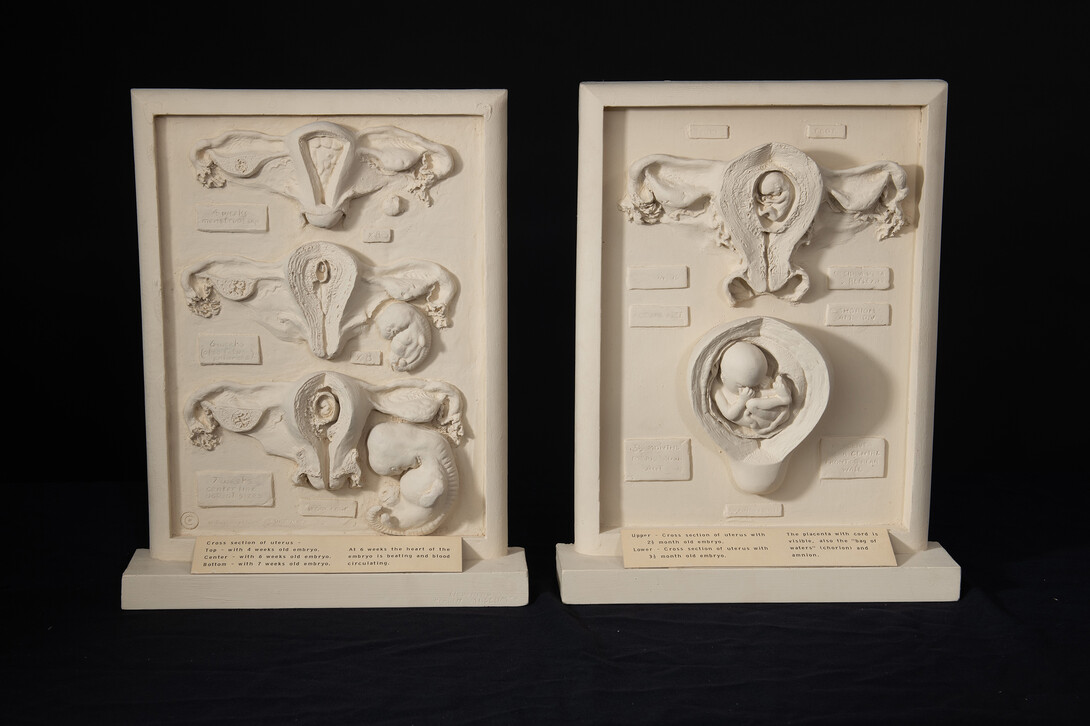

The Dickinson-Belskie Birth Series — a collection of 24 sculptures depicting human development in the womb — captured the public’s imagination at the 1939-1940 World’s Fair in New York City. Long lines formed as people marveled at their intricate detail and the awe they evoked.

But eventually the series, along with the doctor and artist who created them, receded from the historical record of medicine.

Eighty years later, through happenstance and the research of the University of Nebraska–Lincoln’s Rose Holz, the sculptures and their accompanying story are again grabbing attention.

Holz, associate director and professor of practice of Women’s and Gender Studies, first learned of the pioneering obstetrician-gynecologist, Dr. Robert L. Dickinson, during her graduate school years when she was writing her dissertation. Dickinson was an early advocate of prenatal care and family planning, and his Birth Series, which he developed with sculptor Abram Belskie, was meant to start a national conversation.

“The collection was intended to educate people about the process of pregnancy,” Holz said. “The organization that commissioned them (the Maternity Center Association) wanted to encourage women to get medical supervision as soon as they learned they were pregnant — and not wait until the moment the baby arrived, which was actually quite common back then. For most people, these sculptures were truly amazing because they offered a window into prenatal development, which was normally hidden inside a woman’s body.”

The series — which starts with a depiction of the female reproductive anatomy and traces the process of in utero development through delivery — was so popular that Dickinson and Belskie created a second set to reduce the long lines that had plagued the exhibit.

Following the fair, the sculptures went on display at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City and the offices of the Maternity Center Association.

“However, while the sculptures remained popular for a couple of decades, they then just sort of disappeared,” Holz said.

