As it did so many others, the onset of COVID-19 upset the best-laid plans of Nebraska U’s Scott Gardner and Judy Diamond.

For years, the duo had recruited high school teachers from across Nebraska to workshops focused on Earth’s most abundant life form: parasites. As curator of the university’s Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology, home to the second-largest collection of parasites in the Western Hemisphere, Gardner provided the subject-matter expertise. Diamond, a longtime professor and curator of informal science education with the University of Nebraska State Museum, helped convey that subject matter in ways engaging and accessible to the teachers and, ultimately, their students.

Then came SARS-CoV-2. But if a virus — invisible and oft-ignored when not igniting a pandemic — could temporarily put their outreach efforts out of reach, well, Gardner and Diamond figured they could find another way to spread the word about the similarly hidden, overlooked realm of parasites. In 2021, the faculty worked with Gábor Rácz, a collection manager at the state museum, and Brenda Lee, an illustrator and Husker alumna, to craft “Parasites: The Inside Scoop,” a book intended for younger readers.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Who’s the audience for this book?

We wrote it for anybody interested in parasitism. Basically, it’s a primer on global parasite biodiversity.

The idea was to put this out … for people who just want to understand what parasites are and how important they are in the world. I think this does it.

How did you and Judy collaborate on the book? What did that process look like?

A lot of the stuff that’s more interesting for people to read, Judy wrote, because I’m more fact-based, hardcore-scientific. So I would write, and she would say, “Well, people don’t want to read that. They want to read something like this: ‘The planet is losing (parasite) species faster than scientists can name them, much like burning a library without knowing the names or the contents of the books.’” She came up with that idea, and I thought, “Wow, that’s wonderful.”

So she was able to write this stuff and make it relate to people in a way that’s more visceral than I could do it. That’s where we really worked together. I was able to put in some of the data about the number of species that are being lost daily, and then she was able to take these other humanistic things and put them together. So that was really cool.

Judy also worked with me and Gábor to guide Brenda in her illustrations of parasite life cycles. This presents the life histories of parasites in a comic format to make them more easily understood. As far as we know, no one has ever attempted this in a published work.

And Gábor took the lead in writing a guide to parasites mentioned in the book that’s included in an appendix. That section includes Brenda’s terrific illustrations of the parasites.

What biological, ecological or evolutionary lessons do you hope readers will take away from the book?

Well, one of the things that I hope that they can see is how complex this stuff is. It’s not simple at all. When you go into an area to do a study, for instance, if you don’t pay attention to the parasite fauna in the mammals or the insects or anything else, you’re missing over half the species. So what I want them to understand is that parasites are everywhere, whether they’re pathogenic or benign.

Parasites are hugely diverse. They occur in everything. … If you walk out to the Sandhills anywhere in Nebraska, from Norfolk all the way to Ogallala, you will see pocket gophers every 20 meters. And those are all full of these different kinds of parasites.

And some (parasites) have extremely complex life cycles that are very, very difficult to tease apart. … The parasites are always probing for new hosts. If a pocket gopher is living in a burrow, and along comes something like a mouse or a vole, it might become infected with some of the parasites that the pocket gopher had, because it happens to ingest an intermediate host that it wouldn’t normally hit unless it goes into that burrow.

Many of the book’s 13 chapters are devoted to case studies that illustrate, say, the complexity of those life cycles or the ways that human-driven factors are curbing parasite diversity. If you had to pick just a few, which are your favorites?

We talk about the discovery of a new species of tapeworm from where I grew up, when I was a kid (in Oregon). I started looking at gophers there when I was young, and all of them — every single one in that area — was full of tapeworms. Now, when you go there, there are none in the gophers in that area. We’re not sure if it’s because of farming practices or because things have changed in other ways.

But diversity is often linked to intermediate hosts. Almost no tapeworms can live inside a mammal unless their eggs go into a beetle or a mite first, where it develops into a larva. So, depending on the species, an egg has to be taken up by a beetle or mite or maybe a springtail, and then it has to be re-eaten by the mammal in order for that cycle to work. And that complexity is well-illustrated in the book.

Your uncle, Robert Rausch, helped verify that you had discovered a new species, right? And some of his work is featured elsewhere in the book?

My uncle was really one of the foremost parasitologists in the world at the time. I went to study at the University of Alaska with him as an undergraduate. In the 1950s, before he was head of the Arctic Health Research Center, his research team discovered that, like, 70% of the people who lived on St. Lawrence Island were infected with larval-fox tapeworms. The older a person was, the more likely it was that they had this tapeworm. It was because the dogs that they were living with were all infected. And these tapeworms are really tiny — only about 3, maybe 4 millimeters long. … After ingestion of the eggs, usually they get stuck in the liver, and they start to grow into his thing that looks like a metastatic tumor. So you don’t even necessarily know you’re until infected until maybe 20 years (down the line). This tapeworm, we’re working on now, and we have recently published on the expansion of the range of this species into New Mexico and Maryland.

