A new study co-authored by University of Nebraska-Lincoln researchers has found that nitrogen-based fertilizers used to grow crops in California’s Imperial Valley may also cultivate air pollution faster than previously thought.

Led by the University of California, Berkeley and University of California, Riverside, the study measured levels of fertilizer-released nitrogen oxide, a gas that contributes to ozone formation in the Earth’s atmosphere.

Emissions recorded during the study represent some of the highest ever reported and far exceed model-based projections conducted at UNL, the authors said.

The emissions generally increased with the amount of fertilizer applied, especially when temperatures rose above 80 degrees Fahrenheit and soared as high as 104.

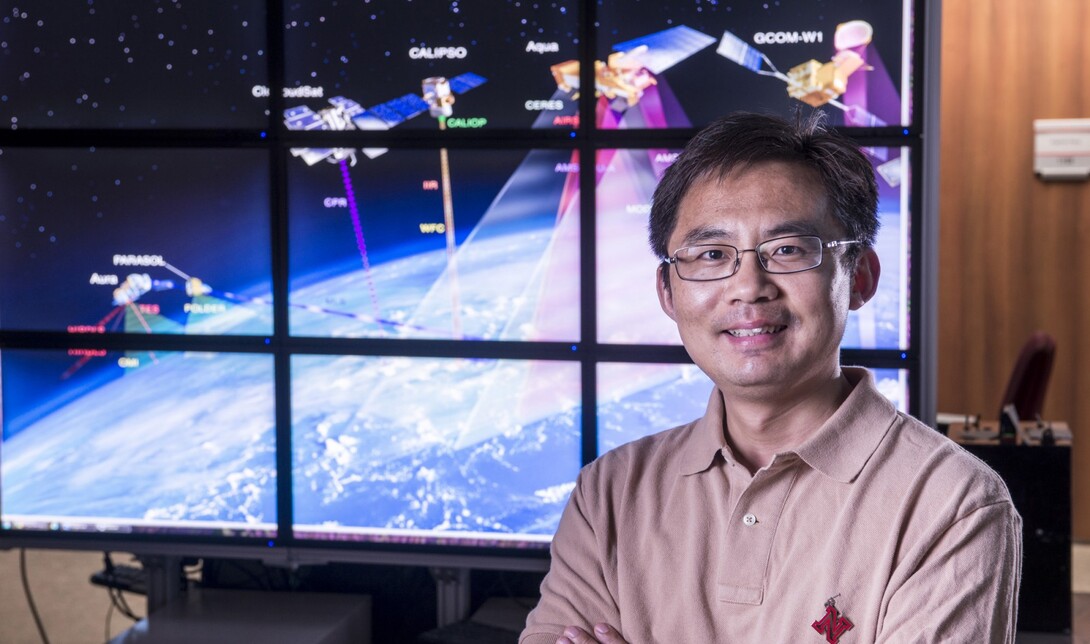

“(Current) air quality models are insufficient in describing how much (nitrogen oxide) emission is coming from the soil during agricultural practices in high-temperature conditions,” said Jun Wang, a contributing author and Susan J. Rosowski Associate Professor of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences at UNL.

Yet the study echoed previous research in showing that nitrogen oxide emissions generally fall when splitting the same amount of fertilizer across many smaller doses, rather than few larger applications. The authors further determined that injecting a dry fertilizer into soil generates lower emissions than depositing a liquid form on the surface.

The latter findings could help guide environmentally conscious practices in the face of a warming climate, said Wang.

“Proper consideration of atmospheric information in the management of irrigation and fertilization can reduce ozone formation and improve air quality,” he said.

UNL postdoctoral researcher Cui Ge also contributed to the study, which was published by the journal Nature Communications.