Polarizing societal issues, as told in three acts. Sharks with frickin’ laser beams on their heads. Impostor syndrome and failure. A literal straw man named Steve. Fun with manure.

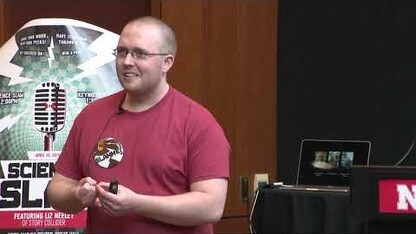

The University of Nebraska-Lincoln’s fourth annual Science Slam had them all.

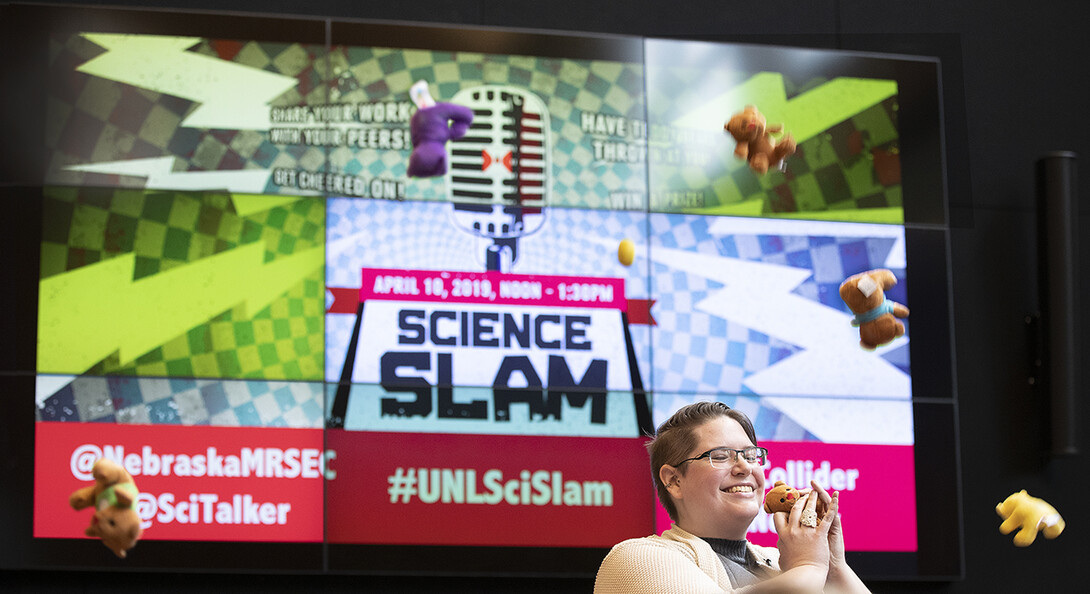

“This is literally the most fun thing to do as a grad student in academia,” said Alice MillerMacPhee, a three-time veteran of the event.

Held April 10 at the Wick Alumni Center, the event gave MillerMacPhee and four other performers a stage to share their science while answering a timely question: What’s the biggest misconception people have about your field or scientific research in general?

MillerMacPhee started first. The grad student in sociology ended that way, too, winning a plurality of votes from a 100-strong crowd that flung a potpourri of miniature teddy bears and plush emoji faces toward the stage to signal its approval.

In her performance, “There’s a Method for That,” MillerMacPhee played the role of each side in some of America’s most flammable debates: Is pornography a public-health issue? How do perceptions of U.S. farms and small-town life compare with the realities? What are the implications of immigration policy for rural areas?

Throughout the 10-minute talk, she also laid out how the tools of sociological research are addressing those very issues.

“The reason I keep coming back is because I think, too often, we (just) do research — which means we sit in a lab or in our offices — and we speak in academic journals,” MillerMacPhee said. “This forces you to be able to talk to everybody about what you’re doing and why you care about what you’re doing. This is legit skills training, in my opinion. It’s a total blast, and it’s making me a better scholar and a better communicator.”

Dan Haden, who researches at the university’s Extreme Light Laboratory, broke out a pair of safety goggles and references to Dr. Evil while describing how people react upon learning that he works with lasers 1 billion times brighter than the sun.

No, Haden explained, he doesn’t use the lasers to blow stuff up. In fact, the lab’s work may actually help prevent that outcome by generating X-rays potent enough to detect tiny amounts of uranium hidden behind inches of steel.

Another popular misconception — that great scientists are born, not trained; that they succeed, not fail — received the debunking treatment from Nicole Benker. Benker recently graduated with a bachelor’s degree in physics and astronomy despite failing a physics course multiple times and battling the impostor’s syndrome that many young academics admit to experiencing.

But after detailing a series of memorable struggles and gaffes, Benker revealed that hiring committees from two national laboratories had reached out to her in just the past few days — a moment that drew booming applause from the audience.

Andrew Conner poked fun at the obscurity of his field, commutative algebra, by asking a straw-filled stage companion to share what he knew about it, then milking the deafening silence he got in response. And he conceded that explaining his corner of mathematics in the allotted 10 minutes would prove tough.

Instead, he described how studying it makes him feel. Comparing himself against the field’s giants — “literally some of the smartest human beings in history” — can be overwhelming, he said. Yet he also compared the wonder of coming across certain theorems to the bracing jolt of a deep breath on a brisk winter day.

The event’s final presenter, Agustín Olivo, explained the jolt of bewilderment he felt when reading an email from his lab’s faculty leader: “All looking forward to fun manure times tomorrow?!” The grad student in biological systems engineering was initially dubious, he said.

But Olivo eventually came to appreciate the numerous ecological benefits of manure, which he called “the wonder drug of soil.” He wrapped his performance by pulling up proof: a photograph of the manure-themed slippers he now owns.

Jocelyn Bosley, the Science Slam’s co-founder and perennial host, said she hopes the event will help this year’s performers — and the scientists in attendance — gain fresh perspectives on the false impressions of science that the public sometimes adopts.

“I think it’s great training for them to think not only about the misconceptions that people have, but also: Here’s why that’s a misconception, and here’s how I can correct it,” said Bosley, assistant director for education and outreach at the Materials Research Science and Engineering Center. “I think that resonated with a lot of people who are clearly frustrated about misconceptions that exist throughout their fields, but also forced them to realize that they have an active role to play in correcting those misconceptions.”