An innovative program to help teachers solve classroom behavior problems also helps parents reduce temper tantrums and disobedience at home, a new study shows.

The experimental program — known as Conjoint Behavior Consultation, or CBC – teams teachers and parents with specially trained consultants who work together to defuse problem behavior and improve school performance.

Experts from the Nebraska Center for Research on Children, Youth, Families and Schools at UNL recently launched training workshops to encourage more educators and others who work with children to use the family partnership techniques developed and tested through the center’s rigorous research protocols.

“One of the things we have learned from our research is that family engagement in education is unequivocally one of the best ways to promote children’s success,” said Brandy Clarke, a research assistant professor leading the new training program.

Though educators and parents alike recognize the importance of working together to help students, few methods have been developed to foster such partnerships, particularly when there are problems that need to be addressed.

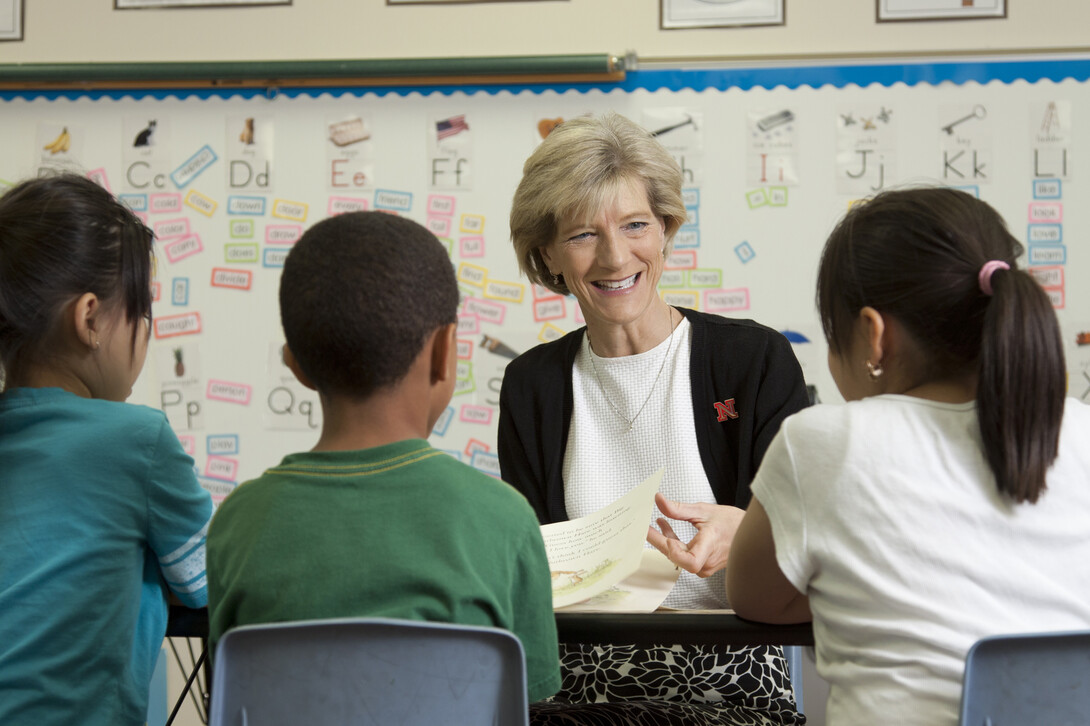

It is the students who suffer when tensions over their behavior problems lead to a strained or adversarial relationship between parents and teachers, said Susan M. Sheridan, a UNL educational psychology professor who heads the Nebraska Center for Research on Children, Youth, Families and Schools.

The CBC program — also known as Teachers and Parents as Partners — focuses on positive approaches to working together, smoothing the rifts that commonly occur and creating multiple opportunities for solving problems, not increasing them, she said.

Past research demonstrated that the method reduced school behavior problems for participating students. The most recent study, published late last year in the Journal of School Psychology, showed the approach also improved children’s behavior at home. This study complemented related findings that CBC effectively improved social skills and behaviors at school, as well as relationships between parents and their children’s teachers.

The randomized, large-scale trial followed 207 kindergarten- through third-grade Lincoln-area students. It found that children were less argumentative and defiant at home after participating in the program. Teacher-parent communication improved and parents developed better problem-solving skills to deal with misbehavior.

Sheridan said the CBC program works because it enlists parents as partners with teachers. Parents help identify the problems to be tackled and they help devise the strategies to be used.

“Through this solution-focused partnership approach, relationships between parents and teachers are strengthened,” she said. “They both learn easy and effective strategies for managing student concerns and learn to work together as partners.”

Students maintained their improved performance for at least one year after participating in the program, she added, and parents formed stronger relationships with future teachers as well.

Another study of the approach now is underway at a number of schools in rural Nebraska.

The CBC approach has been under development and study since about 1990. It also has been tested in urban areas such as Philadelphia, Salt Lake City and Madison, Wis. Schools. The Center’s grant-supported research studies allow UNL-trained consultants to provide services free of charge.

To help educators incorporate CBC concepts into their work with parents, the center provided a training workshop for teachers and other professionals at a professional development conference at Educational Service Unit 6 in southeast Nebraska. It also has worked with an organization that serves children with autism spectrum disorder in Ontario, Canada. In June, Clarke will provide a training session as part of the Early Childhood Conference being held at Concordia University in Seward.

The idea of hiring a consultant to build family-school partnerships does not have to be daunting, even to financially strapped school districts, Clarke said.

“A lot of schools systems already have a person in a problem-solving role,” she said. “It may be the special education coordinator or some other specialist. Many schools have systems very similar to what we’re discussing. But one of the things we find time and time and time again, is that they need continued guidance and training at building successful partnerships.”