The sweeping prairies of the Great Plains are shrinking by millions of acres every year under the combined pressure of cropland conversion and rapid spread of invasive trees.

Scientists and conservationists have said Great Plains grasslands are among the world’s most threatened ecosystems. Collapse of the biome would bring serious consequences for livestock production, wildlife habitat, water security and wildfire management. Schools and communities also lose revenue when rangeland production is lost to woody invasions on lands where profits go to fund public education.

Highlighting the importance of grassland conservation in federal agriculture policy, Terry Cosby, Natural Resources Conservation Service chief, recently met with Dirac Twidwell, professor of agronomy and horticulture at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, and Derek McLean, dean of the Agricultural Research Division at Nebraska, along with Robert Lawson, Nebraska NRCS state conservationist and other partners.

Cosby was briefed on increasingly successful efforts to put the latest conservation research into the hands of private landowners seeking to save their piece of the prairie. Like much of the Great Plains, 97% of Nebraska is privately owned and nearly half of the state is productive grassland that is losing ground to land-use conversion and invasive trees.

Lawson invited Cosby to see Nine-Mile Prairie and neighboring properties while the chief visited Lincoln for the opening of a newly constructed USDA facility near the State Capitol.

“Through a unique agreement with UNL’s Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources, the Natural Resources Conservation Service and our conservation partners have redoubled efforts to preserve our grasslands in Nebraska and other Great Plains states and improve public understanding of serious threats such as woody encroachment,” Lawson said.

The agreement established Twidwell as a science adviser for the NRCS, speeding up the adoption of new science and technology while improving desired outcomes of grassland conservation investments.

