Political partisans would like you to believe voters’ heads will explode if faced with candidates crossing party lines on key policies – a Democrat who opposes abortion, say, or a Republican who supports gun control.

In a new study, University of Nebraska-Lincoln researchers found that self-identified liberals were more likely to notice when candidates deviated from the party line. Liberals also tended to take longer to react to inconsistent positions from Democrats. And in the majority of instances, they evaluated those inconsistent positions as “bad.”

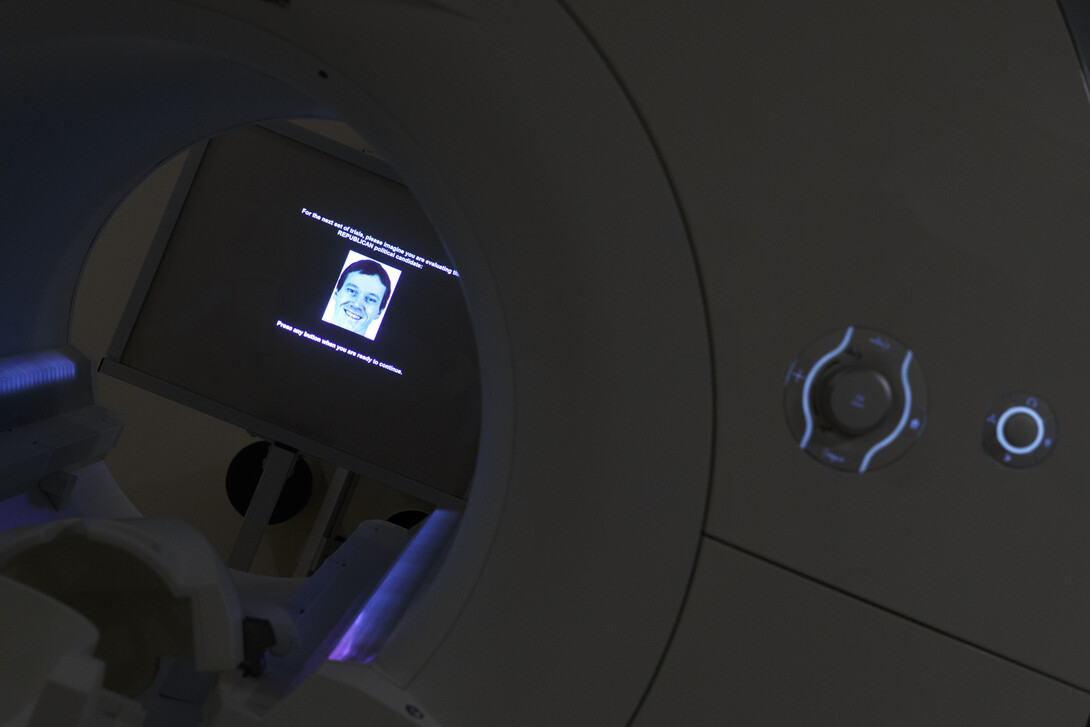

The study used a powerful functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging machine at the university’s Center for Brain, Biology and Behavior to observe what happens inside the brain when people are faced with “incongruent” policy positions from their party’s candidates. The researchers used the scanner to see if certain areas of the brain activate when people evaluate candidates’ stances on a range of issues.

