A multinational team of scientists, drillers and engineers has deployed to a remote part of Antarctica on an urgent mission to predict how fast the West Antarctic Ice Sheet will melt from global and ocean warming.

Continuing a 50-year history of leadership in Antarctic science, the University of Nebraska–Lincoln joined about 35 research institutions from 10 nations for the two-year project, called Sensitivity of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet to 2 Degrees Celsius of Warming, or SWAIS2C.

“Our planet is at risk and we need information from the heart of Antarctica, at the vulnerable margins of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, to understand how it will behave in the future as Earth warms,” said David Harwood, who has headed the Antarctic Science Management Office at Nebraska for more than two decades. “Someone from the international team of scientists is studying just about every scientific and geological aspect of the sediment cores.”

The scientists hope their findings will help the world adapt to rising sea levels and encourage efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

“Whatever we recover and discover on this trip will be new to humankind and important in understanding future sea level rise,” said co-chief scientist Richard Levy, a glacial stratigrapher and paleoclimatologist at Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand. Levy is Harwood’s former student and holds a doctorate from Nebraska, just one example of the project’s many Nebraska ties.

During the next two months, the SWAIS2C team will drill up to 200 meters into the sediments beneath the Ross Ice Shelf — one and two-thirds times as deep as the Nebraska State Capitol is tall. The geological samples to be retrieved hold crucial information about ice shelf and ice sheet stability, and their dynamic history of advance and retreat in response to global temperature fluctuations.

Regardless of future global carbon dioxide emissions, team leaders say, faster melting of the ice sheet and a subsequent rise in sea level is unavoidable. The questions now to be answered, with guidance from history of when the ice sheet retreated and marine seas covered West Antarctica, is how far and how fast the ice will melt.

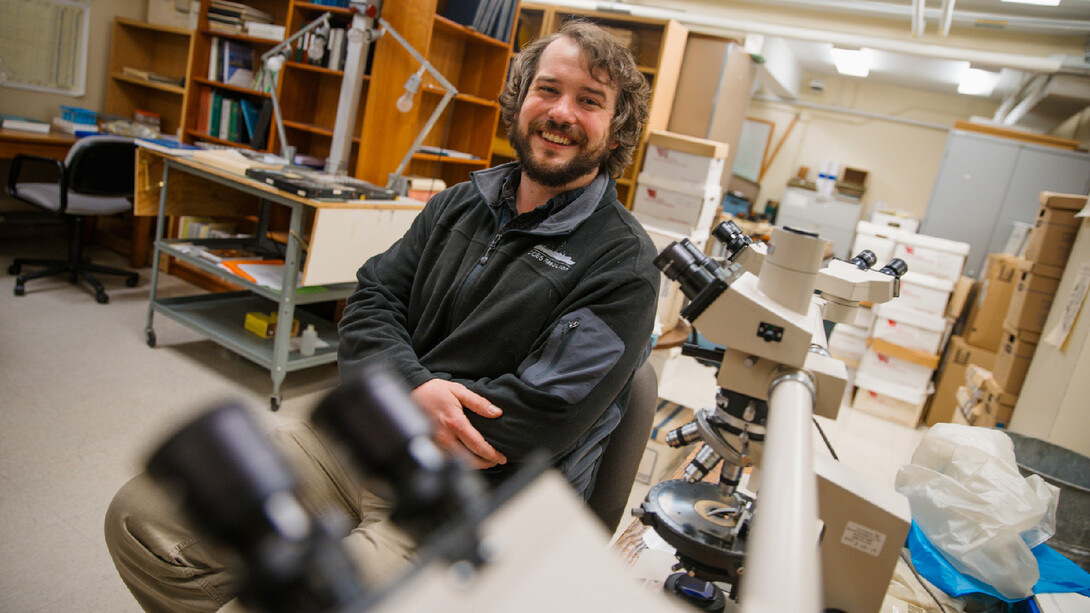

Assisted by postdoctoral researcher Jason Coenen and doctoral student Megan Heins, Harwood will date sediment cores retrieved from drilling operations near where the ice shelf leaves bedrock and begins to float.

