In the decade since the U.S. government shut down funding of its largest high-level nuclear waste disposal site, America’s nuclear power plants have been without a designated facility to store the hottest, most radioactive spent fuels.

With a three-year, $800,000 grant from the U.S. Department of Energy and looking many millennia into the future, a research team headed by University of Nebraska–Lincoln engineering faculty is developing a new barrier material that would make the deep geologic disposal and storage of spent nuclear fuel a much safer proposition.

“Long-term degradation of these types of spent fuel can require they be stored more than 10,000 years,” said Jongwan Eun, assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering. “That’s a surprising time period. And with concerns about the materials that have been used for years, we have to meet this environmental challenge.”

In 2011, the U.S. halted funding for the Yucca Mountain Nuclear Waste Repository in Nevada. This left American utilities and the federal government without a designated long-term storage site for high-level radioactive waste, which takes thousands of years to decay.

“They are piling spent fuel next to the power plants,” Eun said. “There is pressure to develop a permanent solution for radioactive waste sequestration, and the DOE is spending research money to investigate the fuel cycle — generating the material, operating and disposal. Our project is developing a new material for disposal safely and looks to meet the environmental challenge, as well.”

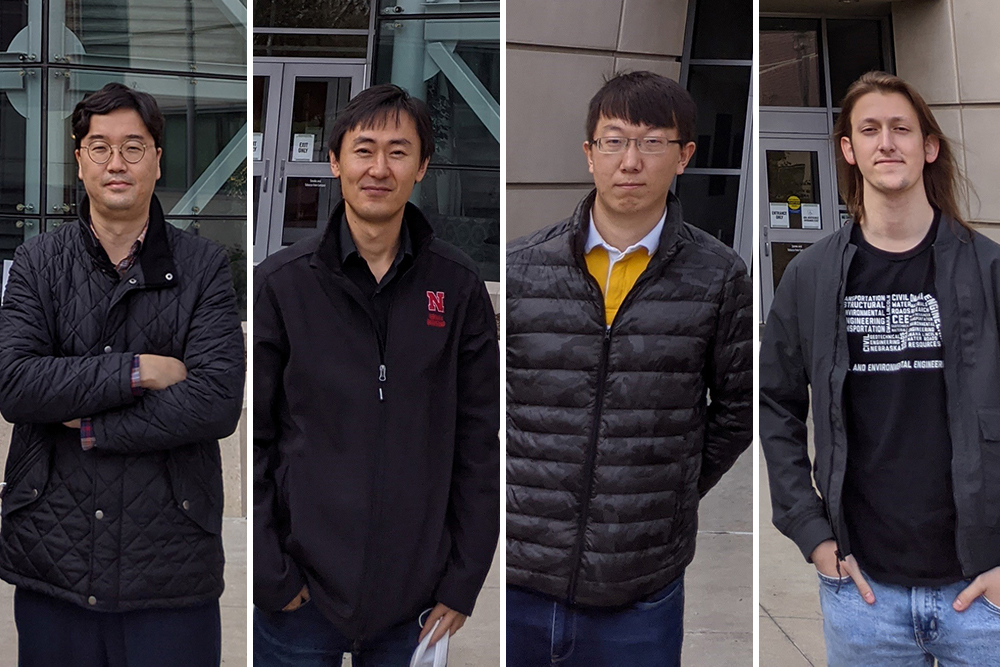

Eun is collaborating on the project with Seunghee Kim, assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering; adjunct faculty member Yong-Rak Kim, who is also a professor of civil and environmental engineering at Texas A&M University; and Sandia National Laboratories.

“We have been working on other energy issues for years, so it was only natural that we look at the issue of geological storage of spent nuclear fuel,” Seunghee Kim said.

Current disposal protocols have stayed the same for decades, including the way the disposal sites are constructed, Eun said. Typically, this requires tunneling deep into the earth and building a bunker to house metal drums filled with the radioactive spent fuel. These bunkers are often encased in layers of soil and harder materials, such as concrete.

Some of these spent fuels are radioactively hot — up to 200 degrees Celsius (about 400 degrees Fahrenheit), Seunghee Kim said. These types of temperatures can create cracks in the materials used to store the nuclear waste.

Thus, the Nebraska team is looking at adding an inorganic microfiber, such as glass, to bentonite to create a less-permeable and more-durable and heat-resistant material to store the spent fuel.

“For other infrastructure projects — like the construction of large buildings or paving roads — we mix inorganic fibers into concrete or soils and give the material mechanical and engineering properties. This is a new idea for a spent-fuel waste disposal facility,” Eun said.

According to https://www.eia.gov, the United States in December 2019 had 58 active nuclear power plants in 29 states, including one in Nebraska — the Cooper Nuclear Station near Brownville. In October 2016, the Omaha Public Power District shut down the Fort Calhoun Nuclear Station north of Omaha. The facility isn’t expected to be fully decommissioned until at least 2058.

In the U.S., spent fuel from nuclear power plants is usually stored thousands of feet underground. One of the major concerns about nuclear waste storage in Nebraska is the leaching of radioactive spent fuel into the massive aquifer that lies below the state’s surface.

“We want to make sure we put something strong and durable between this fuel and Nebraska’s groundwater system,” Seunghee Kim said. “We want to make sure that it will be OK and protect all of us in the future.”