A fungi expert at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln has helped define the funk behind Nebraska’s first all-homegrown craft beer.

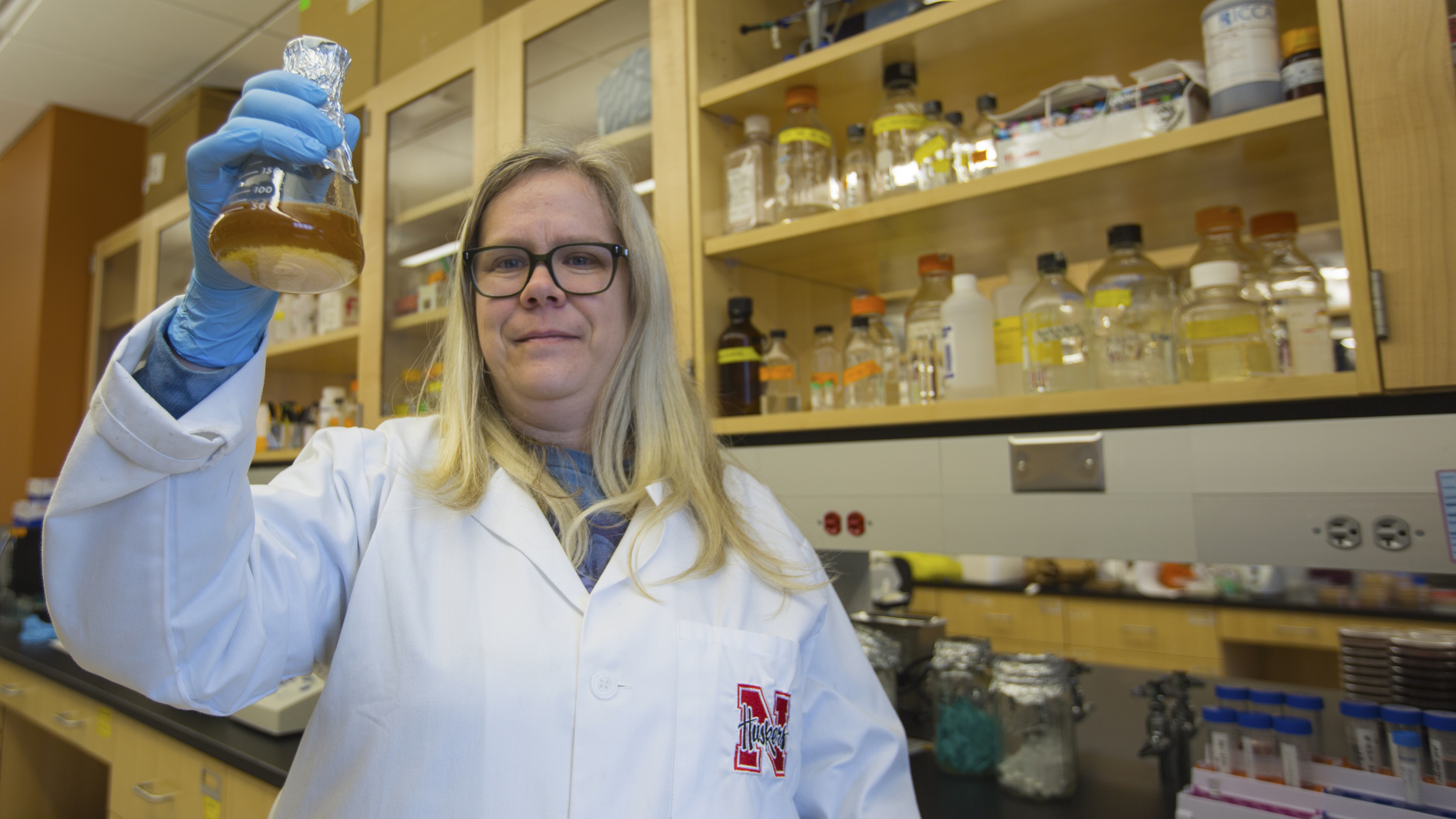

While preparing a presentation for an early January brewing conference at Nebraska Innovation Campus, Heather Hallen-Adams, an assistant professor of practice in food science and technology, issued a call for Nebraska brewers to submit yeast samples for scientific identification.