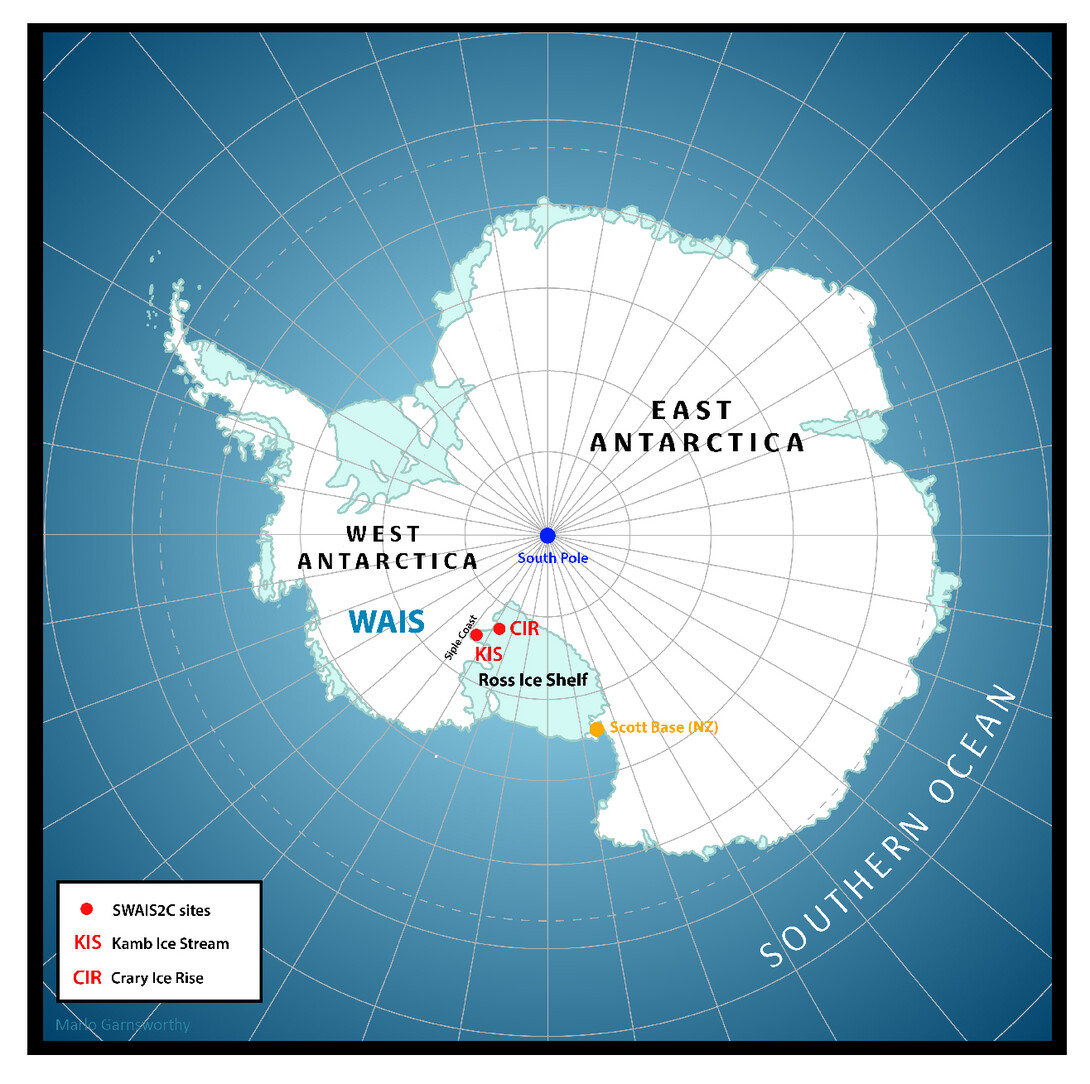

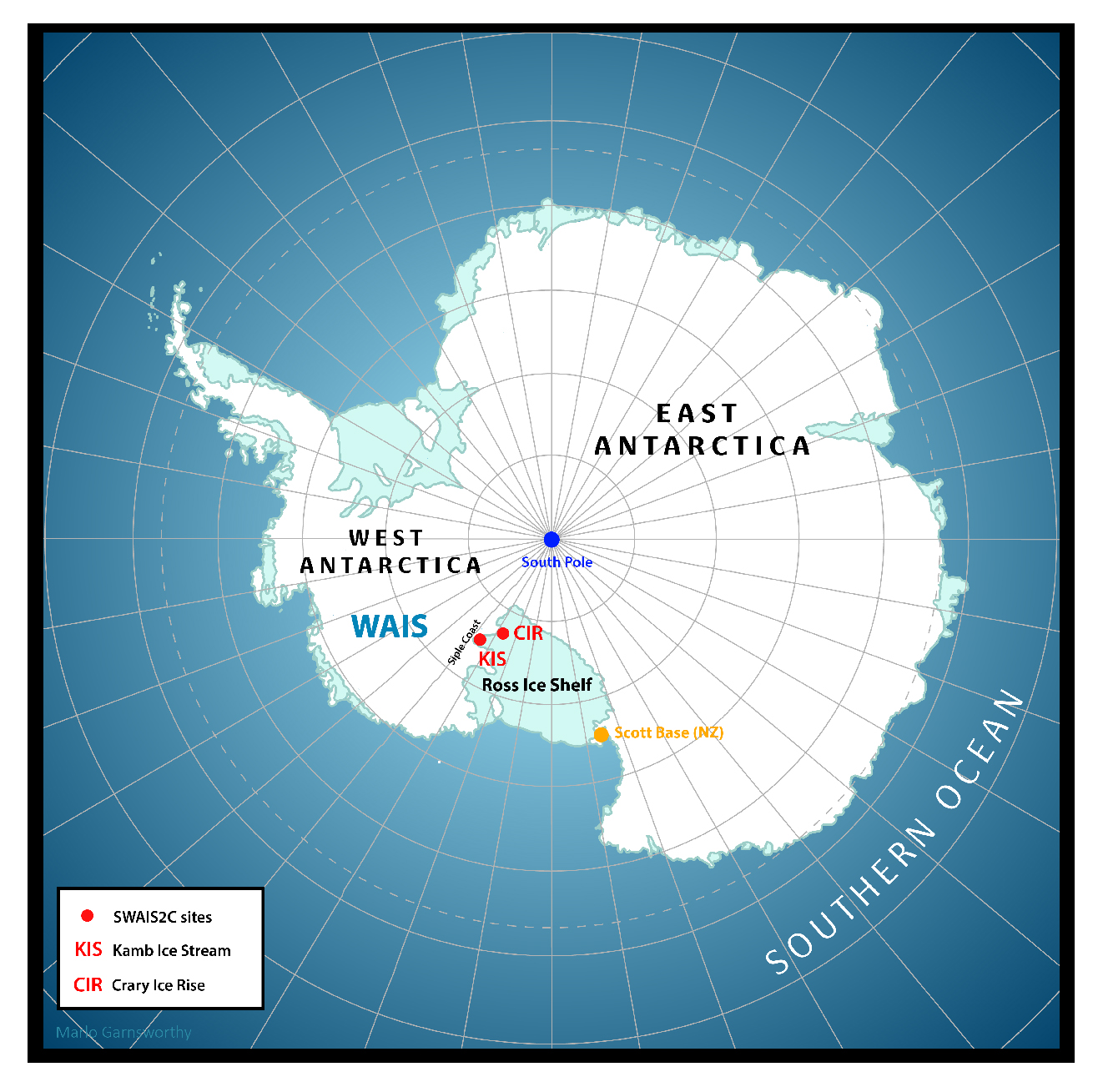

Although Harwood is not traveling to Antarctica this year, Coenen is one of a handful scientists who will work “on ice” at a drill site along the Kamb Ice Stream, located on the southeast margin of the Ross Ice Shelf, about 500 miles from McMurdo Station, the U.S. Antarctic research station near the seaside lip of the ice shelf.

Coenen will serve as a core manager, helping safeguard cores of rock and sediment retrieved for later study by more than 80 scientists worldwide. During and immediately after the fieldwork, he will prepare multiple sets of microscope slides with tiny samples of core material so that he and other scientists can develop preliminary information about the time frames represented by microscopic fossils in the sediment cores.

The sediment cores will be shipped to New Zealand at the end of the drilling season. Members of the Husker fossil team will travel there in April to join a team of international sedimentologists who will work together to characterize the recovered cores. It is a foundational role, because other scientists from around the world will use the data developed to decide which samples to request for their work.

Observations gathered by the worldwide team will be used by other scientists to build numerical models of the ice sheet, the surrounding oceans and the underlying ground to predict changes to the ice sheet and related environment. Scientists from the participating nations of Germany, Australia, Italy, Japan, Spain, South Korea and the Netherlands, along with New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States, will gather for an international workshop in April 2025 in Dunedin, New Zealand, after the second season of drilling.

The first findings from the project could be published as early as 2025.

