Many Nebraskans have visited Pershing Auditorium in Lincoln for sporting events and concerts. The building is named after World War I Gen. John J. Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Forces in Europe.

In 1917, Pershing helped transform America’s peacetime military of 220,000 soldiers and officers. Within 18 months, Pershing and 2 million American doughboys were fighting in France. They helped the Allies turn the WWI battle tide against German troops and force a surrender.

Stern and ramrod straight, Pershing wasn’t simply a general. He was the highest-ranking active duty officer in American military history and once one of the most well-known men on earth.

“I would say his bearing. His presence,” said Doran Cart, curator at the National WWI Museum and Memorial. “You see it in everything. You see it in the photographs. You see it in the film footage.”

Today, Pershing’s name is recognized by few Americans, even in Nebraska where an important part of Pershing’s life unfolded.

Before Pershing arrived at the University of Nebraska, he served in New Mexico with the U.S. Army’s 6th Cavalry. The young lieutenant and his troops helped protect settlers and keep peace with the Apaches, Zunis and the Navajo who lived in the canyons and rugged mountains of the desert southwest.

In his memoirs, Pershing wrote sympathetically of Native Americans. He had seen them forced from their land, robbed and murdered by some white men.

“It is small wonder that the Indian frequently went on the warpath. It then became the duty of the army to punish him, yet the soldiers cherished a sincere sympathy for him and detested those who exploited and mistreated him,” Pershing wrote.

After five years on the American frontier, Pershing grew conflicted over his military career. No wars loomed on the promotional horizon and Pershing pondered practicing law.

“He does get a chance to take a break. To go back to a place where people don’t act and think and look like he does. You know, a college campus,” said Richard S. Faulkner, a military historian at the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas.

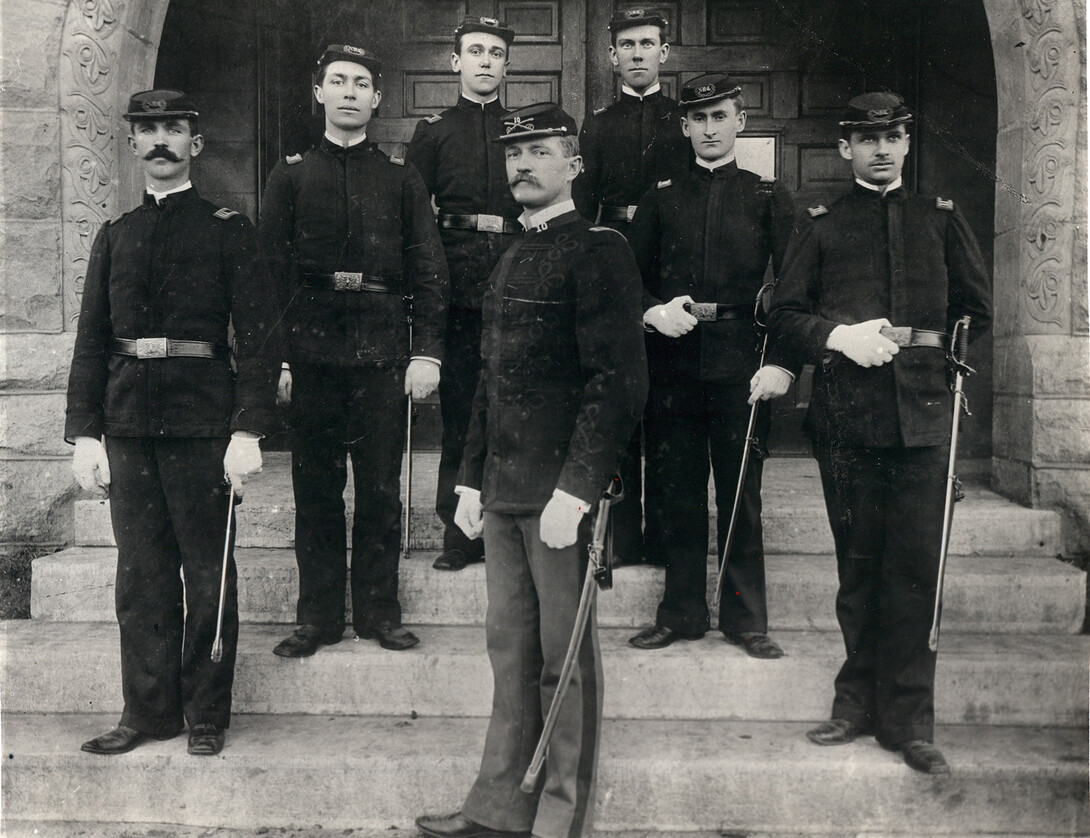

Pershing was reassigned to the University of Nebraska in 1891. He led the cadet training program, taught classes and studied law.

York College history professor Tim McNeese said when Pershing arrived at the university its cadet training program had dwindled to just 90 students.

“Students didn’t take it seriously,” McNeese said. “Faculty couldn’t care less. The administration was kind of, ‘This is something we have to do.’”

It didn’t take long for Pershing to instill discipline and pride, insisting coats be buttoned up and shoes shined.

“All of these farm boys were kind of, ‘Wait, wait, wait. Who’s this guy and what?’” McNeese said. “But, they take to it and they take to him.”

Within a year, Pershing’s university cadet corps swelled to 350 students.

In 1892 Pershing’s cadets were put to the test at a national military drill competition in Omaha. The packed crowd included governors from several states, including Nebraska.

The night before the competition, Pershing wasn’t satisfied his cadets were taking the competition seriously. He assembled his men and told them he thought they were terrible.

The next morning, as a glum University of Nebraska cadet corps team reached the Omaha parade grounds, Pershing stepped sternly in front of his men and said: “I think you’re going to win first place.”

Years later, Pershing confessed why he berated his cadets.

“They were too good. They were perfect, and they knew it,” Pershing said. “I couldn’t let them go into a competition like that.”

When it was announced Pershing’s Nebraska cadets had won the maiden division in the national drill competition, hundreds of students and faculty climbed over the drill field fence and charged the field to celebrate.

“Even the chancellor of the university, Chancellor Canfield, who is not a small man, was climbing over this 8-foot tall fence,” McNeese said.

At that moment, McNeese said a lot of civilians, including well-educated people and presidents of universities, began taking notice of Pershing.

As a teacher, Pershing had interesting moments at the university too.

Historian Gene Smith wrote that Pershing taught math class every school day for three hours “with as much success as he had with his cadets” remarked Chancellor Canfield. Interestingly, the chancellor’s daughter and future writer, Dorothy Canfield, said Pershing taught math more like a military general than a professor.

In 1895, Pershing’s time at the university came to an end. With a law degree in hand and fueled by the many friendships he formed in Lincoln, Pershing recommitted himself to the military and what would be a historic career.

After WWI, Pershing remained a frequent visitor to Lincoln. He called it his second home and traveled here frequently from Washington, D.C. to visit his two sisters. They lived for decades in a home Pershing owned near 17th and B streets. Pershing’s son Warren also lived with his aunts in Lincoln during WWI as his father commanded U.S. troops in Europe.

In honor of their former cadet corps commander, the University of Nebraska military drill team renamed itself “Pershing’s Rifles.” Today units like them still flourish across the country. They are known as the National Society of Pershing Rifles — a lasting tribute and legacy for Pershing 127 years after he first arrived at the University of Nebraska.