Innovative research by University of Nebraska–Lincoln scientists studying the reproductive biology of cows offers significant long-term potential to address infertility challenges for women.

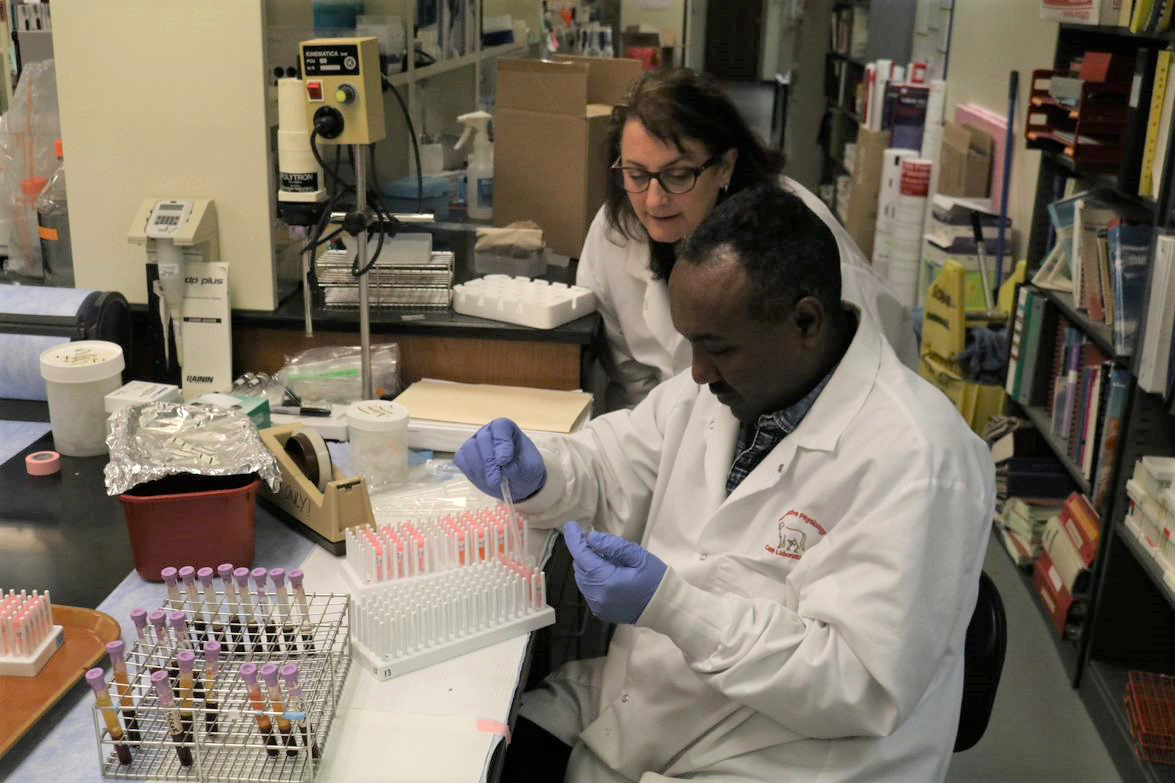

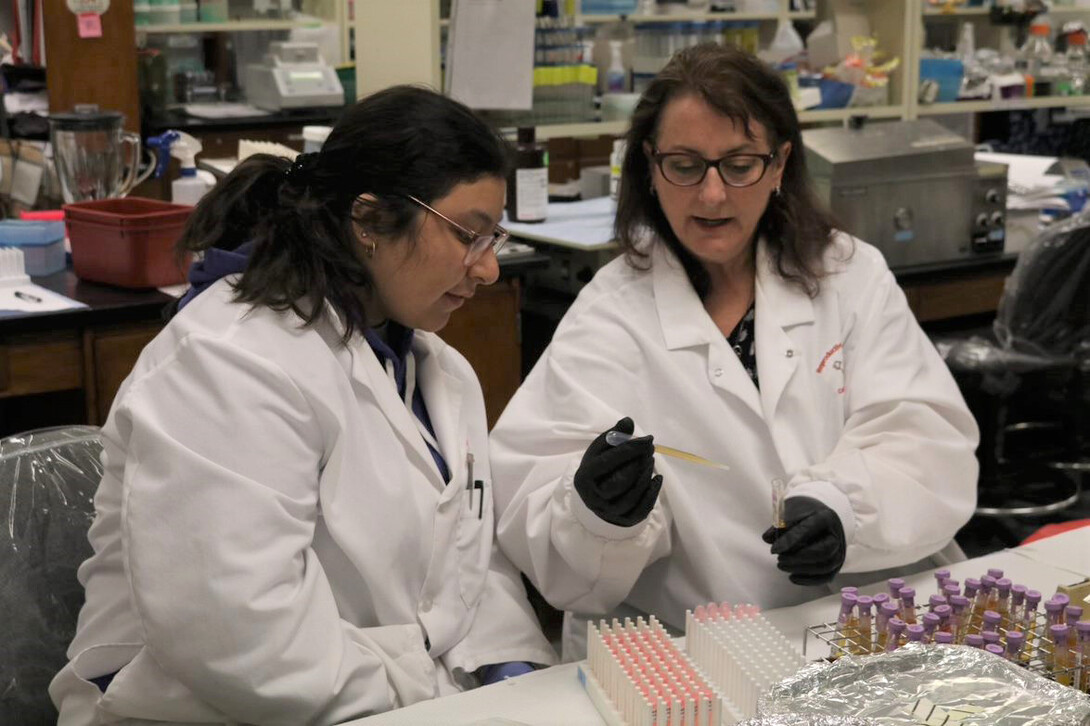

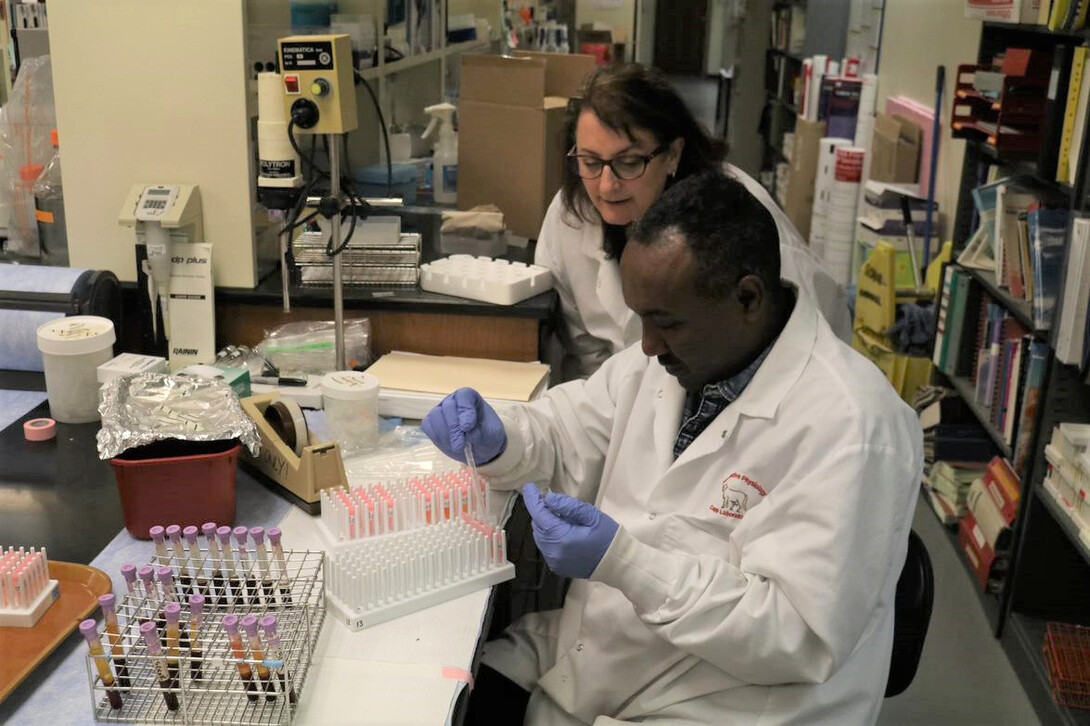

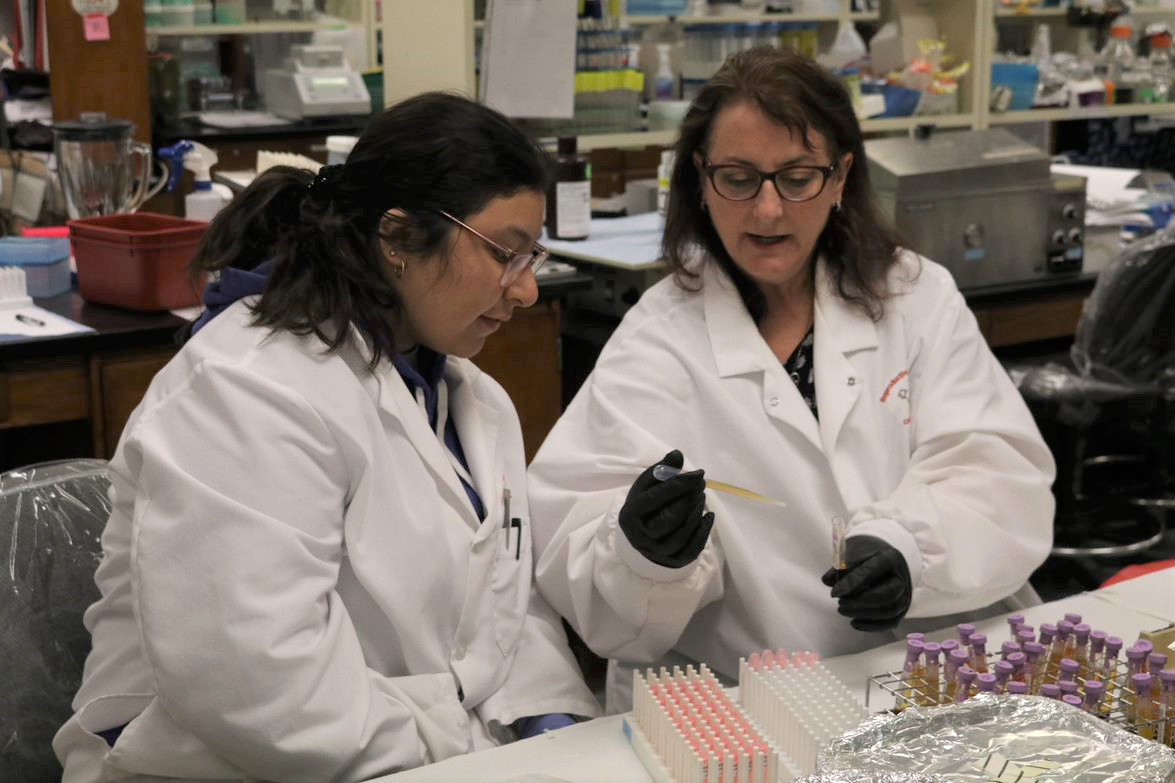

Reproductive physiologist Andrea Cupp and colleagues in the Department of Animal Science are deepening the understanding of bovine reproductive biology by using advanced genetic analysis, culture of reproductive tissue and other tools.

That basic research can have significant applicability in understanding human infertility challenges, due to the many general parallels in the reproductive biology of cows and women, said Cupp, the Irvin T. and Wanda R. Omtvedt Professor of Animal Science.

“Cows ovulate one egg every reproductive cycle,” Cupp said. “The gestational length — the time of incubation of a fetus — is similar: nine months. Cows have a similar reproductive cycle, similar endocrine hormones, and the size of the ovary is similar. It’s directly applicable to female human conditions.”