Participating U.S. institutions, supported by the National Science Foundation’s Office of Polar Programs, are Binghamton University, Central Washington University, Colgate University, Colorado School of Mines, Columbia University, Indiana University-Purdue University-Indianapolis, the University of Massachusetts Amherst, Northern Illinois University, Ohio State University and Nebraska. Co-chief scientist Molly Patterson of Binghamton University is the U.S. lead scientist. Lincoln native Denise Kulhanek, a professor at Kiel University in Germany, also will work at the drill site in December and January.

Coenen is an expert in micropaleontology of diatoms, a photosynthetic algae. Diatom fossils indicate past times when West Antarctic regions were undersea and free of ice. They also can be used to trace how ice streams that flow within the ice sheet have changed directions over the eons.

“One of the goals is to identify oceanic sediments that are less than five million years old, so we can get a sense of how the West Antarctic Ice Sheet responded to past warming scenarios similar to what we have today,” Coenen said.

The mid-Pliocene warming period, about three million years ago, is an important marker, he said, because it was the last time the Earth’s atmospheric carbon dioxide levels resembled today’s, at more than 400 parts per million. Prior drilling and numerical modeling results suggest most of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet was gone.

“The scenario of that retreat is what we’re trying to pinpoint as we move toward this 2-degree Celsius warmer world in the next 50 to 100 years, or sooner,” Coenen said.

In 2024-25, the project will move to Crary Ice Rise, a dome of ice on the Ross Ice Shelf’s southeast margin. Both the Kamb and the Crary sites were chosen because of their location along the Siple Coast, a sensitive and dynamic zone where the West Antarctic Ice Sheet lifts off the seafloor and begins to float.

At present, there are only 13 locations under the West Antarctic Ice Sheet where geological samples have been recovered. The two deepest sampling locations among them, at 1,300 and 1,100 meters deep, were drilled using the ANDRILL rig in 2006 and 2007 projects managed by UNL’s Antarctic Science Management Office.

