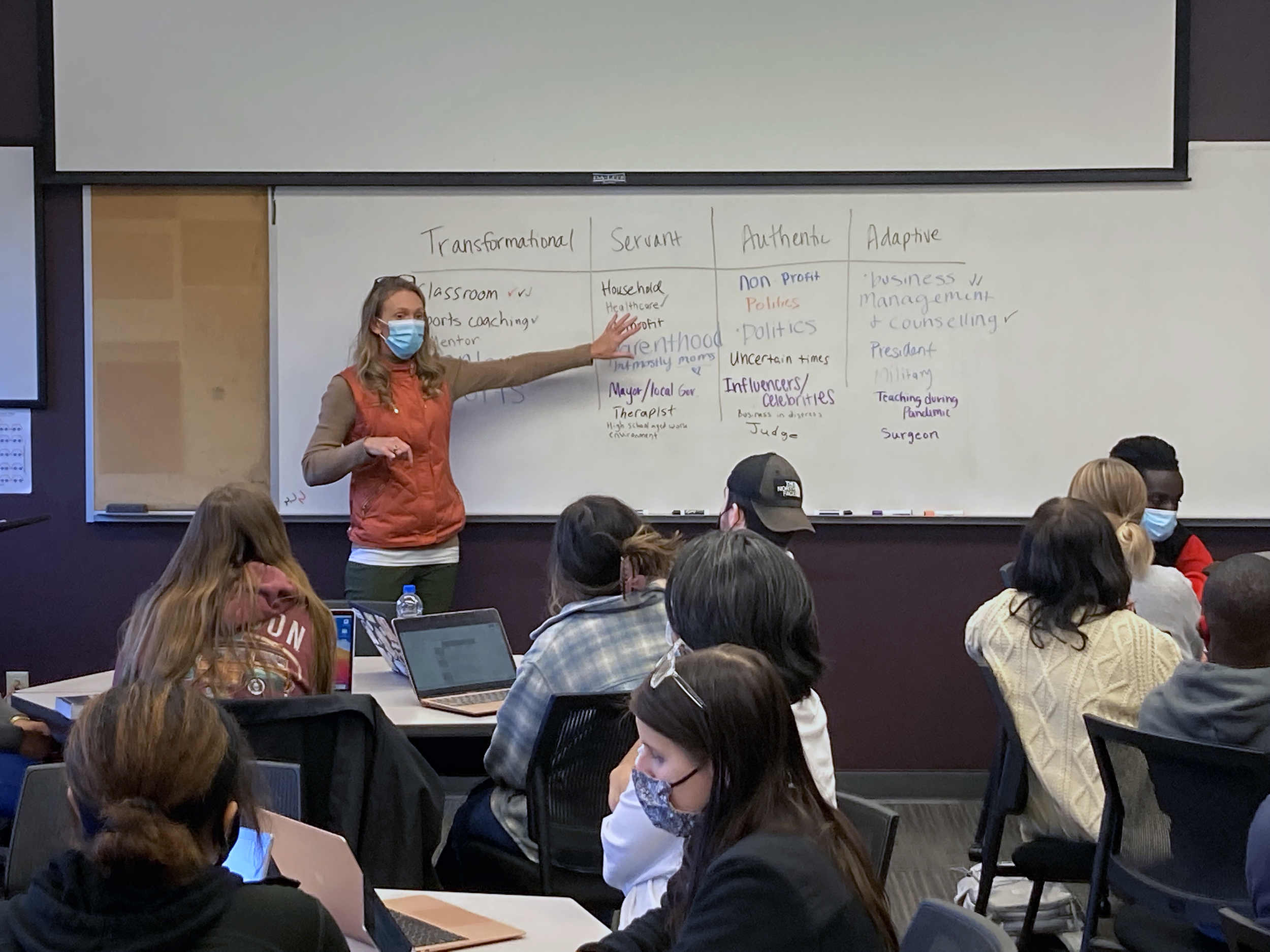

Standing in the front of her classroom, Lindsay Hastings pointed to different leadership styles written on the board. The class was ALEC 202, Foundations of Leadership Theory and Practice. While Hastings and her students discussed how the leadership styles varied, one thread tied them together — a belief that effective leaders inspire hope.

Hastings is a Clifton Professor in mentoring research at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln and research director for the Nebraska Human Resources Institute Leadership Mentoring program. Hope drives much of her scholarship. However, that wasn’t the intent when she began a study of leadership and wealth transfer in 2014.

“The United States is poised to experience one of the largest leadership transfers in its history,” Hastings said. “This is coupled in rural communities with a sizable wealth transfer. Between now and 2060, $75 trillion will be transferred from older generations to the younger.”

These transfers, she said, will “disproportionately impact rural communities.”

This impact prompted Hastings to ask, “How can we help rural communities navigate both wealth and leadership transfers?”

Her mixed-method study began qualitatively, with interviews of youth and adult leaders in Valley and Holt counties, as well as in Nebraska City — all places with a track record of successful leadership transfers. After months of interviews, Hastings and the students working with her tried to discover what set these communities apart.

“In these communities, a small group of leaders did something,” she said. “They passed (an economic development act), started a leadership development program, set up a philanthropic fund — something. And that something spread hope within the community.”

Latching onto that idea, Hastings and her team hypothesized “that belief in community leadership predicted hope, and hope predicted civic engagement,” she said.

The second, quantitative half of the study analyzed community leadership, hope and civic engagement — this time throughout the state, via the Nebraska Rural Poll. The results surprised Hastings. The line from trust in community leadership to civic engagement was negative, meaning the more one trusted their community leaders, the less likely they were to be civically engaged, and vice versa.

“Belief in community leadership, only when mediated through hope, inspired civic engagement,” Hastings said. “That was one of the most fascinating findings of this study.”

“Hope” is defined as “a feeling of expectation and desire for a certain thing to happen.” So how does one measure a feeling? Hastings and her team used data from the Rural Poll, such as how respondents answered the questions, “I believe my community is better today than it was a year ago, five years ago, 10 years ago.”

“Hope is a mindset,” Hastings said. “If we believe our community’s in a better place than it was, what can we point to, to say, ‘This is why our community is better?’ Then we can see that if we want our community to be in a better place, there’s a way to get there. Not every initiative is going to work, but we’re going to try. In other words, we’re going to hope.”

Published in the academic journal Community Development with co-authors Hannah Sunderman, Matthew Hastings, L.J. McElravy and Melissa Lusk, the study has two takeaways.

“First,” Hastings said, “we should not take this notion of wealth and leadership transfer lightly, nor should we sit back to wait and see what happens. If we can be intentional and strategic in managing those transfers well, they can be a driving force for vitality.

“Second, never underestimate the power of what a small group of people can do. Even in communities that don’t have a 20-year history of community development, a small group of people who are willing to put in a little sweat equity can do a lot, just through hope.”

Hastings’ future scholarship interests focus on hope trajectories. Looking at a 25-year history of hope-centered questions from the Rural Poll across economically and demographically matched Nebraska communities, Hastings is interested in exploring what factors create and increase (or decrease) hope within a rural community.

“Thriving communities aren’t an accident,” she said. “The more we’re intentional, even if we start small about communicating hope, the more those smalls steps can turn into big needle moves.”

To learn more about Hastings and her work, click here.

To learn more about the Rural Poll, click here.