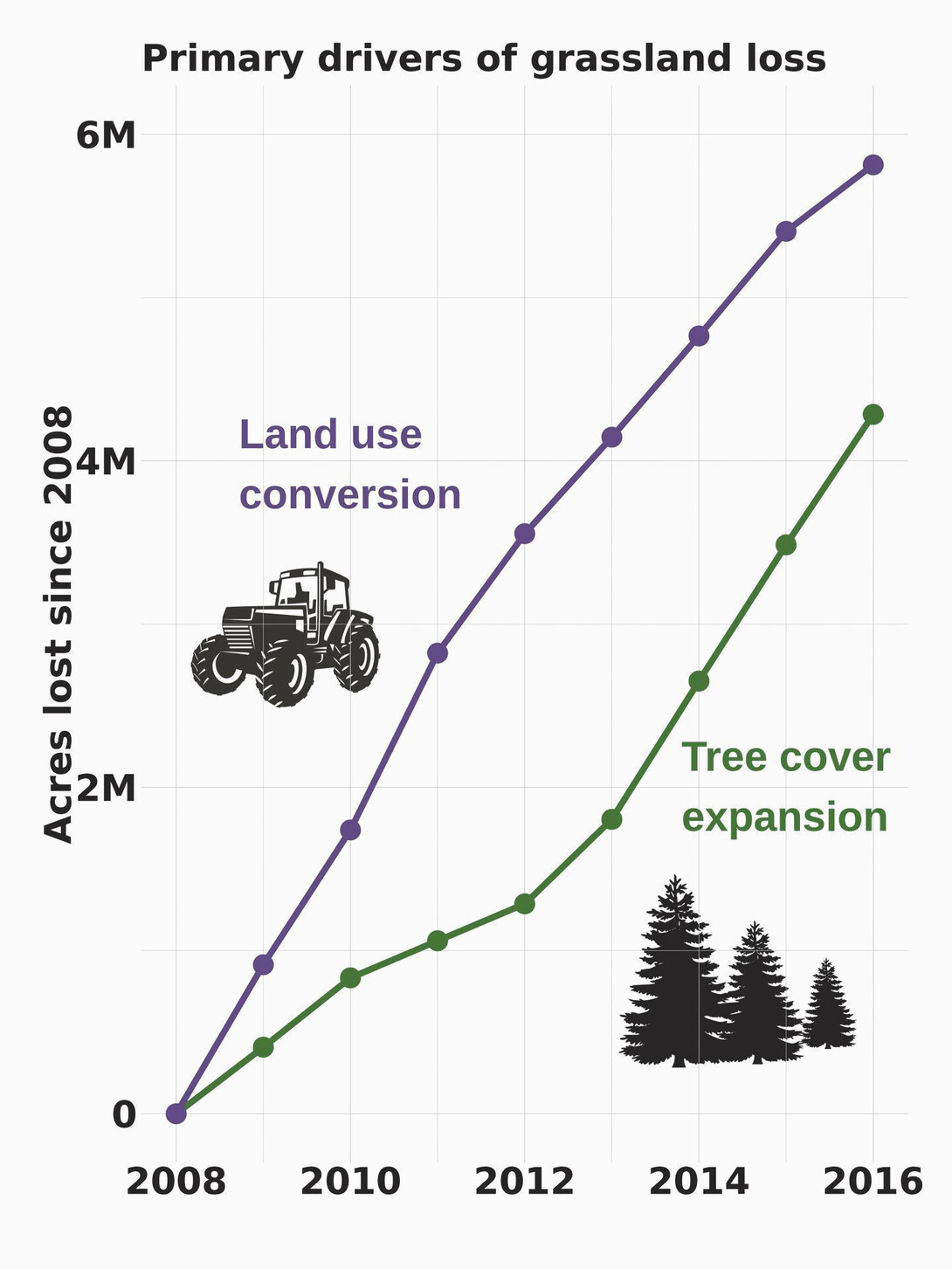

“Most people know that land-use conversion was one of the top drivers of grassland loss last century,” Twidwell said. “In recent decades, woody encroachment has emerged as the other primary driver of grassland loss in the Great Plains and actually converts as much grassland every year as row crop conversion.”

Seemingly minor shifts in vegetation can quickly disrupt the function of a grassland ecosystem. For example, prairie-chickens will avoid otherwise suitable grasslands at just two trees per acre and will stop breeding altogether as tree infestations continue. Forage production declines by 75% as grasses are replaced by bare ground under trees.

In 2021, the NRCS helped launch new Great Plains Grasslands Initiatives in Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska and South Dakota. The same year, Twidwell worked with NRCS Working Lands for Wildlife to help develop NRCS’ first-ever biome framework for grassland conservation, which reinforces efforts to address biome threats of land use conversion and woody invasions.

NRCS state conservationists from the partner states agreed that a more proactive strategy was needed if the central Great Plains was to halt the history of grassland loss to woody invasions. The agreement with UNL has been extended to continue at least until 2025, with discussions underway for another multi-year extension. The NRCS allocated more than $600,000 to provide scientific support for ramping up conservation efforts, including mapping innovations, technical skills, measurement and reporting, and communicating outcomes.

High-tech tools, such as the Rangelands Analysis Platform, were used to help conservationists and landowners understand landscape vegetation trends at geographic scales ranging from their pasture or ranch to continent wide.

New strategies were also developed from landowner-science partnerships, resulting in a 40-page vulnerability and risk guide about woody encroachment in the region and a pocket guide for planning designed to be used in field training and engagement sessions. More than 50,000 copies have been printed and delivered at the request of conservation organizations throughout the region.

“We were gratified by the chief’s interest in our work here and the collaboration between IANR and the state NRCS office,” said McLean, dean of UNL’s Agricultural Research Division. “Together, we are committed to our pursuit of building research-based strategies that can be used throughout Great Plains states to preserve this vital grassland resource.”

The NRCS chief’s visit also showcased the important training and engagement role played by Nine-Mile Prairie and the other remnants of tallgrass prairie in eastern Nebraska.

University scientists and students have studied Nine-Mile Prairie for over a century, and collaboration with NRCS partners goes back over 30 years. Increasingly, Nine-Mile Prairie is used to provide students hands-on experience, including seeding native plants, prescribed burning and woody species control.

“Nine-Mile Prairie has a storied history,” said David Wedin, professor of natural resources and director of UNL’s Center for Grassland Studies. “NRCS Chief Cosby’s visit is another example of how university sites can serve to engage national, state and local leaders and improve our understanding of the issues facing prairie conservation.”

Lawson touted the preventative approach that Twidwell and his colleagues developed.

“We have reoriented our approach with new science to focus our efforts to prevent woody encroachment within our intact grasslands, while previous efforts focused only on areas already overtaken with woody growth. Waiting to act causes control costs to become much higher for producers,” Lawson said.

During September and October, NRCS and UNL jointly hosted trainings throughout Nebraska for nearly 200 field office staff on the latest best practices on how to better address woody encroachment, based on the latest research from Twidwell’s program.

“Temperate grasslands are recognized in the scientific literature as being the most underappreciated, undervalued and underfunded of the world’s biomes,” Twidwell said. “They have lost more than any other biome, and we are seeing the collapse of the Great Plains grassland biome in our lifetime.”

However, Twidwell sees encouraging signs that the “green tide” can be turned.

“We are on the verge of an unprecedented movement to conserve the last grassland regions in North America,” he said. “Here at UNL, we are going to continue to relentlessly work to support the needs of ranchers and those in the grassland conservation community to better address the drivers of grassland loss.”