Doctor, artist, educator

The original set was based on drawings by Dickinson, himself a doctor and an artist. Belskie did most of the sculptural work. To capture further the process of in utero development, Dickinson and Belskie used thousands of X-rays taken of women throughout pregnancies, including during delivery, to design the sculptures. Admittedly, this would be ill-advised in medical circles today, but at the time, the risk was unknown.

The sculptures were effective at illustrating the process of embryonic/fetal development, so much so that they were recreated for hospitals, medical schools and museums. Dickinson also had the sculptures photographed and the photos were printed in a physically large volume, the “Birth Atlas,” which was purchased by doctors, universities, libraries and more.

“There was a high demand, but reproducing the sculptures themselves was not cost-effective. They were also cumbersome and fragile,” Holz said. “So Dickinson used photography to reproduce them in order that they could be more easily made and more widely available. The imagery in the “Birth Atlas” then became an important tool to educate the public and medical professionals about the process of pregnancy.”

Holz’s research uncovered that sculptural recreations were also commissioned for about a half dozen educational entities in the 1940s, including a public health museum in Cleveland, Ohio, where a Nebraska alumnus and benefactor saw them.

Ralph Mueller, inventor of the alligator clip and namesake of the university’s iconic Mueller Tower and Mueller Planetarium, purchased a set for his alma mater. The set debuted in 1952 as a feature in the University of Nebraska State Museum at Morrill Hall’s Ralph Mueller Public Health Gallery.

But again, like the other sets at places dotting the United States map, they disappeared in the 1970s.

What’s lost is found

In the early 2000s, it was lunch-time conversations at Maggie’s Cafe in the Haymarket with another historian of women, medicine, and sexuality (Sarah Rodriguez) that reinvigorated Holz’s interest in Dickinson.

“No matter where our conversations started, they always ended up about him,” Holz said.

Then Holz came across a copy of the “Birth Atlas” in the medical history library on East Campus.

“I started to see the pursuit and my colleague mentioned she thought Nebraska had a set of the Birth Series sculptures,” Holz said.

She reached out to the University of Nebraska State Museum at Morrill Hall to ask about the sculptures, but no one Holz contacted knew about them.

Holz kept researching Dickinson’s work, and she kept wondering. In 2014, she reached out to the museum again. She was put in touch with collection manager George Corner.

“He’s the resident historian, the oral historian there,” Holz said. “He had to dive into the museum storage in Nebraska Hall, but he found them. I was just over the moon. I went with my husband and a friend to see them, and we took a bunch of photographs.”

Holz has since published a scholarly article and a book chapter about Dickinson and the Birth Series. She’s also given about a dozen talks on their history — including one in Boston, where she met descendants of Dickinson.

“That was funny, because it was another one of those odd moments, where this stuff just fell into my lap,” she said. “I was at my computer and I get these two emails from his granddaughter and great-granddaughter, and they found out I was giving a talk in Boston.

“When I gave the talk, half the audience were Dickinson’s descendants.”

While Holz has moved on in her work, she can’t quite seem to walk away from the sculptures, and she thinks there’s something more to the sequence of events that brought the art to Nebraska, and to her.

“It’s been so weird and serendipitous, I really think it’s Dickinson, even though he’s been dead for almost seventy years,” Holz said. “Every time I think I’m out of ideas or I’m ready to move on, someone new reaches out to me and then I think, ‘well, maybe I’m not done with this.’ They’ve taken on a life of their own.

“I think Dickinson thinks he hasn’t gotten the recognition he deserves. And here I am, doing some research and I stumble on one of the few existing sets of the Birth Series left. I’ve talked with archivists and historians about them. As far as I can tell, of the two original sets made for the 1939-1940 World’s Fair in NYC, remnants of one are buried in storage at the American Museum of Natural History while the other likely ended up in the landfill. I know of only two other places that still have them — the Warren Anatomical Museum in Boston, which serves Harvard Medical School, and the Belskie Museum of Art and Science in Closter, New Jersey.”

Holz said she no longer travels with the sculptures, as they are precious and rare. She hopes that the University of Nebraska State Museum will include them in future exhibits, but she’s still ready to share their story and keep Dickinson’s name among the pioneers of medicine.