Welcome to Pocket Science: a glimpse at recent research from Husker scientists and engineers. For those who want to quickly learn the “What,” “So what” and “Now what” of Husker research.

What?

To reduce sexual assaults on university and college campuses, many U.S. institutions have begun adopting policies based in what’s known as affirmative consent. Under past definitions, sexual assault occurred when a perpetrator ignored a verbal rejection of a sexual advance — a standard commonly referred to as “no means no.” By contrast, the affirmative standard asserts that consent can be inferred only from a conscious, clear, voluntary “yes” throughout sex — that “yes means yes,” and that the absence of a “no” does not equal consent.

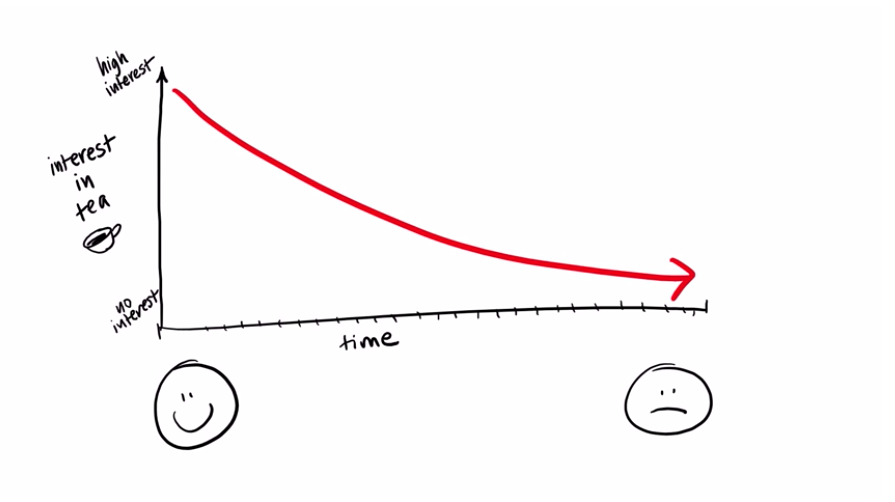

Universities and colleges often explain affirmative consent by defining it in writing. Some institutions have supplemented those written definitions with a popular YouTube video that describes affirmative consent through the metaphor of tea: what it means (and doesn’t mean) to accept or decline a cup under various conditions relevant to sexual interactions. Few studies, though, have examined whether those messages actually inform perceptions of consent and assault — and whether one form of messaging might prove more effective than another.

So what?

When compared with those who received no information on affirmative consent, participants who watched the video were more likely to correctly perceive the physical assault as one. Those who read the definition of consent, meanwhile, perceived the physical assault about the same as the control group did. Surprisingly, participants who read the definition were also more liable to misclassify consensual sex as assault, hinting that the written standard might confuse the issue for some.

Neither the written nor video explanation appeared to influence perceptions of assault or consent in the context of verbal coercion, with both groups just as likely as the control to misclassify that scenario as consensual sex.

Now what?

Overall, the findings suggest that institutions might benefit from integrating metaphor-fortified video when educating students and employees about affirmative consent, the team said. Further research could help hone those metaphors to refine understanding of verbal coercion, the researchers said, and counteract rape myths still embedded in U.S. society.