Mysteries are stitched into the collections of the International Quilt Museum, and a group of volunteers is working to decipher them.

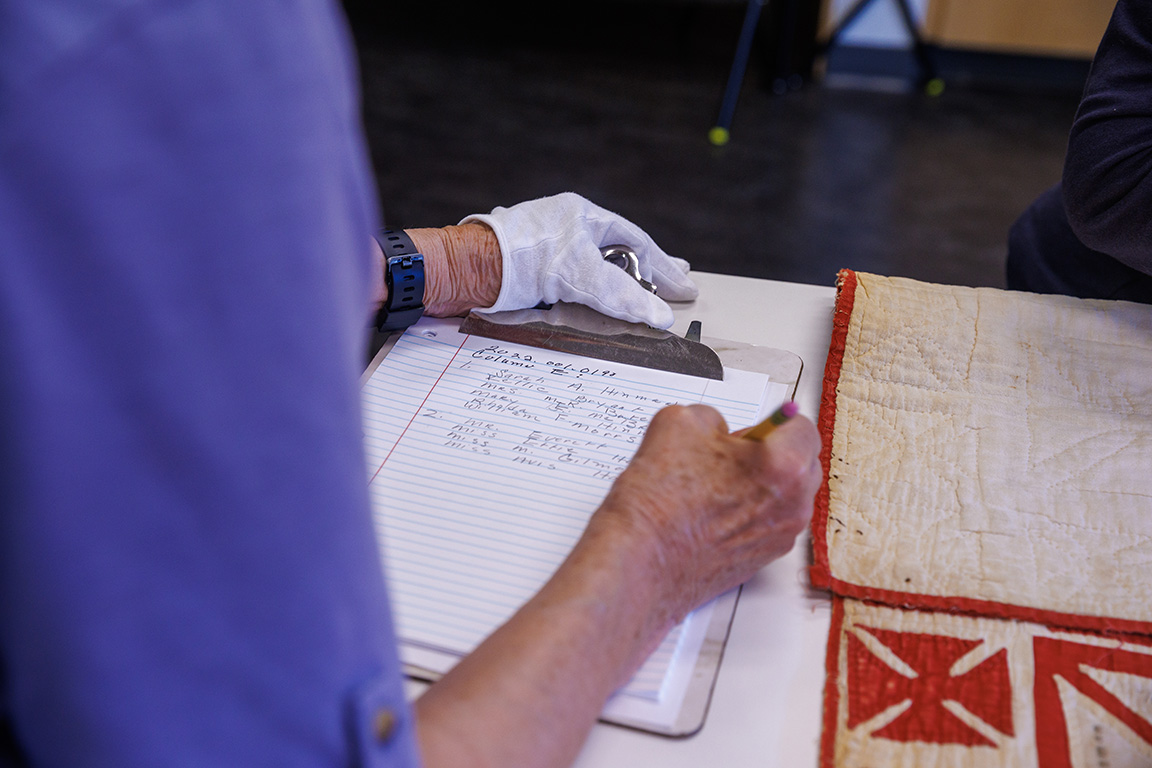

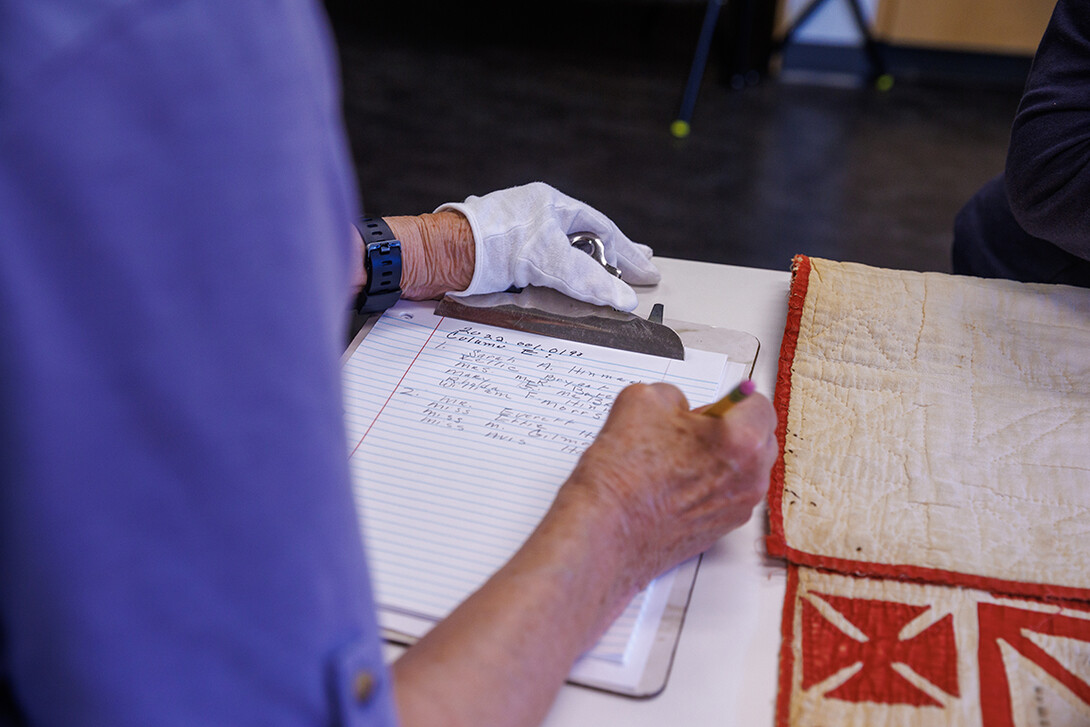

The Genealogical Task Force devotes time to investigating inscribed pieces that come into the museum’s possession and uncover the history hidden in the fabric. Through their research, they are able to learn more about each quilt.

“It’s good if you can tell people that story,” said Susan Macy, task force member.

The Genealogical Task Force researches any quilt that comes in with names written or embroidered on it. They go through each quilt block in a grid and record the names and other available information to research through sites like Ancestry, Find A Grave and United States Census records. The information they gather is then added to the quilt’s entry on the museum’s database. The group has researched more than 600 quilts in the 20 years it has existed.

Sometimes the biggest challenge is simply reading the names. As handwriting changes over the years or embroidery skills vary, names can become more difficult to transcribe.

“Old signatures all have the fancy curlicues and stuff, and we can’t tell one letter from the other sometimes,” said Carolyn Kitterer, task force member.

More background about when or where the quilt was made can be helpful, but in some cases they have to go on names alone. This can make it difficult to use census records because census workers often record names as they sounded, a process that results in spelling differences. They look for names that are more unusual to see if that leads to more connections.

“You just try to find some names that are maybe a little unique,” Macy said. “It’s fun. It’s a guessing game. It’s a puzzle.”

Most of the inscribed quilts were made for church and other fundraisers, when people would give a small donation to be able to write their name on the quilt.

“They were making money for the war, supplies for soldiers, church raffles, or they might be made for a pastor who was leaving,” Macy said.

Others might have been given as a gift for a wedding or birth of a child or made as a memorial. Loved ones would write their names and sometimes a message as a commemoration.

