On a sweltering day at the Reller Prairie Field Station, Zoe Durand, Tori Markwell and Sophia Huss were toiling under the summer sun, meticulously unearthing skeletal remains.

Using brushes, bamboo skewers and trowels, the University of Nebraska–Lincoln students were carefully exposing bones, a tattered tan acrylic sweater and some gauzy fabric in a shallow grave. As they dug in, they preserved and bagged evidence, kept logs and took photographs. Nearby, another group of students labored over an additional shallow grave, exposing a skeleton still wearing athletic shoes. It was the first forensic excavation the students. The skeletons weren’t real, but the skills they learned very much are.

The process for excavations is comprised of a series of exacting, repetitive tasks, and 10 students from a variety of majors spent the first three-week summer session receiving hands-on training in these skills through the School of Global Integrative Studies’ class “Introduction to Field Work: Archaeology Field School.”

Ella Axelrod, an incoming graduate student in geography with extensive archaeological field experience, served as a teaching assistant for the class, which covered techniques for both forensic and archaeological excavations. She said the faux graves were designed to mimic a real-life crime scene where the expertise of forensic anthropologists would be needed.

“Within three weeks, we want the students to have these field techniques down, from surveying to excavating to filling out reports,” Axelrod said. “From the get-go, they’re working the scene. It’s a fast-paced field techniques course.”

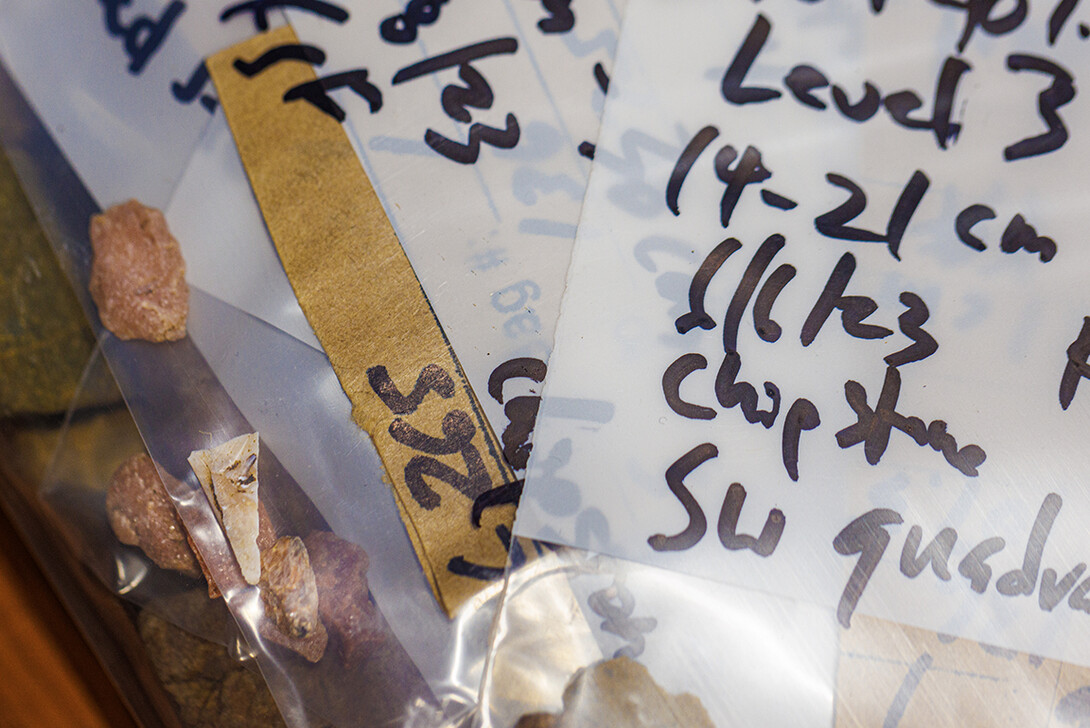

Up the hill, about a football field’s length away, three groups of students worked on archaeological excavations in 50-by-50-centimeter squares, sifting through the dirt from each five-centimeter-deep layer they had dug. They were looking for remnants of ancient civilizations — fire crack rock, pre-Colombian ceramics or chipped stone from the work of making tools and projectiles — and adding to the knowledge of this area from previous field schools. To keep accurate records, the students took measurements and mapped their finds as they collected them. Later, the artifacts were washed, bagged and cataloged.

“All along, the students are taking documentation, so they’ve got notebooks that are thick with descriptions at this point, which will be turned into reports,” said LuAnn Wandsnider, professor of anthropology and associate director of SGIS.

Wandsnider designed and led the field school — introducing students to pedestrian survey, reading and making maps, identifying artifacts, using GPS and other mapping equipment. She oversaw the archaeological dig, while Axelrod managed the forensics excavations. Offering both provided opportunities for students interested in forensics, archaeology, anthropology and geography.

While the goals for forensic and conventional archaeology are slightly different, most of the techniques are the same.

“Ella has complementary experience to what I have, and she really knows how to work the forensic kinds of situations,” Wandsnider said. “That really allowed us to fine-tune the experiences the students wanted to have.”

Students spent seven hours each day at Reller over three weeks. The renovations and cleanup at the Reller Prairie Field Station have made it possible for more students interested in archaeology and anthropology to gain on-site experience in excavation nearby, rather than needing to travel long distances, which can be costly.

“It’s just a lot cheaper than most of the field schools — a lot of them are abroad,” Zach Schenk, a senior majoring in English and anthropology, said. “This is a really good opportunity to get to do this at a place that’s nearby. It’s attainable.

“I’ve learned a ton while I’ve been out here, so it was super helpful, and I’ve met a lot of really cool people in the school, as well.”

Wandsnider said giving students an opportunity to attend a field school in anthropology and archaeology is important, especially as more and more jobs are expected to come open needing these skill sets.

“You really need to, especially with excavation, work at it awhile and develop some of that muscle memory and you need a longer stretch of time, which a field school provides,” she said. “There are tons of employment possibilities out there for people with these skills. Any time a road is refurbished or energy construction is done, they need archaeological work done. I’ve seen estimates that 8,000 positions are unfilled at this point, and it will become more important as more projects get approved under the recently passed Infrastructure bill.”

Wandsnider said having access to Reller Prairie also allowed SGIS to make a field experience part of the graduation requirements, beginning with the 2023-24 catalog.

“We previously only had it listed as general research methods experience, but now we’ve broken it down to field and laboratory experience,” she said. “We decided it was important to have both because that’s going to make our graduates more marketable in their future careers.”