There’s also a chapter dedicated to the world’s largest parasite, which can grow to more than 100 feet long.

(There’s a replica of it) hanging above the parasite display at the University of Nebraska State Museum. It’s stunningly huge.

It lives in whales, and the eggs are produced by the hundreds of millions. Because it’s just a crapshoot; it’s a completely random thing. Those eggs go out, and then they have to be eaten by a (crustacean) or something. Then that (crustacean) has to be eaten by a fish or krill, and then it amplifies up in that fish or krill, and then the whale eats the krill and becomes infected again.

How does the book reflect the scope and mission of the Manter Laboratory of Parasitology?

We wanted to give a broad perspective on the kind of work that we do here at the Manter Lab. This is one of the leading museum laboratories in the world for parasitology. The diversity that we have here, it’s really intense, it’s really broad. … Literally thousands of people’s collections have come into this one.

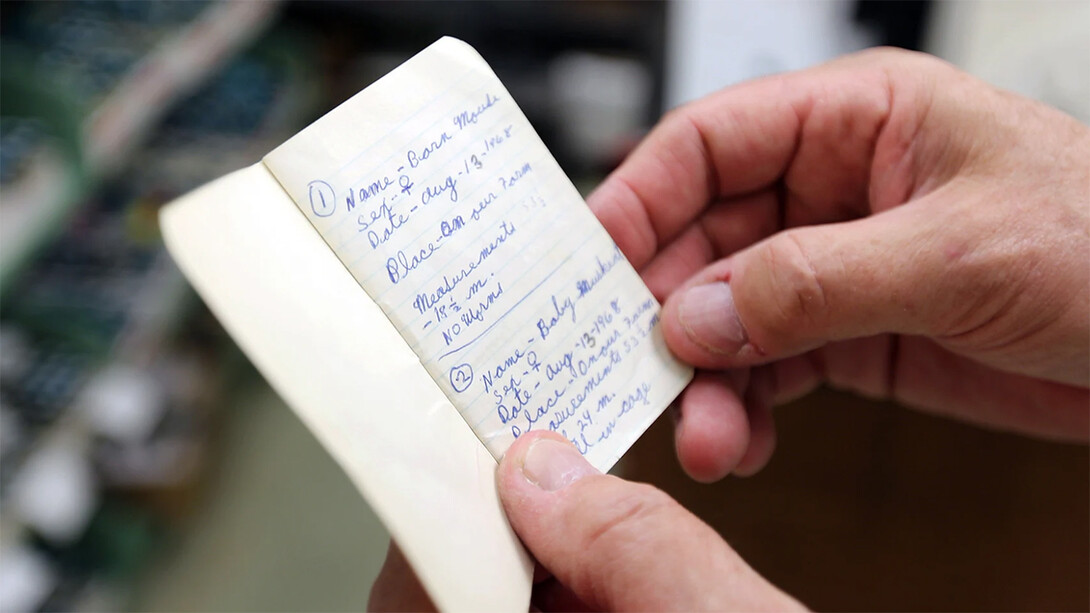

If you look at how much time it takes to collect a specimen and put it into a vial, and then label the vial, and then put the vial into the collection, and then take the specimen out and put it onto a slide and make a permanent slide of it that then goes back into the collection, and then take images of it… The number of hours that have been put into this biological collection by our people is billions of dollars’ worth, because we have more than 500,000 microscope slides in the collection now, and in excess of 100,000 vials with specimens.

These things that we publish, that are based on specimens in the collections, are the basis for understanding diversity forever. … Everything we put in these collections, we assume it’s going to last 10,000 years. When we put (a specimen) in a bottle, we use formaldehyde that’s buffered, or we use ethanol. We also write on it in India ink, or indelible ink, that will never degrade. And we use a lid that’s Teflon-lined so that it will not leak. This bottle was designed to last in our collection for as long as humanity lives.

How many copies of the book are you giving as presents this holiday season? Who’s getting them?

The lab bought 60 copies. They’re going out to a lot of the science teachers in Lincoln who signed up for our workshops … so they could take ideas about parasitology back to their classrooms. All those teachers are going to get copies.

And I’ve already sent out about 20 copies to various people we’ve worked with over the years. I sent one to Bill Campbell, who won a Nobel Prize for the discovery of (the antiparasitic drug) ivermectin. … He wrote me, and he said, “Scott, I received the book. I read it cover to cover, and it’s amazing.” It was pretty neat to get a letter from a Nobel Prize laureate saying that he loved the book.