of how computational techniques can be used to understand history and language. Another example of the growing field of study is when Nebraska computer science major Luke Farritor used artificial intelligence to decipher words on a charred papyrus scroll that was nearly destroyed in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in A.D. 79.

Revesz has loved ancient history and language since he was a child. He credits Paris Kanellakis, his doctoral adviser at Brown University, for fostering those interests.

Kanellakis was a renowned computer science scholar who was also fascinated by the undeciphered ancient writings of the Minoan civilization. On his desk, he kept a replica of the Phaistos Disk, a Minoan artifact that was covered on both sides with a spiral of stamped symbols. Revesz, who began deciphering ancient inscriptions in 2008 while teaching at the University of Athens as a Fulbright visiting professor, later used computational linguistics to decode the inscription on the Phaistos Disk as a hymn to a solar deity. Also using computational linguistics and mathematical methods, Revesz discovered that the Minoans wrote much about nature, female deities and cave spirits on 28 Linear A inscriptions. Kanellakis tragically died at age 42 in the 1995 American Airlines Flight 965 crash in Colombia and did not live to witness these exciting developments.

Deciphering the Potaissa sphinx offers insights about minority religions during the Roman Empire, as well as how widespread the Egyptian-derived sphinx cult became before Christianity grew dominant, Revesz said.

“The translation not only satisfies many researchers’ curiosity, who have pondered this artifact over decades, but it contributes to a broader understanding of cultural life in the Roman province of Dacia (where Potaissa was located) in the third century,” he said.

Although the sphinx was found in a Roman province, sphinx worship was not part of the mainstream ancient Roman mythology that featured Jupiter, Juno, Minerva and other gods and goddesses that remain familiar to many even today. Revesz said the Potaissa sphinx is evidence that provincial culture was a complex composition of ethnic groups, with influences that could be traced back to Greece and even further to Egypt.

Many mysteries remain about the little statue, including its whereabouts today. It was acquired by an art collector, Count József Kemény, in the first half of the 19th century, and its provenance is uncertain. The statue disappeared when Kemény’s estate was looted during the Hungarian War of Independence in 1848-49.

Revesz based his detective work on a detailed drawing of the sphinx and its complete inscription that appeared in Illustrirten Zeitung, an illustrated German news magazine, in 1847.

In a paper about the Roman Empire’s minority sphinx cult, archeologist Adam Szabó of the Hungarian National Museum wrote that the statue likely was associated with a sanctuary where the Egyptian goddess Isis was worshiped.

With a female head and winged lion’s body, along with a sun symbol on its chest, the Potaissa artifact bears resemblance to both the sphinx of the Naxians, given by the people of Naxos to the Temple of Apollo at Delphi in Greece, and the Pazyryk sphinx, a central Asian artifact that dates to the Iron Age. In a Youtube video about his research, Revesz describes the dispersion of sphinx and sphinx-like objects across thousands of miles in the Middle East, Europe and Central Asia.

Romanian archeologist Nicolae Vlassa attempted to translate the inscription into Greek in a 1980 paper. However, Revesz found Vlassa’s translation unconvincing, due to decipherment errors Revesz explains in his research publication. Revesz suspected that, instead of Greek, the inscription used Greek characters to phonetically convey a language that lacked its own alphabet.

Revesz, who was born in Hungary, noticed that the final six characters, when mirror imaged and rearranged into left-to-right order, resembled “arslan” – a Turkic word for lion that became part of the Hungarian language. Other characters resembled Hungarian words for “worship” and “lo, behold” and an ancient Greek word for “holy”. Some evidence indicates proto-Hungarian speakers were resettled into Dacia after Romans colonized the region.

“It is well-known that the Roman Empire contained diverse populations and languages,” Revesz said. “Studying this statue feels as if the winged sphinx has flown to us from the distant past and also brought us a message.’”