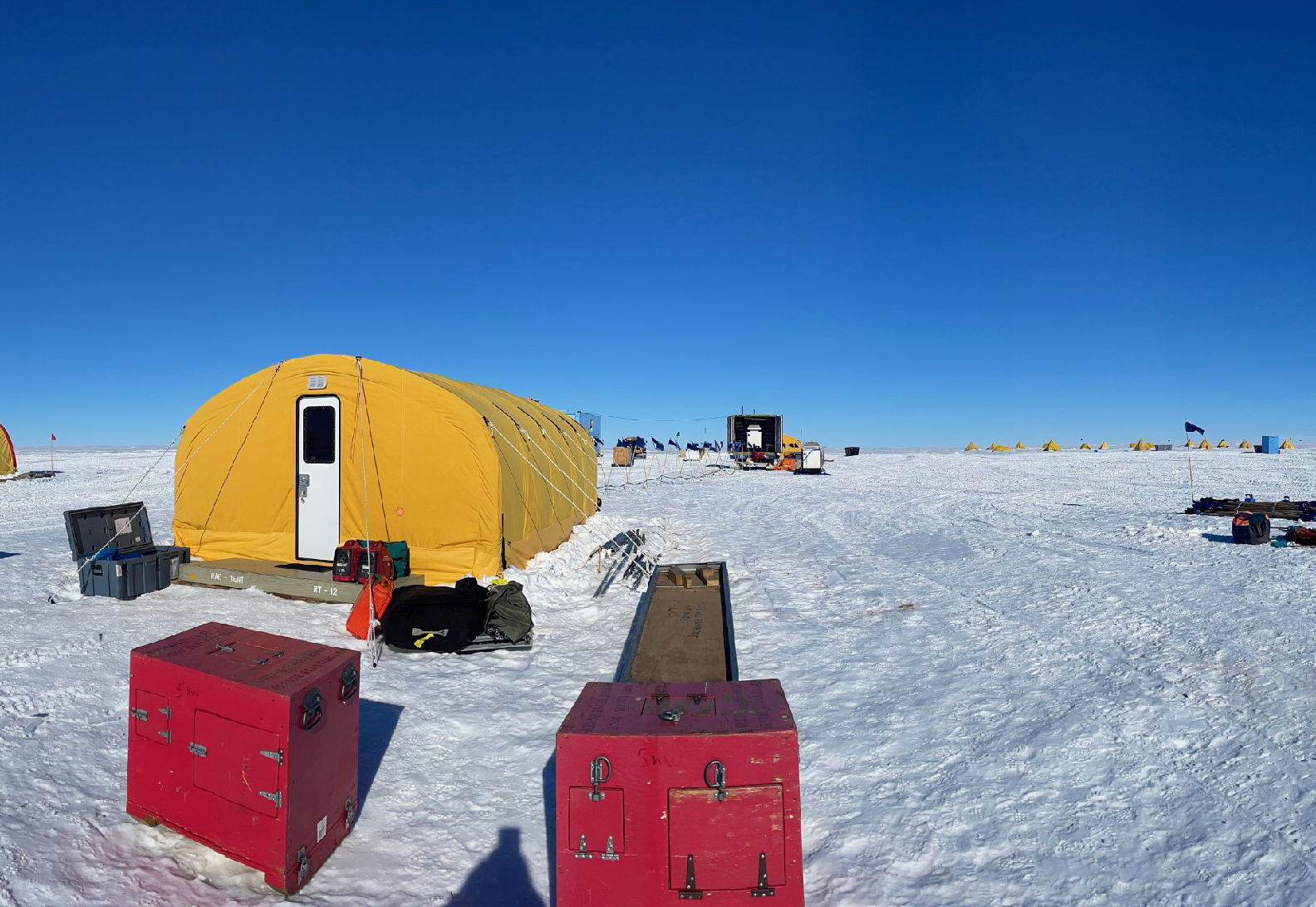

For the SWAIS2C project, New Zealand personnel constructed and are operating a purpose-built drill that is smaller, lighter and more portable.

“Siple Coast is so remote, at the edge of the grounded West Antarctic Ice Sheet, well inland across the Ross Ice Shelf,” Harwood said. “It is hard to get to, and hard to put a drilling system as large as ANDRILL out that far.”

Harwood hopes the ANDRILL rig might be deployed for deeper drilling in the future, as a follow-on to the SWAIS2C project.

Nebraska has been at the forefront of Antarctic science since the early 1970s, when former Antarctic explorer James Zumberge was chancellor. Zumberge, who died in 1992, has two Antarctic land features named in his honor, Cape Zumberge and the Zumberge Coast.

In 1973, UNL began managing the Ross Ice Shelf Project under the direction of Zumberge and Robert Rutford, a faculty member and interim chancellor who later became director of the NSF’s Division of Polar Programs. Rutford died in 2019.

RISP was the first project to melt through the Ross Ice Shelf to study the ice and the ocean and seafloor sediments beneath. In 1974, UNL became the home of the Polar Ice Coring Office, providing logistical support and drilling services to an international cadre of scientists in both Antarctica and Greenland.

The university managed PICO for more than a decade after the Ross Ice Shelf Project ended. James McManis, manager of Nebraska’s Engineering and Science Research Support Facility, was a leader in designing and building various sediment and ice drills for PICO, as well as hot-water drills used for subsequent projects.

Harwood formed the Antarctic Drilling Science Management Office at Nebraska in 2001. He and a Northern Illinois University colleague obtained NSF funding for the ANDRILL rig in 2002. In 2006, Harwood and UNL were awarded a $13 million NSF grant to support U.S. research on science management for the ANDRILL Project and to develop and coordinate an education and outreach program during the International Polar Year in 2007-08.

In 2015, Harwood began managing the use of UNL-designed hot-water drills that were used to bore through the ice shelf to learn more about Whillans Subglacial Lake and Mercer Subglacial Lake — projects that led to the discovery of microbes, viruses and other life forms surviving in the frigid subglacial waters.

Harwood, McManis and Dennis Duling, lead driller on the subglacial lake projects, are working to develop an even more innovative drill, powered by the hot-water pressure, that can core and recover both ice and sediment.

Although it takes leadership and decades-long perseverance to launch such complex international projects, Harwood said he’s gratified that SWAIS2C has attracted a new generation of young scientists.

Among them is Coenen, who previously visited Antarctica for field research in 2014-15 while a graduate student at Northern Illinois University.

“It’s an adventure of a lifetime, being out there in this beautiful wilderness,” Coenen said. “The potential for the science. Working with international colleagues. Even just flying in on the LC-130 (a ski-equipped aircraft) and seeing the ice come slowly into view. When they drop down the door after landing and you have all that white reflective light that’s just shining onto you, it’s like you’ve landed in a completely different world.”

Said Harwood: “It’s very rewarding for an old guy like me, with many years of Antarctic adventures behind me, to see really bright, budding scientists launch into their future doing exciting science that is important for society and humankind.”

Share

News Release Contact(s)

Related Links

Tags

High Resolution Photos

HIGH RESOLUTION PHOTOS

HIGH RESOLUTION PHOTOS

HIGH RESOLUTION PHOTOS