For the better — or worse — part of a year, Amelia-Marie Altstadt was mostly alone with their cats and their thesis.

It wasn’t exactly what the personable, extroverted local of Coronado, California, had envisioned when they joined the graduate program in educational administration at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln in fall 2019. But thanks to more than a little help from a network of supporters, and an intrepid decision inspired by a lifelong love of theater, Altstadt is set to join the newest ranks of Husker alumni.

Long before they did, family ties had kept Altstadt tethered to the Cornhusker State. Recollections of a 7-year-old Amelia-Marie visiting cousins in Nebraska for the Fourth of July, igniting fireworks that the wildfire-scarred California could not risk, had lingered in their memory. One of those cousins had graduated from Nebraska and was a Lincolnite working at Hudl. Altstadt’s late paternal grandfather, Bill, was also a Husker before joining the Air Force and leading the family to Greater San Diego.

Still, Coronado is a military town whose beaches are drenched in sunshine and the idyllic waves of San Diego Bay. So when Altstadt ventured the idea of attending Nebraska U, their mother put them on a Nebraska-bound flight in March 2018 with a challenge: “Go see if you can handle the cold.”

Altstadt found that they could. Just as importantly, they found that “everybody was just so willing to help.” When they did apply to the program, but forgot to attach a resume, the program coordinator was quick to gently let them know.

“That was a level of care that maybe you don’t see in a lot of other places,” Altstadt said. And after learning that they’d have an assistantship working with the Nebraska College Preparatory Academy, which mentors and offers full scholarships to low-income, first-generation students, Altstadt was all in.

In their first semester, the self-described “musical theater nerd” acted in a local production. The show might have taxed more of their time than anticipated, but it was a way of building a community of friends in a new city, and it was working. Altstadt was also formulating the core of a thesis that, unbeknownst at the time, would eventually integrate that zeal for the theater.

Altstadt had decided the thesis would share the little-told experiences and perspectives of a child of disabled adults — specifically, their own. Altstadt’s mother and father, who met at the 1984 World Series, use wheelchairs. Though disabled American parents number in the millions, Altstadt’s search for research that conveyed the unique difficulties, delights and considerations of her childhood, or even some semblance of it, had turned up almost nothing.

Altstadt wanted to begin sketching and coloring in that missing picture. They wanted people to know, for instance, what it was like to contend with the forced intimacy of non-disabled people — sometimes total strangers — expecting the disabled or their families to share the deeply personal in ways not asked of the non-disabled.

“People would constantly ask me very inappropriate questions growing up,” they said. “‘How do your parents have sex?’ Or, ‘Are you adopted?’ This is all before even, ‘Hi, how are you? What’s your name?’”

Then came March 2020, the pandemic, and months of physical isolation that would have challenged the sociable Altstadt even had they not been embarking on such a daunting project.

“Living alone, having to be self-motivated (while) writing a thesis,” they said, “it was not the best confluence of events.”

They turned, via Zoom and phone calls, to the people they could trust and rely on. Family back in California, who knew Altstadt best and could offer the familiarity of home. The 15 members of the graduate program cohort who, in trying to maintain their balance on the same shifting ground Altstadt was, could empathize and commiserate with each other.

“The coolest thing about my cohort was, if somebody was busy one weekend, and they were part of a group project: ‘OK, cool. We’ll do some more of this. You’ll get us next time.’ Because everybody has things going on,” Altstadt said. “It’s supposed to be uplifting. It’s supposed to be community. And I think Nebraska does a pretty great job at that, and the educational administration department does a really good job of fostering that. We felt really empowered in a lot of ways, through all of the struggles and all of the joys.”

One of those struggles arrived when Altstadt realized, then shared with thesis adviser Stephanie Bondi, that the first rendition of the findings chapter wasn’t addressing the research questions Altstadt had posed. The thought of rewriting the chapter, especially given her ADHD, was an imposing one. But another thought — one that might allow her to combine the academic with the aesthetic, the traditional with the playful, her lived experience with her passion — was renewing her excitement.

“I always had it in my mind that if I had extra time, I would write my findings as a play,” they said.

Altstadt pitched the idea, as a young playwright might a script, to Bondi, who encouraged them to pursue it. Inspired by musicals like “Fun Home” and plays like “The Vagina Monologues,” Altstadt began writing “Up the 5,” a seven-scene dramatization of taking a college tour road trip with family from Greater San Diego, where she was raised, to Sonoma County, where she earned her bachelor’s degree.

At various stops along the drive, three versions of Amelia-Marie — young, teen and adult — relay their actual experiences as a child of disabled adults, each sharing their related but age-specific feelings on those experiences.