Livestock face significant problems with infertility, Cupp said. An example is anovulation, the lack of release or the irregular release of an egg from the ovary during the reproductive cycle.

“Cows have a lot of problems with anovulation, as do a lot of other species, including humans,” said Cupp, who earned her master’s and doctoral degrees from Nebraska.

Cupp and her colleagues have found an additional parallel: A significant percentage of cows studied by the Husker scientists have symptoms similar to those experienced by women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), one of the most common infertility conditions in the United States. PCOS affects between 6% and 11% of American women of reproductive age.

Irregular reproductive cycles are one of three central symptoms associated with PCOS. A second factor is an excess of androgen hormones. The third factor: The ovary’s follicles, each containing an immature egg, fail to develop, in a condition called “follicular arrest.”

Cupp found that the herd in her study stood out for the strikingly high levels of androgen among many of the cows, similar to the condition of women with PCOS. She also found that a significant percentage of heifers reached puberty prematurely, while a notable percentage developed quite late. Those are also common conditions for many women with PCOS.

The findings marked the cows as a good model for infertility research in women. Her Husker colleagues, Cupp said, are contributing in major ways to the range of this study.

Jennifer Wood, professor in molecular and cellular reproductive biology, studied PCOS as a postdoctoral fellow and has been a major collaborator on the project. Bob Cushman, a research physiologist at the U.S. Meat Animal Research Center in Clay Center, Nebraska, has been helpful in developing techniques to obtain ovarian tissue for study. To help with understanding the genetic impact, several scientists have contributed: Jessica Peterson, associate professor in animal functional genomics; Matt Spangler, professor and beef genetics specialist; and Melanie Hess, quantitative geneticist and research assistant professor.

Recently, Ligia Prezotto, a neuroendocrinologist and research assistant professor, has joined the team to study how a mother’s exposure to increased hormones during pregnancy may wire the brain differently in the fetus and contribute to PCOS-like symptoms.

Scientific research to address female health, including fertility, has long faced major obstacles because the study of disorders and many biological systems has traditionally used male animal models instead of female ones.

It is more difficult to study female physiological processes because of the complications created by the female reproductive cycle. Yet, those hormonal differences during the menstrual cycle in women and reproductive cycle in female livestock are critical to their health and response to disease, warranting detailed scientific understanding.

Women “are very understudied as a gender, whether humans or animal models” when it comes to research, Cupp said.

Cupp’s research focuses in particular on factors with the potential to restore proper blood vessel formation in ovaries, which can promote healthy development of ovarian follicles that contain the egg. A key focus is vascular endothelial growth factor, a protein that guides cellular signals for a variety of important blood vessel actions.

Her graduate students have used the growth factor to treat pieces of bovine ovaries, to see if the protein can promote healthy follicle development. Through that innovative lab approach, “we basically rescued those follicles and those ovary pieces from our high-androgen cows,” she said.

“We’re genotyping the herd,” Cupp said, “and sequencing their DNA to see if we can figure out what is contributing to the genetic variation in the herd, and we hope to tie that back to their pubertal or reproductive characteristics.”

Cupp pointed to important mentoring and support she has received from John Davis, professor and director of the Nebraska Center for Women’s Health Research at the University of Nebraska Medical Center.

PCOS has long been difficult to fully understand medically because it’s affected by a wide range of factors, including genetics and environment. Ultimately, Cupp said, researchers will need to look comprehensibly at findings for the breadth of populations studied, animal and human.

A key guidepost, she said, is for researchers to avoid rigid assumptions.

“As scientists, we have to observe things, we have keep our minds open,” she said. “We have to follow what the data is telling us.”

Share

News Release Contact(s)

Related Links

Tags

High Resolution Photos

HIGH RESOLUTION PHOTOS

HIGH RESOLUTION PHOTOS