“The topic of my presentation had to do with obtaining, maintaining and characterizing yeasts,” Hallen-Adams said. “I thought it would be more fun discussing actual samples from the brewers instead of me telling them information available in any book about yeasts.”

>>> Brewing equipment added to Nebraska’s Food Innovation Center

Among the simplest of higher organisms, yeasts are readily available. In brewing, yeasts power fermentation, converting sugars in wort — a liquid base of beer “tea” created by boiling grains and hops in water — to alcohol and carbon dioxide. They are often described as a brewers’ most secret, sometimes proprietary, ingredient.

“Having the chance to learn about yeasts we’ve been using or considering from an expert like Heather was just a very cool opportunity,” said Tim Thomssen, brewmaster at Lincoln’s Boiler Brewing Company. “It also came at a serendipitous time as we had this one variety that we knew produced great beer and wanted to know more about.”

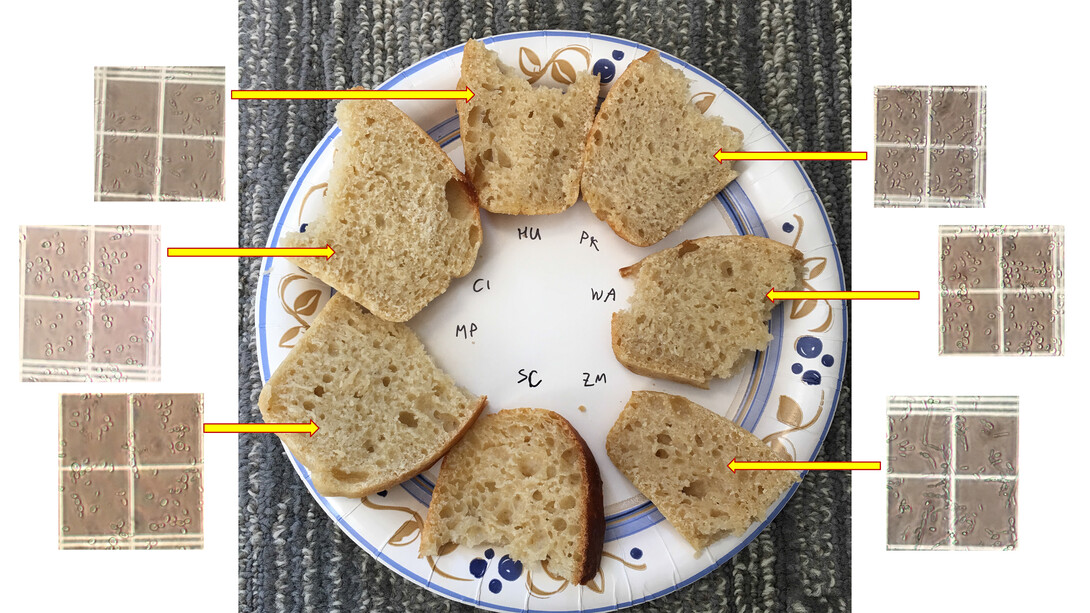

Boiler, which provided two yeast samples, was one of five breweries to participate in the project.

Delving into the DNA and characteristics of the samples, Hallen-Adams found that one from Boiler was not viable for brewing. The other sample, which was discovered by accident and featured in Boiler’s new Nebraska Native, the first commercially available craft beer made only from Nebraska ingredients, displayed favorable characteristics.