My world was shaped by wheels, adult Amelia-Marie says of growing up in a home adapted for her parents. When I started going into the world, that was when I realized that the world was built to be different, she continues, watching as her younger self and her mother enter the scene. I didn’t understand why that was the case. It was clear to me that my world was better with my momma in it alongside me.

The chapter is replete with scene descriptions of three sets that represent varying levels of accessibility Altstadt’s family would encounter: environments clearly designed for full wheelchair access, those notably less but still ultimately accessible, and those entirely inaccessible to wheelchair users.

But as Altstadt knew, access is about more than physical space.

“A lot of people hear ‘research’ and think, ‘I don’t want to read that,’” they said. “And it’s not very accessible to people who have not developed the skills to read research. But a play, if it’s performed or read, is accessible.

“I also think the change infused the fun and the interest back into my thesis. This is a subject that I love and think is really important, but during a pandemic, with a self-led project, trying to graduate school, not seeing anybody — that’s just difficult. This new idea made it fun again. And this approach helped me express what I wanted to express.”

Altstadt adopted a similar approach with the discussion chapter. Taking after the form of a theater talkback — a post-performance conversation between cast and audience — Altstadt rendered the chapter as a Q&A in which the Amelia-Maries answer questions from researchers and professionals working in student affairs.

“The thing that I love about theater the most is how much you can learn from it, and how much interaction there really is between an audience and the performers,” they said. “That’s what I wanted to bring into this, because the data isn’t lifeless — my experiences are the data. Presenting my thesis in this format allowed me to show rather than just tell.”

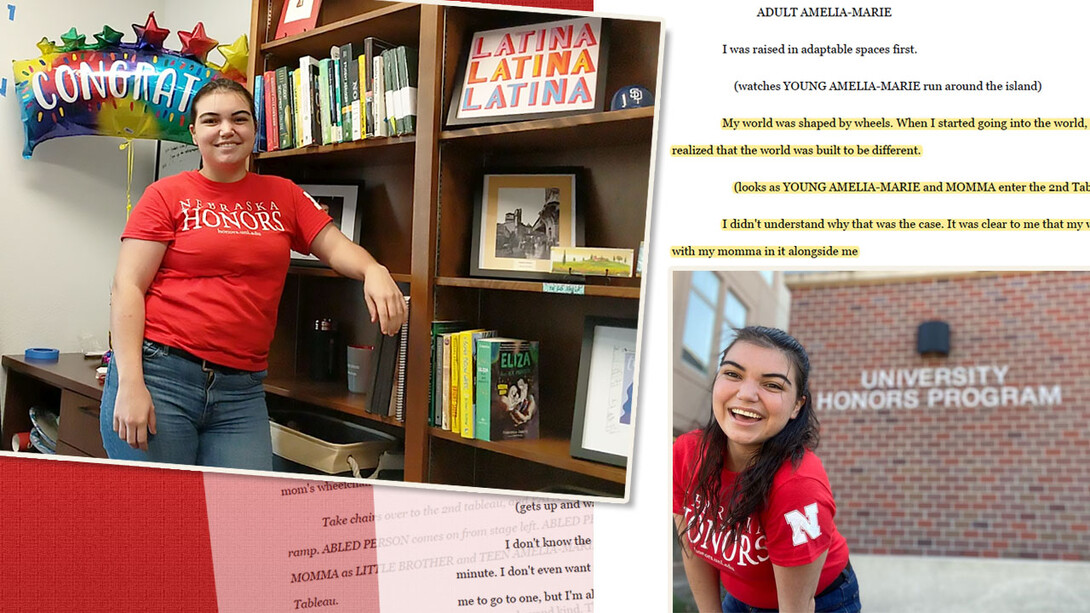

Ahead of wrapping the thesis and graduating with her master’s this August, Altstadt landed a job as the coordinator for the University Honors Program. The position entails everything and anything that Honors has to offer: “recruitment, retention, events, advising and any fresh ideas coming around the bend from our director, Dr. Patrice McMahon,” they said.

Altstadt is full of ideas, too: They proposed and will teach a new experiential learning course that prepares Honors students for National Novel Writing Month, which challenges people to write 50,000 words — about 1,667 per day — between the start and end of November.

And when November does roll around? Altstadt said they’ll gladly prove again, as they first did back in 2018, that a Southern Californian turned Nebraskan can handle the cold.

“I’m looking forward to continuing to work here and be in Lincoln. That’s maybe surprising to people when they hear that I’m from San Diego. I do miss the ocean, and I could do with less humidity,” they said with a smile. “But I love it here, and I love working with students. That’s really all that I need.”