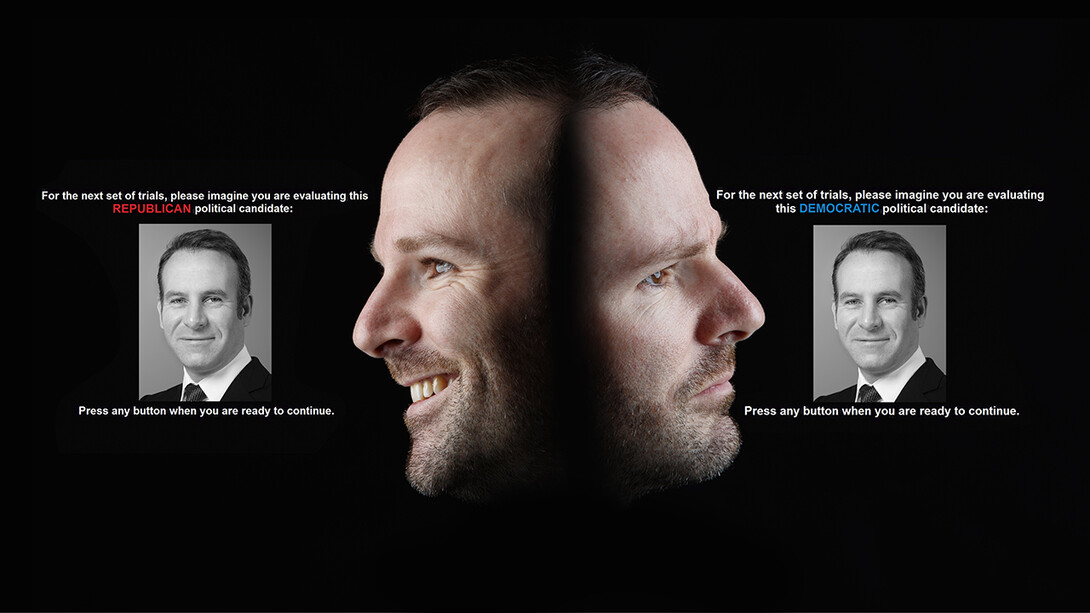

Participants were asked to review made-up candidates’ positions on dozens of issues, then decide within milliseconds whether those positions were “good” or “bad.”

“We found that liberal and conservative participants processed the information differently and that liberals were more likely to penalize candidates who expressed incongruent positions,” said lead researcher Ingrid Haas, a political psychologist at Nebraska.

That may mean Democratic candidates with conservative leanings may have a trickier time in today’s political climate than Republican candidates with a liberal bent, Haas said.

The findings have implications for the causes of political gridlock, she said. It may not be true that polarization comes only from the top, with politically polarized elites alienating constituents by refusing to compromise. The study hints that polarization may also emerge at the grassroots level.

Despite conservatives’ reputation for being less tolerant of ambiguity, the findings suggest liberals are more likely to scrutinize inconsistency, Haas said.

“If less scrutiny is applied to Republicans for policy deviations, it may indicate that specific liberal causes and policies have some electoral viability among Republican candidates,” Haas and co-authors wrote in the study.

There are other possible explanations for the differences in conservative and liberal reactions: Perhaps the GOP has become so fractured on issues like health insurance, social issues and foreign policy, the researchers suggested, that voters don’t always recognize when a candidate has left the ideological fold.

Haas’ research team included Melissa Baker, a former Nebraska student and now a graduate student at the University of California at Merced; and Frank Gonzalez, a former Nebraska graduate student who is an assistant professor at the University of Arizona.

The Center for Brain, Biology and Behavior, or CB3, is an interdisciplinary center at Nebraska that brings together faculty in the social, biological and behavioral sciences and engineering. The center’s state-of-the-art facilities and multidisciplinary environment expands understanding of brain function and its effects on human behavior. The center’s unique capabilities and partnership with Nebraska Athletics deepen the university’s research capacity, including its leading expertise in concussion research.

The team conducted brain scans of 58 adults while they reviewed policy positions of four hypothetical political candidates – two Democrats and two Republicans. While in the scanner, participants saw stock photos representing the candidates and responded to about 50 of their policy positions on issues such as the death penalty, teaching evolution, immigration, same-sex marriage, climate change and gun control.

About one-third of the time, the hypothetical candidates held positions that conflicted with their party’s. Participants pressed a button to indicate whether they felt “good” or “bad” about the candidate based on the policy stance.

Conservatives were less likely to notice whether policy positions followed party lines. They also showed a stronger positive response when Democrats held conservative positions. They were more evenly divided in ruling whether it was good or bad when a candidate deviated from the party platform.

Researchers found that the areas of the brain used to monitor conflict and evaluate information were more active on incongruent trials for liberal participants compared to conservative participants, especially when they evaluated “in-group,” or same-party, candidates.

“These findings may be concerning to those who see political polarization as a problem as well as to those who desire meaningful social change as they demonstrate the psychological process that help to hinder the likelihood of political compromise, which is necessary for translating desired policy into implemented policy given the divided nature of government in the United States,” the authors concluded.

The study was published online in the journal Social Justice Research.