EDITOR’S NOTE — As the nation pauses to honor the legacy of President George H.W. Bush, Nebraska Today is looking back at the 41st president’s impact on the University of Nebraska–Lincoln. In this story, we remember Mikhail Gorbachev’s March 14, 2002, appearance on campus and the former Soviet Union president’s influence on Bush’s foreign policy as the U.S.S.R. crumbled and fell. See complete coverage of Nebraska Today’s Remembering 41 series.

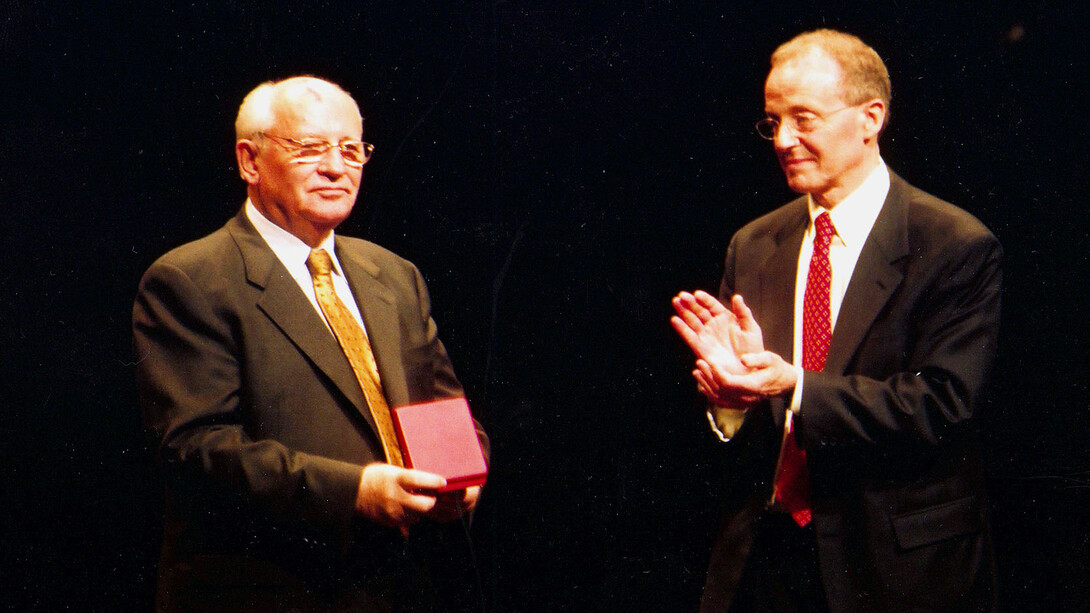

Former Soviet Union President Mikhail Gorbachev told a joke on himself when he spoke at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln’s E.N. Thompson Forum on World Issues in 2002.

Gorbachev had decided in the mid-1980s to limit the sale of vodka to increase Soviet Union productivity.

In his joke, Gorbachev told of three men waiting in line to buy vodka. One becomes exasperated and leaves, saying he would go to the Kremlin to assassinate Gorbachev. The man later rejoins his friends to wait for vodka. “The line was even longer over there,” he told them.

David Forsythe, political science professor emeritus and an expert in international human rights and foreign policy, was among those in the audience for Gorbachev’s March 2002 speech in Lincoln.

Admitting that he has stolen Gorbachev’s joke for his own speeches, Forsythe and other university political scientists and historians reminisced about Gorbachev’s Lincoln appearance while reflecting on the late President George H.W. Bush’s role in transitioning the world out of the Cold War.

“When Gorbachev came in 2002, a decade after the Soviet Union collapse, he reflected on that crucial time,” said Patrice McMahon, professor of political science. “And President Bush was key to making sure that crucial time didn’t become explosive.”

“He gave credit to Bush here in Lincoln — we were so lucky that we had a president who understood the implications of American power and what might happen if American power overplayed its hand. He wasn’t just thinking about the U.S. — he was thinking about world stability.”

National media coverage since Bush’s death on Nov. 30 has made little mention that Bush and James Baker, secretary of state, actually worked to keep Gorbachev — and the Soviet Union — in power.

Tyler White, an assistant professor of practice in political science, also attended Gorbachev’s speech in Lincoln.

“It’s one of the things I remember most about my undergraduate experience, being able to see him and hear from him,” White said. “I don’t think Gorbachev ever really gets enough credit for the way the Cold War ended. And the other person whom I don’t think gets enough credit is George H.W. Bush.”

Although efforts to preserve the Soviet Union failed, White credits the 41st president and his foreign policy team for avoiding a confrontation between the Soviet Union and the West.

“The really key thing, I think, is that Gorbachev never had to go down the path of confronting the West as the Soviet Union was collapsing,” White said. “The one thing we really worry about with nuclear-armed states is that if they start to collapse, they might attack in order to try to stave off the inevitable.”

Bush’s foreign policy team did an “amazing job” of assuring the Russians that the United States wouldn’t exploit the Soviet Union’s weakness, White said. “The assurances given to the Russians and the new states that formed after the Soviet Union fell apart was a master stroke of the Bush foreign policy.”

“Bush didn’t call for the breakup of the Soviet Union, although he welcomed the end of Soviet dominance in Central and Eastern Europe,” said Lloyd Ambrosius, professor emeritus of history. “He sought the peaceful ending of the Soviet empire and the unification of Germany, but not the collapse of the Soviet Union itself.”

“What’s useful to remember is that Bush came of age and worked in politics entirely during the Cold War,” said Tim Borstelmann, professor of history. “He understood the Soviet Union and was not clear about what would replace the Soviet Union should it come apart. That thought would have been quite unnerving to someone as cautious and prudent as Bush.”

Bush and Baker liked Gorbachev — who was widely admired in the United States as a defender of freedom — and believed they could form a fruitful international partnership with him.

“They were inclined to go slow on Gorbachev,” Borstelmann said. “Gorbachev wasn’t trying to abolish the Soviet Union, he was trying to reform it with glasnost and perestroika, openness and reform. Bush inherited this situation from Reagan. He was trying to ride the tiger.”

But Gorbachev remained unpopular in Russia, associated with economic distress and other changes that have had a negative impact on the lifestyles of typical Russians.

“Bush and Baker thought so highly of Gorbachev, they wanted him to continue in office,” Forsythe said. “Instead, we got an independent Russia with (Boris) Yeltsin at the head and all of that eventually led to (Vladimir) Putin. Bush wanted history to go in a different direction. He tried and it just didn’t work.”

Forsythe said it was consistent with Bush’s cautious and prudent nature to prefer Gorbachev and the structure of the Soviet Union. In his memoirs, Bush wrote that he wanted to see “stable, and above all peaceful, change… the key to this would be a politically strong Gorbachev and an effectively working central structure.”

“Bush and Baker thought they had a reliable partner in Gorbachev,” Forsythe said. “They knew Gorbachev and they knew the Soviet Union. They didn’t know what they were getting with Yeltsin and the new Russia.”

In August 1991, Bush delivered what was is now called the “Chicken Kiev” speech in the Ukraine, in which he cautioned against “suicidal nationalism’” and urged the Ukraine to remain part of the Soviet Union. By the end of that year, Gorbachev had resigned and the Soviet Union was no more.