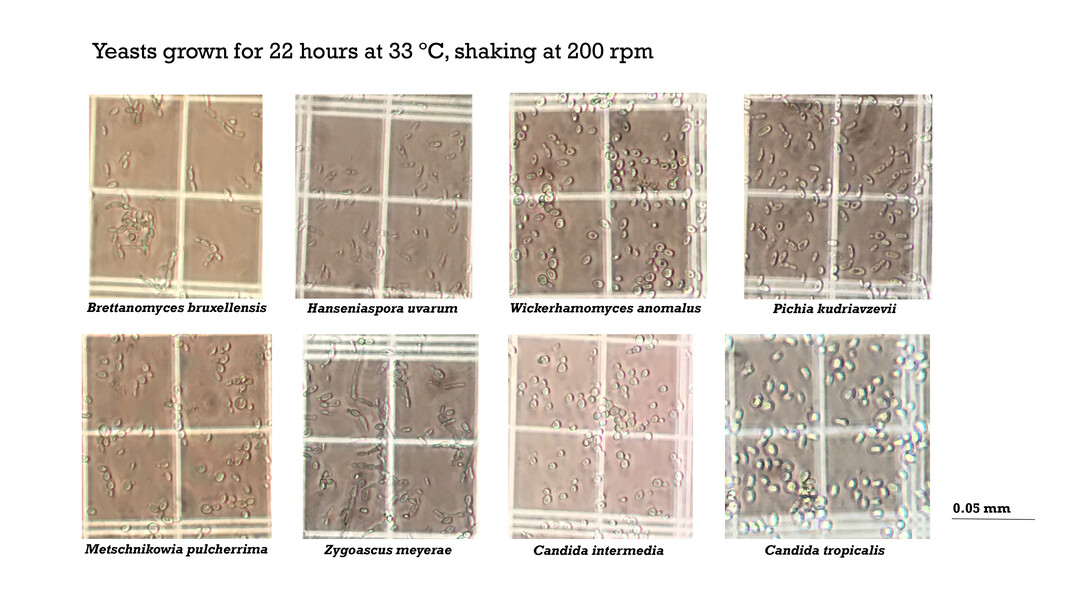

“It’s a fairly common yeast, but it has a little more interesting morphology than standard brewer’s yeast,” Hallen-Adams said. “It grows at a much slower rate and utilizes almost any sugar it will encounter in the fermenting process. Those tendencies make this an efficient and valuable yeast for brewing.”

Through her work, Hallen-Adams identified the yeast as Brettanomyces bruxellensis, a strain associated with Belgian beer styles, including lambics, Flanders red ale, gueze, Kriek and Orval.

“Brewing is a kind of backyard science where we learn through the practical application of the process,” Thomssen said. “We suspected this was Brettanomyces bruxellensis based on the flavor profile in the beer.

“But it was great to have Heather confirm it through DNA sequencing and provide detailed information on the conditions it likes to operate in.”

While it was first classified in 1904 in Belgium, the yeast is Nebraska-based and was discovered after a Lincoln Lagers Homebrew Club event five years ago.

Thomssen said the club was conducting a yeast experiment and brewing outdoors near an apple orchard. Dividing a batch of wort, the members each added a different strain of yeast to produce unique beers.

Some of the chillers used to cool the wort failed and members removed bucket tops to speed the process. Weeks later, when the club sampled the beers, one that should have presented like a malty English ale tasted like a funky, earthy Belgian brew.

“A friend who is a beer judge at the national level and a cicerone tasted it and said it was special,” Thomssen said. “So, Aaron Carnes, a microbiologist friend of mine, isolated the wild yeast and we stored it in a freezer at minus-80 degrees for the last five years. And now it’s in our all-Nebraska beer.”

Hallen-Adams was able to narrow down the source of the yeast to the nearby apple orchard.

“It made sense because there were apple guts all around the area,” Thomssen said. “We figure it must have blown in when the tops were removed to cool the wort. It was a pleasant accident.”

Hallen-Adams is part of Nebraska’s gut function initiative and studies fungi that live in the human digestive system. She is a mycologist (fungi biologist) and often consults with Nebraska Poison Control on mushroom poisoning incidents.

“I find gastro-intestinal microbiology to be amazing and challenging, but the work with the breweries has been very interesting,” Hallen-Adams said. “It’s a growing industry in Nebraska and I hope we can continue to develop the relationship between the breweries and the university.”