“They would write a prayer or a poem about what the person meant to them,” Kathy Aiken, task force member, said.

Carolyn Ducey, Ardis B. James curator of collections, said because so many of the quilts were made by women, the research helps to tell stories that often went untold.

“Through their documentation, which we regularly share with researchers, we have a more accurate and nuanced knowledge of the women who made quilts,” she said. “This is especially important, as women's lives were not typically recorded or acknowledged. The makers live on through their quilts and the information we learn.”

In lucky cases, members of the group are able to connect with people who worked on the quilt or their relatives, who can tell them more about the story. The task force does not transport the quilts out of the museum, but may take photos to show the family.

A quilt made in 1928 even sent Macy to Canada, where she spoke to members of the Forest United Church in Ontario. A church member remembered giving a nickel and writing her name on it as a little girl.

Macy also discovered that another name on that quilt was that of a woman who lived in Lincoln and was a former member of the university’s agronomy faculty. The woman was able to find her name and that of her mother and a brother who had died in World War II.

And once, she visited a family in Kansas near where she grew up because Macy had recognized a name from the family on one of the museum’s quilts.

Sometimes people will learn of the quilt and come to visit. Macy had the opportunity to show a family from a Mennonite community in Kansas two baby quilts made for members of their family. While on cross-country road trip, they stopped and were able to see the actual quilts.

“One of the brothers spoke up and said, ‘This is a good place for them,’” Macy said.

She said any chance to bring together people and the work is a special way to find answers to the questions any of the quilts raise.

“It means a lot to them and it’s fun for me,” Macy said. “All of a sudden you found one of those missing pieces.”

Share

News Release Contact(s)

Tags

High Resolution Photos

HIGH RESOLUTION PHOTOS

HIGH RESOLUTION PHOTOS